This Week In Legal Tech: Rating Lawyers By Their Wins And Losses

This Week In Legal Tech: Rating Lawyers By Their Wins And Losses

Lawyers will give you any number of reasons why their win-loss rates in court are not accurate reflections of their legal skills. Yet a growing number of companies are evaluating lawyers by this standard – compiling and analyzing lawyers’ litigation track records to help consumers and businesses make more-informed hiring decisions.

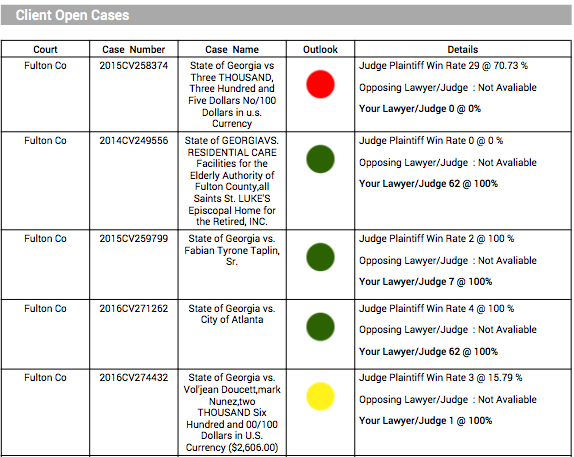

The latest to do this is Justice Toolbox, a startup that uses data mined from official state court records to compute and display how many cases a lawyer has won and lost and the lawyer’s approximate win rate. As I wrote at my Lawsites blog Friday, it currently operates only in Maryland and the District of Columbia, but plans to expand to several more locations by June.

Justice Toolbox is targeted at individuals and small businesses requiring legal help. It evaluates lawyers’ records in common types of cases, such as DUI defense, small business disputes, personal injury cases, divorces, and landlord/tenant disputes.

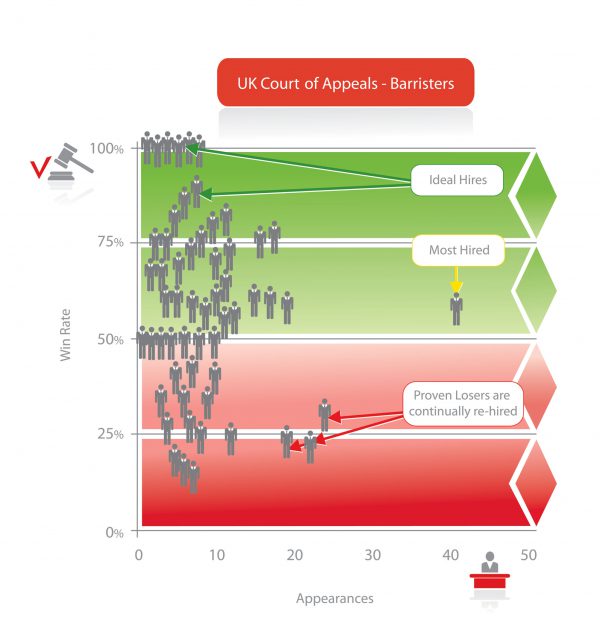

Another company, Premonition, is doing something similar for large corporate clients. Like Justice Toolbox, Premonition uses advanced analytics to evaluate lawyers based on their win-loss records. But it does it on a much larger scale. It claims to have the world’s largest collection of court data, covering the U.S. district and circuit courts, the UK High Courts, the Virgin Islands, Ireland, Australia, and the Netherlands.

“There are huge variances in how good attorneys are perceived to be and how good they actually are,” its website asserts. “Many expensive lawyers are poor performers. Many cheap Lawyers are actually phenomenal — at least in front of certain judges. Only Premonition knows.”

The analytics platform Lex Machina has its own variation of this. Its Law Firms Comparator app enables side-by-side comparison of up to four law firms, showing a variety of case-specific data, including win rates, case timing, and damages history. Lex Machina markets this not only to businesses shopping for a law firm, but also to law firms to compile intelligence on their competitors.

The shortcomings of evaluating lawyers by win rates are many. Not least of them is that so few cases ever make it to a win or loss. In criminal cases, the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts says that 90 percent of defendants plead guilty rather than go to trial. Is a guilty plea a win or a loss? The answer, of course, is that it depends. And it depends on factors not readily visible from a docket sheet or data downloaded from a court.

In civil cases, the same is true. On average across court systems, only about 5 to 10 percent of cases go to trial. Of the cases that do not go to trial, many settle, but the majority are disposed of without even a settlement. Some are withdrawn, some are abandoned, some are merged, and still others are closed for clerical reasons.

Of equal concern is that, in the nuances of law practice, it is not always obvious what constitutes a win or a loss. If a company enters into a nuisance settlement to avoid protracted litigation and the accompanying legal fees, is that a win or a loss? If a PI lawyer settles a case for $10,000 when the defendant was secretly prepared to offer up to $50,000, which side was the winner?

Finally, there is the simple fact that some of the best lawyers take on some of the toughest cases, and sometimes they lose. In those cases, the fact of a loss is not a reflection of the lawyer’s ability, but rather a result of the lawyer’s courage and tenaciousness.

In comments to my blog post about Justice Toolbox, founder Bryant Lee, a former Covington & Burling lawyer and a Harvard Law School graduate, addressed some of these concerns.

With regard to the fact that most cases do not go to trial, Lee agrees that those cases are hard to evaluate since the outcome and negotiations leading to the outcome are not public. “For now, we’re focused on using data that is publicly available, namely dockets with win/loss info, to give the public what insight we can into attorney performance.”

With regard to the point that some cases are harder than others, Lee says statistics should correct for this over time.

“If attorneys have a similar case mix, e.g., 33 percent hard cases, 33 percent medium cases, and 33 percent easy cases, then, statistically, in the long run there should be a correlation between a higher win rate and better attorneys,” he says.

Finally, to the point that an adverse judgment can actually be a win if it’s a case of reducing liability or reducing charges, Lee agree that can be true. “It’s something we’ll look into as we collect and analyze more data. We want to be careful to maintain objectivity and not make the measure too subjective.”

Given the shortcomings inherent in evaluating lawyers based on win-loss rates, it might be argued that no data is better than bad data. But I would disagree. Consumers have few objective criteria by which to select a lawyer. Win-loss records give them something more to grab onto.

Besides, this isn’t really bad data. It’s incomplete data. Win-loss records tell only part of a lawyer’s story. Websites offering this data should make this very clear to their users. But with adequate disclaimers and explainers, win-loss data can be a useful and tangible metric that can help consumers make more-informed decisions about hiring a lawyer.