The 10 Most Important Legal Technology Developments of 2016

The 10 Most Important Legal Technology Developments of 2016

What were 2016’s most important developments in legal technology? Every year since 2013, I’ve posted my picks of the year’s top developments in legal tech (2015, 2014, 2013). As another year wraps up, it’s time to look back at 2016.

What follows are my picks for the year’s most important legal technology developments. As in past years, the numbers are not meant to be rankings — each of these is important in its own way. I also refer you back to my prior years’ posts, as much of what I said in them remains true today.

1. The legal industry gets smart about artificial intelligence.

In my top 10 list last year, I considered it big news that AI had come to legal research in the form of ROSS Intelligence, a startup that uses IBM’s Watson platform to answer lawyers’ natural-language legal research questions. Just as last year closed out, another AI company, Premonition — which says it is applying AI to the largest legal database in the world — announced a seed round at a $100 million valuation.

In my top 10 list last year, I considered it big news that AI had come to legal research in the form of ROSS Intelligence, a startup that uses IBM’s Watson platform to answer lawyers’ natural-language legal research questions. Just as last year closed out, another AI company, Premonition — which says it is applying AI to the largest legal database in the world — announced a seed round at a $100 million valuation.

In 2016, AI in legal grew by leaps and bounds. The year started with the announcement by none other than legal-research giant Thomson Reuters that it was getting into the AI game, using the IBM Watson technology to develop products specific to the legal vertical. At the time, it said it would be rolling out the first of these products in beta by the second half of the year. This week, a TR spokesperson confirmed it is currently testing a beta AI product with nine customers with the goal of launching the product by the middle of 2017. While details of the product remain sketchy, the spokesperson said it targets the regulatory space and will greatly simplify several common and complicated workflows.

Then, in a notable development in March, Deloitte and Kira Systems announced an alliance “to bring the power of machine learning to the workplace, an innovation that could help free workers from the tedium of reviewing contracts and other documents.” From there, it was a year full of AI news – an AI tool to help diagram intricate corporate structures, a self-service AI portal where law firms can configure custom AI tasks, and more.

Meanwhile, ROSS has gone from clever idea to actual product, signing deals in 2016 with several major law firms, including Baker & Hostetler, Latham & Watkins, von Briesen & Roper and Womble Carlyle Sandridge & Rice.

2. Chatbots start chatting about law.

As a concept, chatbots are nothing new. They trace their origins to the Turing test in the 1950s and the creation in 1964 of the first chatterbot program, ELIZA. But 2016 was the year they took off, driven, at least in part, by the recognition that the best user interface is a conversation, and perhaps also by Facebook’s launch of Bots for Messenger.

As a concept, chatbots are nothing new. They trace their origins to the Turing test in the 1950s and the creation in 1964 of the first chatterbot program, ELIZA. But 2016 was the year they took off, driven, at least in part, by the recognition that the best user interface is a conversation, and perhaps also by Facebook’s launch of Bots for Messenger.

In the legal field, chatbots haven’t exactly taken off, but they’ve certainly made a splashy entrance. This was due in large part to Joshua Browder, who at 18 years old developed Do Not Pay, a chatbot he launched as “the world’s first robot lawyer” to help people fight parking tickets. He later expanded it to provide free legal aid to the homeless. More recently, a group of law students at the University of Cambridge in the UK unveiled what they call the world’s most advanced legal chatbot, one designed to help crime victims gauge their legal options.

Suddenly, it seems, chatbots are springing up all over the legal field. In Canada, a company called Legally Inc. has developed Winston, a chatbot that, like Do Not Pay, helps people fight traffic tickets. The folks at 1Law have developed Docubot, a chatbot that helps people generate legal documents. Lawdingo has created a Facebook Messenger chatbot for intake of inquiries by potential clients. A bot called GRBot lets users of the messaging app Kik search the world’s laws on any subject.

While these law-related chatbots remain fairly rudimentary, they are but the leading edge of a technology that is likely to see rapid growth over the next couple of years.

3. Legal startups find stardust.

In 2016, the legal profession continued to benefit from a boon in the number, creativity and variety of legal startups. Last April, I wrote here that the number of legal startups had nearly tripled in two years. When Keith Lee pointed out that the data I relied on to make that claim — the Angel List roster of legal startups – had a lot of junk, I decided to build my own list of legal startups. My list currently has 613 entries; I am confident that it underreports the true number; I learn of new startups almost every day and I already have more to add that I haven’t gotten around to. Angel List roster currently lists 1,401 companies. Given what I learned about that list last April, I suspect it overreports the true number.

In 2016, the legal profession continued to benefit from a boon in the number, creativity and variety of legal startups. Last April, I wrote here that the number of legal startups had nearly tripled in two years. When Keith Lee pointed out that the data I relied on to make that claim — the Angel List roster of legal startups – had a lot of junk, I decided to build my own list of legal startups. My list currently has 613 entries; I am confident that it underreports the true number; I learn of new startups almost every day and I already have more to add that I haven’t gotten around to. Angel List roster currently lists 1,401 companies. Given what I learned about that list last April, I suspect it overreports the true number.

The importance of these startups in driving innovation in the legal industry is gaining wider recognition. This year, for the first time ever, ABA Techshow inaugurated a competition (which I helped coordinate) to select 12 startups to exhibit in a special Startup Alley at the conference in March. This was done, said Techshow chair Adriana Linares, so that lawyers could “see and appreciate the incredible amount of creativity and development being introduced into the profession.”

Whatever the exact numbers of legal startups may be, no one can disagree that there numbers are growing steadily and that they are helping to innovate and diversity the technology tools available to legal professionals. That is an important thing – and a good thing.

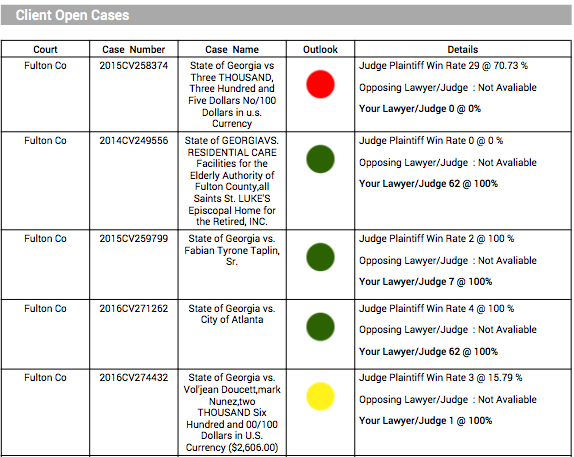

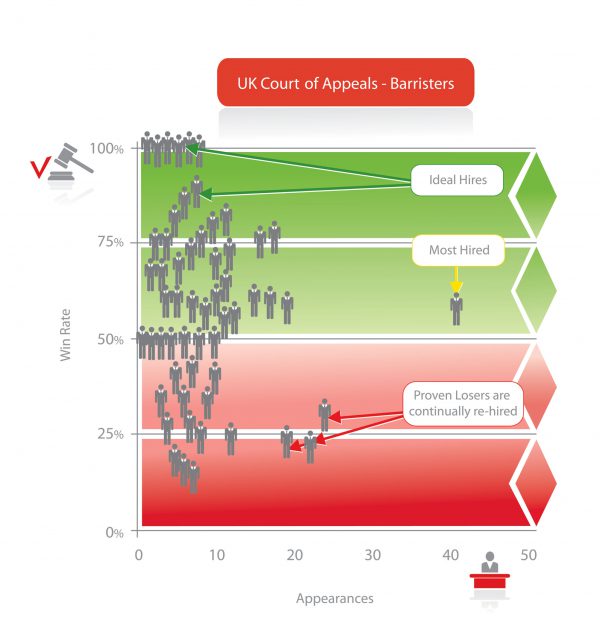

4. Analytics expand their reach.

One of my top-10 developments last year was the growing significance of data analytics in law. Well, if it was a big deal last year, it was an even bigger one this year.

One of my top-10 developments last year was the growing significance of data analytics in law. Well, if it was a big deal last year, it was an even bigger one this year.

Last year saw the acquisition of analytics platform Lex Machina by LexisNexis. At the time, Lex Machina focused solely on intellectual property law. But that, I wrote last year, was just the tip of the iceberg. This year, under LexisNexis’s ownership, Lex Machina began its expansion into other areas of law – first to securities law in July and then to antitrust in November, with other practice areas to come. It also launched various apps to make its analytics easier for lawyers to use.

Many others have also been building out their analytics capabilities. In October, Bloomberg Law introduced Litigation Analytics to provide insights on federal judges and law firms in the federal courts. Earlier this month, Ravel Law – which already had a Judge Analytics product — launched its Court Analytics to apply analytics tools to an entire court, including all its cases and judges.

The significance of analytics in law is that they provide a depth of perspective never before available. Whether you are working with litigation dockets, e-discovery collections, or transactional documents, analytics enable you to discover patterns and relationships that can enhance your understanding and strategy.

5. Tech for A2J goes mainstream.

The idea of using technology to enhance access to justice is nothing new. The Legal Services Corporation’s 2013 Report of The Summit on the Use of Technology to Expand Access to Justice powerfully made the case for technology as an essential tool for narrowing the justice gap. But advocates of tech for A2J have long seemed to exist in their own echo chamber, with more mainstream segments of the legal community deaf to their message. This year brought evidence that the mainstream is finally getting the message.

The idea of using technology to enhance access to justice is nothing new. The Legal Services Corporation’s 2013 Report of The Summit on the Use of Technology to Expand Access to Justice powerfully made the case for technology as an essential tool for narrowing the justice gap. But advocates of tech for A2J have long seemed to exist in their own echo chamber, with more mainstream segments of the legal community deaf to their message. This year brought evidence that the mainstream is finally getting the message.

For one, there was the ABA’s Report on the Future of Legal Services in the United States, which was unequivocal in its support for the role of technology, stating, “The profession must leverage technology and other innovations to meet the public’s legal needs, especially for the underserved.” This year also saw the entry of Microsoft into this area. It is partnering with the Legal Services Corporation and Pro Bono Net to create a pilot state legal-access portal. Microsoft is putting up at least $1 million to develop the portal, which backers hope will become the model for such sites nationwide.

6. Internet of Things becomes a thing in law.

Sometimes the best predictor of the next big thing in law is to watch the launches of practice groups by large law firms. If they see business potential in something, they’ll form a practice group around it. That is exactly what many firms are doing around the Internet of Things – the growing network of everyday objects with internet connectivity. Among firms that have recently started IoT practice groups are DLA Piper; Morris, Manning & Martin; and Paul Hastings. The law these groups practice spans a range of communications and technology issues and legal and regulatory frameworks.

Sometimes the best predictor of the next big thing in law is to watch the launches of practice groups by large law firms. If they see business potential in something, they’ll form a practice group around it. That is exactly what many firms are doing around the Internet of Things – the growing network of everyday objects with internet connectivity. Among firms that have recently started IoT practice groups are DLA Piper; Morris, Manning & Martin; and Paul Hastings. The law these groups practice spans a range of communications and technology issues and legal and regulatory frameworks.

But the IoT is more than just an emerging biglaw practice area. IoT is becoming a direct and integral consideration in legal matters themselves. Just recently, for example, I wrote about a legal startup called Clause that is using the IoT to develop “intelligent contracts” – contracts that can be enabled to perform themselves. I described a real-world example of this that involved the world’s first interbank trade transaction that combined blockchain technology, smart contracts and the IoT. The transaction involved shipment of 88 bales of cotton from Texas to China. A GPS device tracked the location of goods during shipment and, once they arrived, the smart contract automatically triggered the release of funds. The IoT also raises evidentiary and discovery issues in litigation and IoT devices have already themselves been the subject of litigation.

7. Tech CLE becomes mandatory.

“THIS. IS. YUUUUUUUGGGE.” So declared The Florida Bar in a tweet as that state became the first to mandate technology CLE for lawyers. The mandate came in a rule change ordered Sept. 29 by the Supreme Court of Florida. The change added a requirement that Florida lawyers must complete three hours of CLE every three years “in approved technology programs.” The rule raises the state’s minimum credit hours from 30 to 33 to accommodate the tech requirement. The mandate takes effect on Jan. 1, 2017.

“THIS. IS. YUUUUUUUGGGE.” So declared The Florida Bar in a tweet as that state became the first to mandate technology CLE for lawyers. The mandate came in a rule change ordered Sept. 29 by the Supreme Court of Florida. The change added a requirement that Florida lawyers must complete three hours of CLE every three years “in approved technology programs.” The rule raises the state’s minimum credit hours from 30 to 33 to accommodate the tech requirement. The mandate takes effect on Jan. 1, 2017.

The requirement of mandatory tech CLE came at the urging of The Florida Bar, whose Board of Governors endorsed the mandate in July 2015. The mandate was first recommended by the Technology Subgroup of the Florida Bar’s Vision 2016 commission, which was chaired by Vero Beach lawyer John M. Stewart.

I’ve been following states’ adoption of the duty of technology competence. With the same order mandating tech CLE, Florida brought the tally to 25. But it went further than any state had before. Florida will forever have bragging rights as the first to adopt this mandate. But trust me, it won’t be the last.

8. All U.S. case law gets digitized. At last.

In 1995, I wrote an article surveying the availability of court decisions online. I found nine courts with opinions online: the Supreme Court, three U.S. circuits, and five state appellate courts. For finding current court opinions, that state of affairs changed pretty quickly. When I did the same survey three years later, there was hardly an appellate court in the nation, federal or state, whose current opinions were not available online. (Although back then, courts rarely posted their opinions themselves; it was more commonly done through academic or private sites.)

In 1995, I wrote an article surveying the availability of court decisions online. I found nine courts with opinions online: the Supreme Court, three U.S. circuits, and five state appellate courts. For finding current court opinions, that state of affairs changed pretty quickly. When I did the same survey three years later, there was hardly an appellate court in the nation, federal or state, whose current opinions were not available online. (Although back then, courts rarely posted their opinions themselves; it was more commonly done through academic or private sites.)

We’ve come a long way since 1995 in access to court opinions online. Yet, surprisingly, access has remained largely limited to current cases and relatively recent historical cases. Nowhere online has there been free and open access to the entire archive of American case law.

Until this year.

In October 2015, Harvard Law School and Ravel Law today announced the Caselaw Access Project, an initiative to digitize and make available to the public for free Harvard’s entire collection of U.S. case law, which it says is the most comprehensive and authoritative database of American law and cases available anywhere outside the Library of Congress. The collection contains 40,000 books and 40 million pages of decisions from the federal courts and the courts of all 50 states, including original materials from cases that predate the U.S. Constitution. Throughout 2016, Harvard has been busily scanning these volumes. As they are digitized, they are added to the Ravel Law legal research platform, where they are fully searchable and free to anyone. The scanning is nearly complete, I believe, and Ravel has been adding cases all year.

It’s taken us more than two decades to get here, but soon we’ll have free online access to the entire body of U.S. case law. At last.

9. Avvo pushes the legal services envelope.

We were only a few days into 2016 when Avvo served up a jolt felt throughout the legal profession. It began to roll out a service offering fixed-fee, limited-scope legal services through a network of attorneys. By February, its Avvo Legal Services was in full swing, officially launched in 18 of the nation’s most populous states, with more to come. Two months later, in April, the company launched Avvo Legal Forms, a free, do-it-yourself service offering legal forms for family, business, estate planning and real estate.

We were only a few days into 2016 when Avvo served up a jolt felt throughout the legal profession. It began to roll out a service offering fixed-fee, limited-scope legal services through a network of attorneys. By February, its Avvo Legal Services was in full swing, officially launched in 18 of the nation’s most populous states, with more to come. Two months later, in April, the company launched Avvo Legal Forms, a free, do-it-yourself service offering legal forms for family, business, estate planning and real estate.

In August, a South Carolina Bar ethics panel issued an opinion concluding that Avvo Legal Services (or at least something that sure sounded like it) violates the prohibition of sharing fees with a non-lawyer. Avvo Chief Legal Officer Josh King took issue with the opinion in a blog post, writing that it “misunderstands Avvo Legal Services and fails to account for First Amendment constraints on lawyer regulation.”

Earlier in this post, I mentioned the ABA’s Report on the Future of Legal Services. That report opens with a quote from former ABA President William C. Hubbard: “We must open our minds to innovative approaches and to leveraging technology in order to identify new models to deliver legal services. Those who seek legal assistance expect us to deliver legal services differently. It is our duty to serve the public, and it is our duty to deliver justice, not just to some, but to all.”

Those are sage words. Unfortunately, many lawyers’ minds remain closed to innovation. That leaves it to private sector companies such as Avvo to push the innovation envelope. In 2016, Avvo was not shy about doing that.

10. As security burns, law firms fiddle.

Lions and tigers and bears. Hacking and phishing and ransomware. Should you be scared? Yes, you should be very scared. During 2016, it was dark and creepy out there in the world of cybersecurity.

Lions and tigers and bears. Hacking and phishing and ransomware. Should you be scared? Yes, you should be very scared. During 2016, it was dark and creepy out there in the world of cybersecurity.

Let us not forget that the biggest news story of 2016 was driven by the email hacking of the Democratic National Committee. Or that, just last week, we learned that Russian hackers had taken control of the email system used by none other than the Joint Chiefs of Staff. If it can happen to them, it can happen to you.

Consider just the last few weeks of news from Sharon Nelson’s informative cybersecurity blog Ride the Lightning. A Pennsylvania prosecutor’s office had to pay $1,400 to recover its data after a ransomware attack. A Chicago law firm was sued in a class action for failing to protect confidential client information. Hackers tied to the Chinese government penetrated the computer networks of some of our country’s largest law firms. A new email ransomware scheme is targeting law firms.

So of course law firms are all over this issue, right? Well, not exactly. According to the most recent ABA Legal Technology Survey Report, only 37 percent of law firms use encryption and only 38 percent impose any type of file-access restrictions. When the survey asked law firms what security tools they use, their most common answers were spam filters and anti-spyware software.

Perhaps next year will be the year law firms get serious about security.

Source: lawsitesblog.com