Toby Unwin Of ‘Premonition’: Mining Legal Data For More Effective Counsel Selection

Toby Unwin Of ‘Premonition’: Mining Legal Data For More Effective Counsel Selection

David J. Parnell

Contributor

The credence nature of legal services has made “highly effective” legal consumption a notoriously difficult task. But the continually evolving major legal consumer is creating a much savvier, and therefore, more practical and scrutinizing evaluation process. While interpersonal skills and the quality of the relationship between parties are still important factors in the purchasing equation, legal consumers are increasingly able to make decisions based on practical utility as well.

A major component in this algorithm is access to evaluative information. League tables can inform you about a law firm’s activity. Third party rankings can inform you about market feedback. Word of mouth can inform you on subjective firsthand experiences. But until recently there hasn’t been much available to consumers regarding actual win/lose rates – at least not without an immense investment of time and resources. And while deal work doesn’t (usually) have a “winner” and “loser,” court-bound litigation does.

Seeking to fill this gap is Premonition, a legal analytics company that deploys data mining and analysis to determine individual lawyer win rates before judges. Today we hear from Toby Unwin, Premonition’s chief innovation officer, on, among other things, Big Data, legal analytics, the evolution of the legal market, and some of the more interesting things they’ve found through their data analyses. See our exchange below:

On The Effects Of Big Data On The Legal Profession

Parnell: In what ways do you see Big Data changing the way that law is going to be practiced over the next 10 years?

Unwin: I see that Big Data will bring transparency to law. At the moment, hiring a law firm is an opaque process: You ask around for recommendations, read some “top lawyer” lists, hire a brand name firm, and hope for the best. Sometimes you get it, but often you don’t. Big Data has been used for a few years to analyze legal invoices and dispute some of the more adventurous charges. Aggregating this data will show what firms are charging for certain types of work and make a more efficient market. The really big change, though, will come when consumers understand that you hire the lawyer, not the firm. Individual performance within firms varies hugely. Analytics lets you look deep inside a firm to only select the very best performers from within in. We’re already seeing interest from corporate general counsel to pick panels from within firms, rather than blindly accepting whatever attorney is “sitting on the bench.”

On Law Firms Accommodating The Data-Induced Shifts

Parnell: How do you think that law firms will shift to accommodate these changes? Or put another way, what will law firms look like in another 10-15 years?

Unwin: We have clients that are already using data to highlight their litigation win rates versus their competitors. My fear is that law firms in general will not be able to adapt to the change. Historically, restrictive practices put in place by state bar associations have kept firms safe from competition. For example, the lack of reciprocity of the Florida Bar was put in place specifically to deter New York attorneys from retiring and practicing there. Clients will get picky about which litigators within a firm they’ll hire and how much they‘ll pay. It will be hard to shed expensive, underperforming partners because they’re owners of the firm. The next 6-10 years could well look like episodes of Suits at many firms, where the partners spend more time on corporate politics than business.

Given that the average law partner’s shares are worth a tiny 0.5 PE, there is little incentive to stay and bail out a sinking ship. The best performers will tire of seeing their earning potential diluted by mediocre colleagues and will leave to go solo, or join small groups of other top performers. Expensive non-litigation law is sold by the aura of the firm being a litigation colossus. Big firms will be unable to survive without this engine.

The biggest overhead of any law firm are people and real estate. Semi-virtual law firms in less restrictive jurisdictions, like D.C.-based Potomac Law, will be far more agile and adaptable to a changing market. Technology already allows lawyers to work from anywhere, yet most firms are saddled with large, expensive downtown offices. Firms have to pay employees whether they are billing or not, so there is a huge incentive to keep them billing. Clients don’t like this because it makes for lengthy, expensive litigation. Firms need to keep a “big bench” of lawyers on payroll because corporate customers don’t like to choose firms with less than 100 attorneys. This adds to everyone’s costs. The future of law is 1,000 folding chairs, not a big bench. Semi-virtual firms that lease attorneys or hire local counsel on an as-needed basis will undercut those with big overheads while providing superior win rates. Uber is coming to law.

Photo credit: Eddie Barandiaran

On How Premonition Is Leveraging Data

Parnell: Talk to me about how your company is using data to add to the evolving environment.

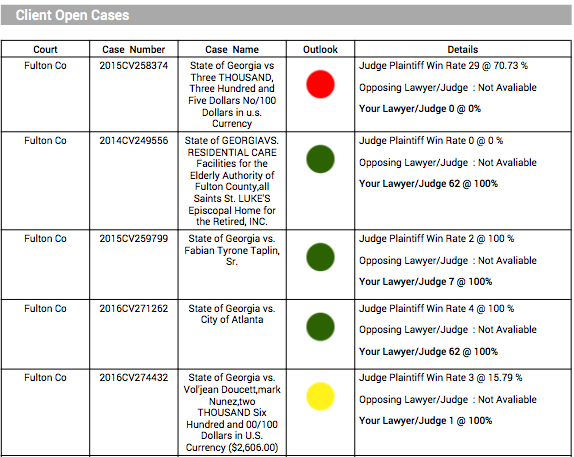

Unwin: We asked a very obvious question: how often do attorneys win? Premonition is an artificial intelligence system that mines Big Data to find out which attorneys usually win before which judges. It is a very, very unfair advantage in litigation. By comparing data from courthouses around the world, we have assembled the world’s largest database of lawsuits.

Outside of the federal system, there is no way to search across the Country. You can search across some States like New Jersey and Connecticut, but this is not the norm. A bad guy in Miami will not appear on a search run in Orlando, for example. We’re seeing a lot of interest from securities agencies and background checking companies as the ability to search nationwide, and even internationally, is vital. Madoff had a string of civil litigation cases before he was uncovered. This happened because people were simply unaware of it. Clients using our vigil system can know instantly and be notified by alerts when cases involving persons of interest are filed.

Probably the most interesting thing we currently do is attorney win rates. This is still a controversial area, despite being blindingly obvious. We have found that the judge-attorney relationship is worth an average 30.7% of the outcome. Judges are human and it is not unreasonable that they view some litigators who appear before them, often, as more credible than others. If the judge crosses his arms when your lawyer starts to speak, this is not a good sign…

By crunching tens of thousands of cases we can pick out these pairings with surprising clarity. Front runners for certain case types per judge are often massive out-performers. For example, when looking for an insurance defense specialist in Reno, NV, we found that the top performer was actually a criminal law specialist who operated from a strip mall on the edge of town. He had 22 straight wins vs. 7 for the runner up. It was like something from Better Call Saul. We showed our findings to a general counsel who told us, “We would never, ever, hire someone like this. But, after seeing these numbers, there is no way we could afford not to.” Even a small shift in results for a major employer or insurance company is worth millions. These are things you would never know without Big Data.

On Artificial Intelligence (AI)

Parnell: Your website mentions artificial intelligence as part of your offering. Can you explain what that means? How are you using AI?

Unwin: Artificial Intelligence is simply a computer making a decision based on an algorithm. A human simply can’t handle reviewing the 41,000 civil cases that are filed in America each day. Humans get lazy, tired, and inattentive. We have biases and often believe we are hugely better at something than we actually are. For example, none of the things we traditionally judge attorney performance by – like law firm or law school – have any correlation with actual success. The best performers often surprise you and are usually overlooked.

Premonition is currently a “narrow AI” system; this means it’s good in very small niches. It’s not “general AI” like the Terminator; it has no ability to drive a car, learn the violin, or play computer games like other expert systems. It can read law cases to determine winners with frightening speed and knows more about judges than their clerks, but is completely incapable of doing anything else unless we teach it.

People view Premonition as a law business. That’s not strictly true. Premonition is a perception/reality arbitrage business. Law happens to be a business where there are huge gaps between what people believe to be good and what actually is. It’s a $400B market where we are the only player to know the value of the goods. We see huge opportunities in arbitraging this knowledge. Law is our first product, but our algorithms also have huge potential in areas like lobbying, healthcare, and education.

On Trends And Points They’ve Uncovered In Their Analyses

Parnell: What are some of the more interesting things you’ve found?

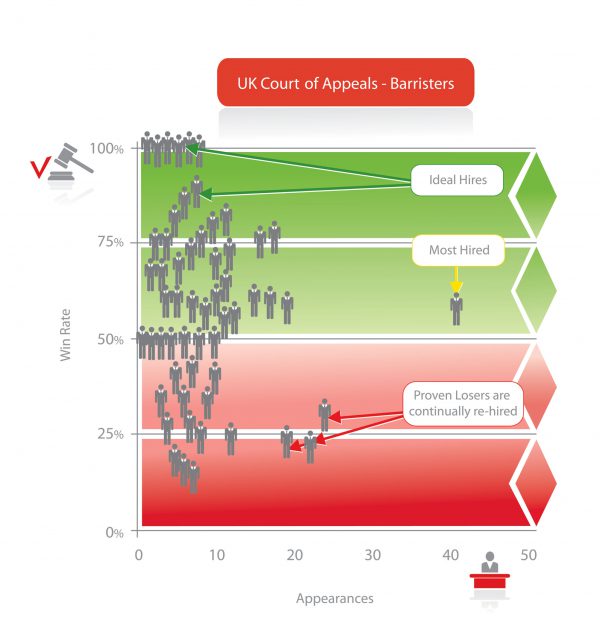

Unwin: We find great lawyers daily. People like Alvin Benton, an associate at Holland & Knight who racked up 32 straight wins before Hon. Margaret Schreiber in the Florida 9th Circuit. These were timeshare foreclosures, a pretty easy case type, but his 97% overall win rate trounced the 75% industry standard. Quite simply, he’s a very, very good lawyer. You may wonder why a lawyer that good is not a partner. Lawyers make partner based mainly on their billing, and we’ve found that how much a lawyer charges has little bearing on their ability. We did a study that found partners were only 1.4% better than associates. So you’re paying significantly more for only a small average increase in performance. You need to pick by the person, not the title.

BigLaw is usually better than boutique. The larger firms have a 6.98% performance advantage. Having said that, a top 20 performer for each judge is only 7.7% likely to be from a big firm. There are many judges who don’t have any BigLaw litigators in their top 20. Picking simply by top 20 per case type and judge gives you an average 80.7% win rate at $358 per hour, vs. 53.49% at $727.00 for BigLaw. In law, you usually don’t get what you pay for.

On The Future Impact On The Individual Attorney

Parnell: What does this mean – in your opinion – for the average BigLaw partner?

Unwin: It depends hugely on the individual. BigLaw will move to a more virtual model. The good news is that law firm shares have relatively little value and less restricted companies, like Axiom, are highly valued by the market. The old saying that lawyers “live rich and die poor” – due to high billing, but low equity value – will no longer hold true for those that adapt and do so early. Poor performers and those that cling to antiquated corporate structures will encounter huge challenges as lawyers are increasingly hired on platforms like PrioriLegal or eLance, and by their performance numbers – like any other business. In 6 years most attorneys will be hired on platforms. The first platform to add price and performance transparency together with a compensation structure that aligns counsel’s incentives with client’s will rule law.

The good news is that the best performers will name their own price and clients will gladly pay it. American lawyers struggle to break the $1,100 ceiling simply because they can’t prove how good they are, and many $1,000 peers simply aren’t any good. Top Queens Counsel in the United Kingdom can make many times that. Clients resent overpaying for mediocre performance but will happily pay large success fees for the very best advocates. While litigation as an industry will become significantly cheaper and faster, the best and most adaptive litigators could easily make 8 figures a year and clients will line up to pay them.