In Discussion With …. Jeff Seder, Architect of Moneyball for Horse Racing

In Discussion With …. Jeff Seder, Architect of Moneyball for Horse Racing

Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | Android | Email | RSS | More

Discussion with Jeff Seder, Entremanure, and Architect of Moneyball for Horse Racing

“it’s not how fast the horse goes, it’s how the horse goes fast”

For more than three decades, Jeffrey Seder, a Harvard-educated lawyer and self-described “entremanure” has spent millions to research and refine the science of picking a champion racehorse. His remarkable insight has delivered remarkable success not least, helping the owners of “American Pharoah” spot the potential of a future Triple Crown winner in the US. His findings are challenging pre-conceived ideas of how to find great horses and we’ll give you a clue, it’s no longer just about the breeding. His concept of Moneyball for Horse Racing chimed with our own Moneyball for Law, so we just had to get him on the Premonition Podcast.

Click here for more information about Jeff Seder and his remarkable story or visit his website : http://www.eqb.com

In the meantime – enjoy the podcast, the transcript of which is below;

Andrew Weaver: Jeff, Welcome to the Premonition Podcast. Thank you for joining us.

Jeff Seder: Happy to be here. Thank you for the invitation.

AW: Great to speak to you on a number of levels. I was mentioning to Jeff before we recorded that my family actually have a background in horse racing, so on a very personal level, Jeff, fascinated to see what you’re doing or what you’ve achieved with this. And obviously the Moneyball angle from a premonition basis, from a big data basis is really fascinating particularly in a world where you wouldn’t think the data would have made the impact that it has.

So just to reel us back a bit. Take us back to the beginning. You’ll love affair with horses began with a date I understand.

JS: Yeah, I was in law school and I went on a date. She took me to a rental stable. And we went out on horses and I kinda fell in love with the horses instead of her. And started taking lessons. I said it’d be a lot more fun if I didn’t have to worry about falling off and then I started taking lots of lessons and then I bought a horse and then I rented a farm and away we went.

I don’t know if you know enough about American politics but when Richard Nixon was in there and he got thrown out for Watergate. The thing that precipitated it was after Watergate they hired a special prosecutor, Archibald Cox from Harvard and when I was in Harvard Law School he was my advisor right after that. So I had to go to him and tell him what my thesis was. I was in a law and business programme and I hadn’t done anything and it was near the end of the year and I had to go in there and talk to him about my progress, which was nonexistent.

So I went in there and I thought he was gonna throw me out and it’s gonna be a disaster. And he asked me, “Where are we?” And I said … And he said, “Well what are you in interested in?” And I look down at the floor and I said, “Horses.” And I thought that would be it and he turned around and he got this huge book. His office was in the stacks, which was like four levels beneath the earth in a dark section of the library where they store all the books and stuff.

He turns around and he pulls this huge book from behind him and he drops it on the desk and the dust all goes up and he says, “This is the statute that governs horse racing in the state of Massachusetts. I don’t think anybody at Harvard has ever looked at it. Why don’t you do that?” So I went crazy doing that and I found out that … I went through the finances of the racetrack, which was all completely sleazy and bogus and I just had a field day with it and I ended up getting a “A”. And then I thought I’d really like to do something with horses but I couldn’t see anywhere but I had no background in it. I had no connections. I was starting to be a good rider. I didn’t know anybody really and I thought, “Well, what the hell can I do?”

The only place I saw where I could make the kind of money I wanted to make was in horse racing. So I looked at that and I thought, “Wow”. The more I looked at it and through this research I had done on the racetrack it was 300 back in what they were doing and it was 1976. And the Olympics, the East German just burst onto the scene in the Olympics. And they were winning all these medals, this little country. Before that it was all a fight between the Russians and the American for gold and who had the most gold medals and now all of the sudden this little country … And everybody was horrified and the said, “How are they doing it?” And they thought there were mad scientists taking kids out of kindergartens. It turned out a lot of it was steroids but nobody knew that.

Well anyway, I was a young lawyer and I was fortunate enough to be asked to be part of a group that was starting to do something in the United States about it in sports medicine research for the United States Olympic Committee. So that was my first gig and so I started working very heavily with the people who were experts in biomechanics and all the different things that were related to exercise, physiology and sport and the more I got into it the more I realised that racing was really in the dark ages.

And I said, well, look I have this education and science … I was premed also at Harvard … education and science and statistics and business and here I am in the middle of this huge explosion of trying to be more scientific about sports and I could do this with horses I thought. And then fast forward after 20 years of starving and doing nothing and finally it turned into a juggernaut. It’s become great. 39 great one-winners we bought in the last five or six years. Four Eclipse Awards and world champions that we bought for not a lot of money and all. And just an incredible track record and last year we bought young yearling from some guy, gave us $900,000 and we turned it into $4.5 million and sell them off as two year olds.

Talk about affecting an industry and the impact of us. Although we do work with six of the top ten stables in the United States, most people don’t know who we are or when to use us or there’s cheap imitations of what we did. What we’ve taken 35 years and millions of dollars and there’s people out there kinda winging it but a lot of people can tell the difference between us and them. Except that our track record … And the crowning piece of the programme was American Pharaoh. After 37 years he won the Triple Crown and so although I did … The guy that owns him, kinda somehow I got in a fight with him right before he won the Triple Crown. I was banned from his box at the racetrack during that event. So that that kinda put a damper on the whole event.

But we had bought him the dame for that as an incredible physical specimen and she only ran a couple of races and he made her a brood mare but she was something really special. And then the sire was part of a breeding programme and he was gonna sell it and we did all the testing that we do. And he didn’t sell it and we thought we were a real part of it. And then when American Pharaoh was young he was put in a yearling auction and we were supposed to evaluate him and once again we said, the New York Times the day before the Belmont Stakes, that Friday before he won the Triple Crown the quote of the day, they have a quote of the day every day in the New York Times and that day it was me. And the quote was, “Sell your house, don’t sell this horse,” which was from that yearling auction.

AW: I saw that.

JS: And the rest was history. So that was nice.

AW: And just a quickie on that a lot of people listening to this will be from the States, will know what the Triple Crown is. But the Triple Crown is essentially the three premiere race, horse races in the States. The Kentucky Derby, Belmont Stakes and the Preakness Stakes?

JS: The Belmont Stakes, the Preakness and the Belmont Stakes.

AW: Preakness Stakes yeah.

JS: And they’re different distances and different services so it’s extremely hard to do it and what happens these days is fresh horses will meet you at each race, that didn’t go in the other races. You’re not required to go in all three. And they’re bunched fairly close together, so even if you’re a super horse, you’re gonna be tired. You’re gonna meet the best that there is in the world going for million dollar purses in each of these races and they’re fresh and you’re not. So it’s really quite and extraordinary achievement these days. And it didn’t happen for 37 years. Secretariat, people may know that name, was one of the premiere triple crown winners. One of the last ones before it stopped. The whole thing stopped. And of course your grade one races. There three year olds too.

Speaker 1: But let me just tell you about very briefly, if you wouldn’t mind Jeff, without giving away trade secrets, clearly here. But you told the owner to sell his house instead of selling this horse. What was it about that horse that convinced you? What had you spotted?

Jeff Cedar: Before I do that, let me just tell you one of the things I learned from my experience with the Olympic Sports Medicine Committee and working with American Olympic teams. By the way we made a big difference with a number of teams, was that the medical data that existed, the data that existed to understand medical, engineering, physiological … to understand these things was on normal and on sick or injured. They didn’t know about elite athletes. And it turned out that the elite athletes the data we needed was as different from normal as the injured and the sick was from normal.

And so we didn’t know, they really didn’t know. And when I created the first accurate heart rate metre that was the size of a pack of cigarettes and you could carry around. And while I was doing that I went to the world’s leading race horse cardiologists and they told me the heart rate would be about 120 beats per minute going up the racetrack because their heart’s so big and this and that and the other. And then the metre kept telling me it was like 220. And I said, “What’s wrong with this?” And finally decided they’re nothing wrong with my … They don’t know what they’re talking about. And it happened again and again and again. And I realised I had to get the data. Not only that but the equipment to get the data didn’t exist. I had to get designed and manufactured for me specifically and this was back 20 something years ago, a chip. Personal computer didn’t exist. I had to have the chip manufactured so I could get that accurate heart rate. Human metres weren’t accurate for a lot of reasons.

And so I did that again and again. I saw that a guy named Steele in Australia was doing the measuring the size of the heart, trying to do it from an EKG. But the little machine that he would measure the distance between the peaks on the EKG on the little tape that came out of the cardio machine but the tapes … They were doing it in barns.

I’m gonna answer your question. They were doing it in barns and the voltage would vary so the little motor running the tape would go faster or slower and then they were measuring the distance. It was crap data. And he still had some relationships but I said, “This is ridiculous. I need to do it … ” I found out you could take ultrasound and measure the pieces of the heart but you couldn’t do it in a stall because it wasn’t portable.

Speaker 1: But just to tell everybody this was a homemade device wasn’t it? This was something you created.

Jeff Cedar: So it was 20 something years ago or more. So we went to … We bought an Apple 2C, the first thing and then we went to military contractors outside of Washington D.C. and we got military hardware crap and then we programmed in machine language. Nobody now, it’s like 15 languages later. We programmed it in machine language so it would be fast enough because you have like 10 million things a second in ultrasound. And we build a machine that could go in the stall and you could wheel it in. And we started doing racehorses.

And we found out that the transducers were wrong so we had transducer in different frequencies manufactured for us. By the way, that machine is now commercially available. We should have patent the goddamn thing. And then we got so that we could do reproducibly and to see what we could do. And I’m gonna get back to the analytics and the big data and everything. I’ll get back to that. But to fast forward about American Pharaoh. American Pharaoh fit everything we knew. After 35 years of doing that stuff. Millions of dollars. 20,000 horses, follow every split of every race and do all these work ups on them and everything and now we’re into DNA.

But anyway the most outstanding thing about it. The other thing we found out about it was the great athletes. They were different and they didn’t have holes in them. So in the great race horses, you didn’t have to have the very best gate or the biggest heart or the most wonderful something. And a lot of people thought they did. They would fall in love with one thing they found and then they would find a horse or a person, an athlete who would have that one thing and then it didn’t work out and they didn’t know why.

That doesn’t work. You don’t need the best everything. You just need a good everything and that makes you very rare. So it’s like if you had 20 links hold the Queen Mary and they were titanium and you had one that was made out of paper make. It will break and the ship will float away. Well it’s the same thing with these athletes. So what we’re really looking for when we find all these great one winners when they’re yearlings is, when there’s no hole.

Not only was American Pharaoh had no hole. Now he wasn’t the greatest in everything. But some of the variables he had were just off the chart. One of them was his heart. In fact, I know one of the guys that used to work for us and he left and he competes with us, turned him down because he thought his heart was too big. But we were pretty sure that wasn’t the case because everything else fit. Everything fit. And yes, it was extraordinary but that’s what we’re looking for, extraordinary.

So why would we get rid of the anomalous. When we see a big anomaly wy would we throw it out? It’s like with a symphony. You can jumble notes together an infinite number of ways and you just get noise. But there’s also a whole lotta ways you can do it that are symphonies and they’re different but it all fits together and that’s what he was. And he had this huge, thick enormous heart pumping a lot of blood. And the quality of the muscle and this and that. The whole things was just extraordinary. And on top of that we couldn’t find anything else, no matter what we … traditional, non-traditional we couldn’t find a hole in this horse. So we said if this horse can’t … Unless something happens to him he’s really gonna be memorable. And he was.

Speaker 1: Yeah, amazing story. I just want to move you on to the challenge that you put into the given the traditional, and the word traditional is what chimes with us in legal services, because we are struggling under the weight of tradition and peer review and all that nonsense. And actually data shining the light on performers that we’ve never done before. So you’re challenging or have challenged the traditional view that bloodlines and pedigree are what matter.

Jeff Cedar: Absolutely.

Speaker 1: That’s what drives the value. That’s what drives the price. That’s what gets sexy headlines. But actually, what I found astonishing when I was reading some of the background research on you guys was the stats on actually how many of those horses win is incredibly low. I mean what are they … one or two percent are gonna win.

Jeff Cedar: That’s what I realised. I realised that 99.9% of the people in horse racing were losing money and they would show me the very best pedigree from the very best veterinarians, the very best owners, the very best handlers, all the smartest most experienced people and if they had 10% major horses they thought that was fantastic. And I was coming out of the Olympics, where if we had 90% failure rate we would think we were pretty awful. Right?

Speaker 1: Absolutely.

Jeff Cedar: They have no idea what they’re doing. Well, that’s not true. What they have is good but it’s not enough. So I said, “I could make a living here. I can make a contribution here.” And the first 20 years were really rough and the reason was not only did we not have the data but we didn’t have the equipment. We ended up making the equipment to get the data. And along the way we invented some stuff. We invented a bone scanner, noninvasive ultrasound bone scanner and we spun it off to Johnson and Johnson because they could diagnose osteopetrosis with it and it won the New Medical Device of the Year in Europe in 1986. And we still get royalties. That was from a little farmhouse in a corn field in Pennsylvania with a bunch of nuts from Harvard that were not doing what their dads told them to do because they liked horses.

So, anyway but we accumulated data and we had failure after failure after failure and then I met this lady named Patrice Miller. She was thrown out of a couple of prep schools and a couple of the best colleges in the United States and she was one of the first women jockeys in the United States. The second one, I think. She lied about her age and rode at 15 in a country racetrack. She had done it all.

And she got interested in what we were doing and joined us and she’s a genius at what she does and now she’s our partner in it all. And she, at that point, had worked for some of the top trainers in the United States like Rob Whitely. Hall of Famers. So she brought the traditional expertise and the curiosity to improve it and that was our turning point. Because before that we were doing technical things well and basic things badly. And she made the difference and there was a lot of conflict.

I remember one time when she was telling me … I was looking at how they were wrapping a leg and she said, “Well, that’s how Frank Whitely does it.” And I said, “Well, does Frank Whitely wear a hat?” She was gonna kill me. I said I wanted to make my own traditions. But anyway that was wrong I needed to pay attention to what Frank Whitely did and build on it and when we started doing that the whole thing started to open.

Plus, by that point I had 20 years of data. We had spent millions of dollars. I have worked other jobs I had been successful in major businesses that I didn’t give a shit about because all I wanted was the money to do my horse research. And so that’s where the money came from. And I also brought technology from my businesses. The slow motion photography, I brought that from textiles where you had to have a machine that could watch the loom, the needles all going like mad and it could immediately slow it down and look at it and figure out what to fix.

I took that over and I did it on the horses breezing on the racetrack. And I found out that again, like I did in the Olympics that the great horses ran differently than the average horse. And you couldn’t do it with a regular camera. In those day, these were cameras we didn’t have video. It was like $200,000 for shitty video these were special camera, and again military that went 500 pictures a second with film without breaking it. And then special projectors on special computer platforms.

It was incredible but we found out there were major things that we could identify that were different in the way that these really good horses ran. And we added that to our stuff. And so we do gate analysis now. And well people say, “You don’t need a camera that goes that fast.” Well then they don’t know what to look for because they haven’t got the data.

And the same thing with the heart. I see guys out there and they’re looking at the injection fraction of the heart and I know, because I got mountains of data, that’s meaning … well it has to be normal in the range. But other than that it’s not gonna tell you much. There’s all kinds of crap being sold out there. They have 100 ponies in a lab or they have 170 horses out a some guy’s barn. Something ridiculous. Well we have 50,000 horses over 15 years worked up and followed.

And we published a lot of it. We published mountains of data. Because nobody would pay any attention to us and they didn’t believe it and they couldn’t tell the difference between what we were doing and the bullshitters. So we published it. And at the time, I thought, “Well, I’m giving it away but it’s the only way it’ll legitimise it and I’ll be the first one. So I’ll get my share of the market.”

As it turned out, although it was read by the scholar, veterinary scholars I got it into the most prestigious scientific journals where it had to be refereed by those guys who were completely prejudiced against me because I didn’t have a veterinarian’s degree. But they realised … I had to jump through so many hoops but it was real. We published all this data and that was a fraction of what we have. But people still don’t … They don’t read it. They don’t use it. They don’t understand.

In the hard stuff for example, it turned out we were measuring the hearts and we couldn’t get anything. It really wasn’t any good until we got enough data. Until we had 12,000 horses over three or four years and every split of every race through the end of the three role year kind of thing.

And at that point we realised that if we separated the data from when we took the reading … So we only compare horses that are the same age very tightly within a month. Chronological age and the same sex. And the same height and the same weight. We had to have a database big enough so that if it was a 900 lb. 13 month old Philly that was 15 hands that we had enough horses that were graded stakes horses in there that weren’t just on drugs or by accident in one race or something.

In order to have hundreds of horses to compare to everything you looked at, you had to have a database of 20,000. So when we got there and we did that statistically on the computers. And then still we didn’t have personal computers. In those days I would run up to a hospital in New York and they had a huge IBM 360 and I knew a doctor there and he would let me put these huge discs on it from midnight until 7 AM. All the stuff.

And we found, “Oh my god. Look at this.” Now it’s obvious what we’re looking for. So when people go out and wing it. The other thing is it’s not easy … When we first started measuring hearts for example. And again we went to the experts and they showed us how you do it and the protocol of equine cardiology. And it didn’t work. It wasn’t reproducible. You couldn’t go in a stall and do that with a yearling running around and get the same result twice. And we said, “Well, what’s wrong with this picture?”

So we worked and worked and we ended up with a different protocol. We went around the other side of the horse. We changed the frequency of the transducer and we measured a different angle at a different part and we got so that it was reproducible. You could do it tomorrow, next week, next month or whatever. And you couldn’t do it with another technician really. You needed a really trained technician. It was not easy.

You could people the data, the instruments, you could give them the violin and the instruction manual but they weren’t going to play a symphony. They needed the experience. Anyway it got so that we could do it reproducibly. And we proved that with a huge study. And then we win after it. And the data just become obvious when we win. Some of these horses are not gonna make it.

This is Moneyball in its pure … It’s analytics, it’s big data, it’s biometrics. I didn’t do it by myself. I went and found the leading people in each of the different fields in our country and I worked with them to design our studies and to interpret our studies. So that they would be sound. But every time that I started they all thought they knew the answers and it turned out they didn’t. It’s really different.

I don’t know I get so excited and go on and on.

Speaker 1: Well it’s brilliant.

Jeff Cedar: I know what I was gonna tell you. So one of the horses in sales was offered $2.4 million. It was an unraised two year old Breezing and it was a big good luck and it had a good pedigree and it was a beautiful gate and it was fast and everything else. And it passed the vet and x-rays and everything. And it had a heart that was in the bottom quartile, maybe the bottom 10% of the breed. Small spleen and I thought forget it. Forget it, forget it, forget it. It goes for $2.4 million because they’re two geniuses they don’t need this new shit. Right, they’re not gonna spend $300 to look at a heart. And then first race was a sprint it didn’t do so hot. So they were gonna run it ina second race it was running long in a major racetrack.

And I was on the computer looking at it. And it was going off on one to five. Such a heavy favourite. And I said, “He’s gonna get to the head of the stretch and he’s gonna just die. Right cause he can’t … it’s never … That horse is not going over a mile in good company. Forget it.” So I pile on every other horse in the race, right and sure enough he gets to the end of the stretch and he gives it up the second.

And I thought, “Well, there it is.” People may not understand with all the rest of it but they understand that, right. You think they get it.

Speaker 1: I’ll tell you what I was also thinking when I was looking at this.

Jeff Cedar: The people that paid the $2.4 million are some of the most famous accomplished people in horseracing and I won’t name them [inaudible 00:25:09]

Speaker 1: And one of these things I was thinking, Jeff, was the data that you got that’s unchallengeable. All these imitators can do what they want to do with it but they haven’t got that. But they also haven’t got you and they haven’t got that instinct. For example, knocking knees and the knocking feet analysis. This morse may look good now but how’s it going to look after 20 races?

Jeff Cedar: Forget 20 two or three the guys are knocking their feet. In the gate when we breeze them some of them bang their front hoof into their back hooves and they do it every stride and then they don’t want to go in the starting gate or they don’t like trainer and their feet are … And they don’t know why. And there’s like ten things like that. Some of them when they throw their leg out, their foreleg out at the end of the leg it’s a five pound hoof at the end of a rope. At the end of every time they throw that leg out they snap their ankle and then low and behold they don’t make racing or they have a short career because they crack their specimoids.

And I wouldn’t have bought that horse because I bothered to sit there with a camera that costs $20,000. I sit there and they go by and I have screen in front of me and until the next horse goes by I see the horse going by in slow motion and I see them banging their hooves together and I see them snapping their ankles. I see them going so far back in their knees that the whole leg in the shape of a banana. So you have a thousand pound horse going 40 mph and he goes so far back at the knee it’s like up straight forward and your whole leg bends like a banana with 8 tonnes of force on it. And I know that because I had force plates in racetracks that I ran horses that I know how much force there is and the angles of it.

If I started telling you all the things that I measured … I measured the weight of the manure that was coming out of horses on the way to the paddock. We cut of legs of every horse that broke down in some of the racetracks and tested them in engineering machinery to find out … We looked at so many things and just piled at that data. And nine out of ten of them were useless. One of them became the bone scanner and we sold it to Johnson and Johnson. I told you about.

A lot of it was interesting but it didn’t do anything. That tenth out of ten would be gold. And some of the stuff I don’t talk about it really, really stupidly simple but it’s powerful and lately we’re doing the DNA. And there’s guys out there with the DNA … The big deal is the called it the speed gene. And the main thing they have is a Mycostatin inhibitor marker. And the Mycostatin inhibitor is related to precocious muscle development and there’s diseases associated that makes a whippet look like a bulldog. A baby look like weightlifter.

And so the idea was that then when they would be precocious and they would put on muscle faster and be stronger earlier and win earlier races and blah, blah, blah. And they found a relation between that and the big really good racehorses and I thought, “Well, I don’t know if that’s so valuable because I can look at a yearling or I can look at a 2-year and I can tell you whether it’s muscled up without having to get DNA out of it.” And they are different. And secondly I wasn’t a three and four year old anyway so I have time to train it. It doesn’t have to be muscled up as a 2-year old to be a valuable racehorse.

And thirdly, the idea of a speed gene is the idea of a health gene. Health is very complex, it’s made of many, many things. The performance of a racehorse is extremely complex phenomena. It’s not anchored to one thing let alone precocious muscle development. Instead of looking for a health gene the look for a disease gene. One related to a specific disease. So what I look for is markers related to specific things that I know relate to the performance of the horse. I go over all my data. And I got all these horses to do.

So I started going back and I found all these horse and I said, “Okay, I know these horse have these biometric traits and I want to see if I can find markers for it.” And so I found several markers and they have nothing to do with what the big company in horse research DNA is doing. Nothing to do with that. And I’m not advertising and I’m not selling it right now.

But it’s completely different but it’s a very, very specific thing. It’s pretty good.

Speaker 1: Well, that’s fascinating-

Jeff Cedar: But what is it based on? Data. You have to be willing to spend the time and the money … you have to be imaginative. You have to get the right people so you’re asking the right questions looking for the right kinds of data. And then you have to realise that you’re probably you’re gonna find something you had no idea was important. You have to be open.

Speaker 1: In a strange way it’s not rocket science is it. If you collect that amount of data you can have a massive impact on an industry. So tell me this, you mentioned in your discussions with the vet industry. The prejudices against you. Prejudices against you I should say. How is been more generally in the horseracing environment. What are they thinking of what you’ve done and how you’ve changed the way that you spot-

Jeff Cedar: And now the sale companies in the United States all provide these video of the breezes. Although they don’t give you a video that’s good enough quality to do what I do.

Speaker 1: And Jeff, just a second breezing is what?

Jeff Cedar: They work out the horse at a racing speed with a jockey on his back in front of the crowd. A few days before the auction. So you can look at that and they provide a regular video of that so you can look at it and slow it down. But the video is such that if you really try to slow it down it doesn’t take enough pictures per second so when you stop it the legs are all fuzzy.

So the things you want to look at you can’t. But you can old do major pattern recognition from speed of the horse. So of course what do they do. They all go by how fast the horse went. And a lot of horses go fast in ways that are dangerous or that are use too much energy so they will work out at a phenomenally fast eight of a mile but the way they did it makes sure that they can’t go a mile. So I wouldn’t want them. But they sell for the most money because they went the fastest workout time. [crosstalk 00:31:14] But I interrupted you.

Speaker 1: No, not at all. I was interested in disruption. They talk about-

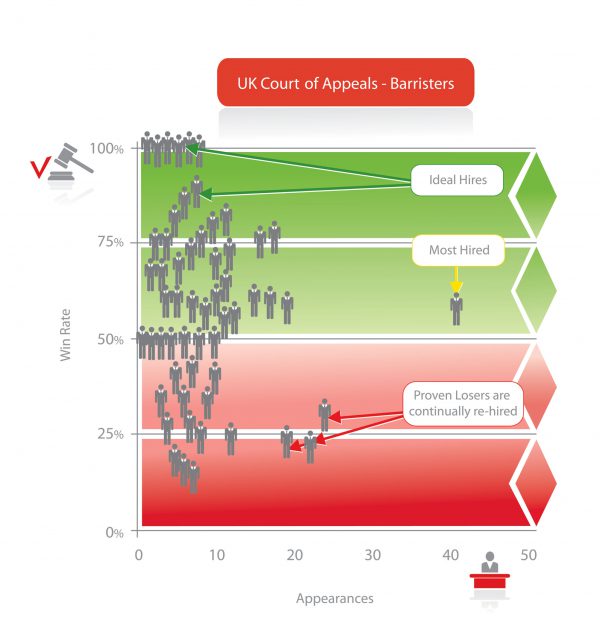

Jeff Cedar: Oh, the disruption. What do the vets think? I think they’re still sceptical. I don’t know why. We’ve published and published and published and we got our results. You can verify results. Everybody lies so they show you their big horse or whatever. We’re doing it every year. A couple of years ago we had … They’re 30,000 foals born a year in the United States. 20 of them could qualify for the Kentucky Derby, which is the hold grail. So that’s 20 out of 30,000. Five, 20% of the entire field was horses that I had picked and bought for people.

Now there’s a lot of bullshitters out there who say, “We picked that horse.” But they pick a hundred horses at the auction and then one of them does well they picked it. I’m talking pick it and buy it, right. Not out of a hundred where an idiot could go and if I’m allowed to pick a hundred I could get a good horse, right? Out of a major sales.

But anyway, so we had five at the Kentucky Derby at low odds, right? And then we had two or three a year every year. And nobody noticed so I published an ad that said, “Statistics 101, my father said three flukes is a trend and I listed whether the horse would qualify for the Kentucky Derby as three-year olds. Like five years in a row. It had zero impact on our business. And it’s just impenetrable. So I’ve decided, it used to make me crazy, now I think, “Thank you god. I can buy the horses I want off them because the others aren’t doing it.”

There’s a couple of other guys who are out there that are doing it and copying what I do and most of them without the data. But sometimes they fall on the same horse we fall on. The other thing is we can’t get the horse we want because if it has everything that traditional people want and it has the other stuff than I’m gonna be competing against Michael Tabor when I’m bidding and I can’t afford to. Not because he knows what I know but because it has all the traditional stuff. He doesn’t know it has the other stuff too.

So, that’s a problem but those guys are never gonna hire us. And then there’s bullshitters out there who claim they do the same thing we do because they use big words. I can’t believe people hire them but they do.

Speaker 1: Well, it’s a brilliant story. Jeff, I’m gonna wrap it up there. There’s a lovely saying, I’m not actually sure if it was from you or your colleague Patrice but, “It’s not how fast the horse goes, it’s how the horse goes fast.” Is that yours or Patrice? Yeah, it’s a brilliant, brilliant-

Jeff Cedar: Yeah, that’s me. We don’t look at how fast they go. We look at how they go fast.

Speaker 1: Well on that fantastic note. We’re gonna put some links at the bottom of this podcast for people who actually want to find out more about the Jeff Cedar EQB. Jeff thank you for joining me and thank you so much for all the amazing information and background about the disruption you’re bringing to horseracing.

Jeff Cedar: Well, thank you and I hope I can get to be more disruptive.

Speaker 1: Well good luck to you. Thanks again Jeff.