A Technician of the Robot Revolution

A Technician of the Robot Revolution

I worry about my role in the future.

Sure, pundits and thought leaders call it “legal innovation” but, frankly, I’m at risk of being replaced by a robot. And, my friend, so are you.

The machines have already consolidated their gains in automated industries and are continuing their migration into white-collar work. Artificial intelligence (AI) and cognitive computing, the “next generation” of computing, will render most paperwork (and pushers of paper) redundant. Even contracts, the bread and butter of most lawyers, will be automated—there are already small-scale examples of self-executing “smart contracts.”

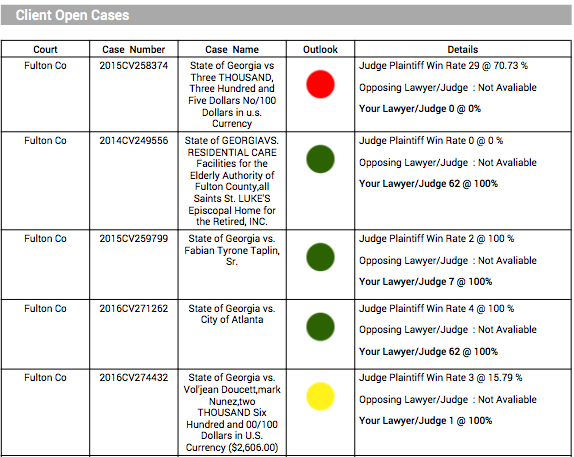

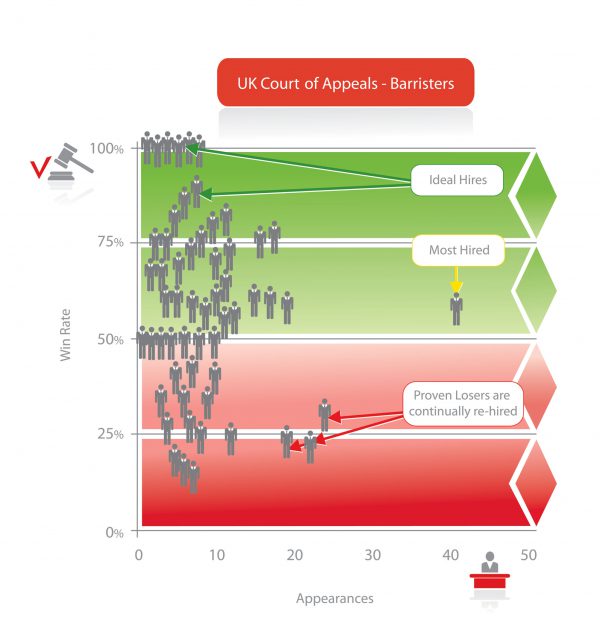

In terms of litigation, not only are computers demonstrating pretty good batting averages in predicting case outcomes (the judicial decisions of the European Court of Human Rights were recently predicted at 79 per cent accuracy using AI) but they are also pretty good at predicting your personal batting average. That’s right—there’s at least one service (Premonition Analytics) that uses AI, predictive analytics and data mining to figure out which lawyers win the most before which judge.

There’s also Lex Machina, which mines litigation data to generate insights about judges, lawyers, parties and case subjects. Law firms use it to land new clients and win lawsuits. In-house counsel use it to manage outside counsel and set litigation strategy.

These technologies represent a fundamental shift in how cases will be fought. It’s not enough to have better law or better facts; you now need a better algorithm.

I’m a traitor to my own kind in that I work within my firm’s innovation practice. We are focused on using technology to not only enhance our own processes but also help clients realize better outcomes, design more robust compliance and governance structures, and reduce costs.

Our clients are no slouches in this space either. Large institutional clients are reducing the ranks of lawyers and paper-pushers, and hiring coders and developers. Why? Because the financial burden of regulatory compliance has the potential to be significantly reduced by “RegTech” (but not replaced—as a colleague with an anti-money laundering practice keeps reminding me, “You can’t outsource compliance.”).

In-house counsel are embracing innovation primarily to drive price down. The next step is to enhance processes. In other words, improve legal processes to make legal work flow better. For instance, my firm is working to automate the client interface—think portals and dashboards. We already do large-scale process reengineering work (e.g., ever wonder how many hands in your organization touch that contract during its lifespan and whether they all really need to?) and have had sophisticated project management tools in place for some time.

In-house counsel are also redefining what is truly legal work. This a significant direction in which legal innovation is headed. Once legal services are unbundled, you would be surprised at the number of things that don’t actually need a lawyer.

A good example of this is the information-gathering phase of a file. Much of this can be done internally (and often remotely) under the guidance of lawyers. This reduces disruption for clients, and increases our own relevance and credibility in areas that truly matter.

What if a machine could ask you all those questions a lawyer is probably going to ask? In a wrongful dismissal action, for instance, there are a lot of routine questions. This is the realm of chatbots. It’s already happening: in the UK, a chatbot for fighting parking fines has overturned $4 million in fines since 2014, and won 160,000 out of 250,000 (a win-loss ratio of around 65%).

More than anything, “legal innovation” means that lawyers themselves will need to innovate. Those already practicing will need to embrace new technologies and new ideas, and—more challenging—be willing to rethink the old ways of doing things. Those just entering the field will have an opportunity to entirely redefine what it means to practice law.

I’m fortunate that my practice centres on technology and data management. I am, in a nutshell, a technician in the robot revolution. And initial concerns aside, I welcome our new robot overlords.

Kirsten Thompson is Partner in McCarthy Tétrault’s National Technology Group. She leads the firm’s Cybersecurity, Privacy and Data Management group, as well as the firm’s E-Discovery and Data Management Team. With a focus on providing privacy, data security, information governance and e-discovery advice to clients across industries, she has a wide advocacy and advisory practice.

This article was initially published in the Winter 2016 issue of CCCA Magazine. The author’s views are her own.

Photo licensed under Creative Commons by wocintechchat.com

Source:nationalmagazine.ca