alt.legal: The Forecast For Legal Analytics Is Mostly Sunny

alt.legal: The Forecast For Legal Analytics Is Mostly Sunny

alt.legal: The Forecast For Legal Analytics Is Mostly Sunny

By ED SOHN

Ed. note: This is the third and final post in Ed Sohn’s three-part series on AI and the law. As always, the views expressed here are strictly Ed Sohn’s and do not reflect, in any way, the position of his employer, Thomson Reuters.

“So you’re telling me there’s a chance.” said Leicester City FC to the preseason odds-makers, basically. In the face of relegation and 5000-to-1 odds, Leicester City proceeded to outplay the best teams on the planet and win the Premier League. In the Midlands of England, 240,000 fans poured into the streets and danced atop of buses. Their team had beaten tremendous odds, team after team, all season long.

“That’s why they play the games,” said millions of sports fans, smugly from their armchairs. If odds-makers’ probabilities were always right, why play the games?

Leiceseter beating the odds is, by definition, the exception to the rule. But odds-making is getting far more precise across the board. Petabytes of Big Data are being mined with artificial intelligence and machine learning, yielding new insights and forecasting abilities in elections, satellite imagery, even food conservation. And the legal industry is no exception to this widespread movement, as covered here and here.

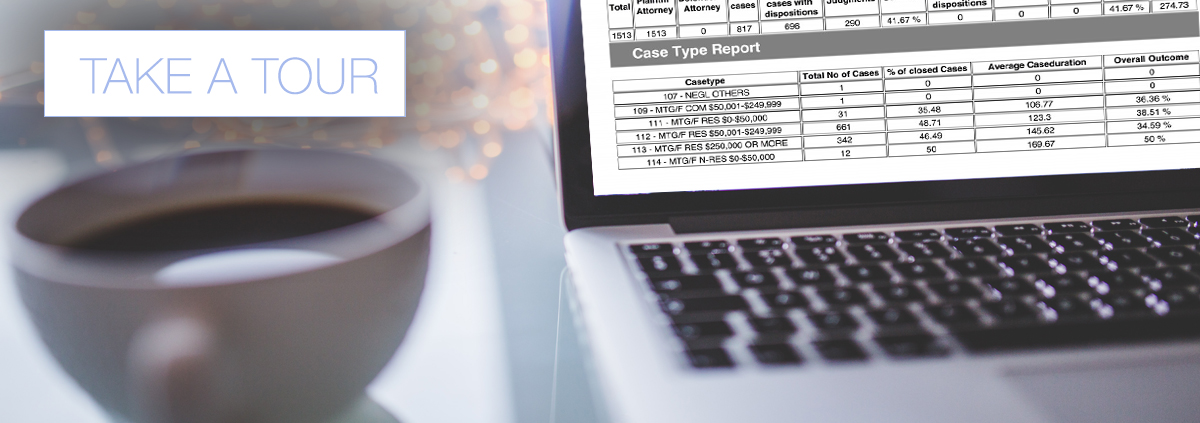

Now a new set of “legal analytics” tools is on the rise. These tools analyze past legal reference data to provide insights into future outcomes. Legal analytics quantitatively forecast a judge’s holding in litigation or an examiner’s allowance of a patent application, based on the presence of a variety of factors.

The implications trigger a dizzying battery of questions. Is the tech trustworthy? Could this data help corporate counsel defensibly quantify risk? What would this mean for insurers, litigation financiers, and others who bet on litigation risk?

And the one that bothered me most: what if the forecasts create a prediction bias, impacting how decisions are reached?

I needed some answers. And I needed my head to stop spinning.

Finding Patterns in the Matrix

I spoke with Daniel Lewis, co-founder and CEO of Ravel Law, a company focused on easier, data-driven legal research. Lewis, a Stanford law graduate, explained: “We’re layering analytics on top of archives of case law data.” At the heart of Ravel is how the system is trained. “The magic really happened when our team of lawyers worked hand-in-hand with engineers to give training to the system, what we call supervised learning.”

By analyzing cases, Ravel could find “that certain judges are re-using the same language over and over again, or according themselves to patterns, like focusing on the third factor in a four-factor test.” Ravel then leverages those insights to help lawyers anticipate how their motions will be decided before a specific judge and what language and arguments might be most persuasive.

“A few weeks after we’ve given them a report, firms have come back to us with judges that ruled exactly as we predicted, using the precise language we highlighted,” said Lewis.

“Do you see lawyers digesting these findings to adjust their litigating strategies?”

“Yes, we’re starting to see this tool in the hands of practitioners getting extraordinary results,” Lewis replied. “Lawyers may adjust their skills and how they practice. But that’s a positive. They will have more opportunities to practice better.”

“And what about judges?” I asked, trying to restrain myself from tangents. “Could Ravel change the way they decide cases? At what point does the tail wag the dog, and we have to deal with a prediction bias of these findings?”

“Well, more often than not, judges view what we’re doing as a positive,” Lewis mused. “In fact, I have heard California Supreme Court judges frustrated by attorneys focusing on the wrong arguments. They can’t preemptively tell attorneys, ‘Hey, I want you to argue about this one point.’ So judges welcome attorneys that have tailored their arguments to what judges have cared about in similar past cases.”

I admired the win-win: lawyers arguing what judges care about. Imagine that. “So ultimately, if legal analytics helps advance legal practice, who will reap the benefits?”

Lewis replied, “Corporate counsel will be managing risk better. Analytics provides more certainty about what will happen, and counsel can leverage the data to forecast business outcomes.

“But also, for individual practitioners, the world of analytics holds powerful augmenters of their skills, and that imparts confidence. Even five years ago, a lawyer doing legal research had to struggle with the cold sweats, the notion that he missed something.”

A slight shudder came over me. I was definitely that lawyer five years ago.

Lewis continued, “With Ravel, we hope that our tools will make those attorneys more confident, faster, and more thorough. Lawyers will be more satisfied with their jobs, more competitive and more effective.”

My head had stopped spinning. The pitch was enticing.

Where else was this type of analysis happening?

Words (In Patents) With Friends?

“No patent lawyer could do what we’ve done,” declared Drew Winship, co-founder and CEO of Juristat, a startup focused on patent analytics. Juristat just launched Etro, a new tool that analyzes the language in a patent application and forecasts important outcomes. For instance, Etro predicts which tech center the application will be routed to, the likelihood of its rejection on an Alice basis, whether the patent will be allowed, and the chance of an office action. “We’ve put a tank in the arsenal of a patent attorney.”

Etro, Winship enthused, required a massive and careful analysis to build. “We looked at every patent application in the last 20 years, had a neural network read the applications and analyze where the applications are filed in the PTO. We took a number of factors into account, including how the patent office has changed over time, even how it changed under the tenure of different heads of the patent office.”

I was getting it, almost. “Not only can an applicant get a sense of their application’s outcome…”

“We can now recommend words that will get the applicant into the best patent center with the highest chance of allowing your patent,” Winship explained. “Say you use the words ‘clicks’ in your patent application. It may end up under review of an advertising center, but if you used the term ‘user interactions’ it could end up in a different center that more aligns with your interests. Controlling which tech center your applications go is extremely important.”

The benefit of any single change is incremental, but it makes a difference. “Certain word choices might improve your patent’s chance of getting into a beneficial center by 5 percent. But you make some other changes that net you 5 percent here and 5 percent there, and it really starts to add up. Enabling your company to protect its inventions could be the difference between it thriving and folding up shop.”

“What about outside counsel? If you can improve things so much, how does that affect current patent attorneys and their practice?” This is always a delicate topic with attorneys.

“We have had to tell some law firms that, based on the data, they’re just not representing their clients as well as they could. They were uncomfortable conversations.” Winship did not sound uncomfortable at all.

Head spinning again, I moved on to my prediction bias question. “What is the PTO going to do with this type of visibility? Will the data start influencing their positions?”

“Interestingly, people don’t really change their decisions, even if informed with more data, because people don’t change their fundamental world views,” Winship explained. “Just look at, for example, Ginsburg and Scalia. They knew their opinions reflected certain schools of thought, and they knew that they sometimes moderated each other on the Court, but it didn’t change how they ruled.”

It made good sense. Examiners – and judges, for that matter – are not motivated to decide a certain number of decisions a certain way, irrespective of the averages.

I’m A People Person

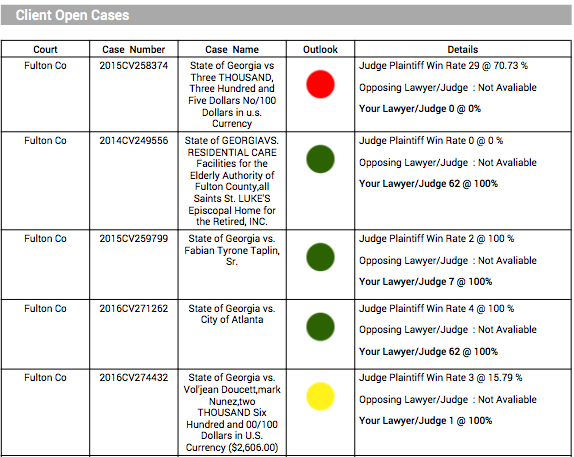

Toby Unwin, co-founder of Premonition, focuses on a slightly different statistical relationship. (See also this excellent interview he did with Zach Abramowitz.) “At Premonition, we don’t analyze the facts or the law. We focus on people. We know which lawyers win with which case types and which judges. And the special sauce of Premonition is that we’ve figured out how to do that by machine.”

Immediately, I sensed Unwin’s brilliance in this area. (Or, it may have just been his British accent.)

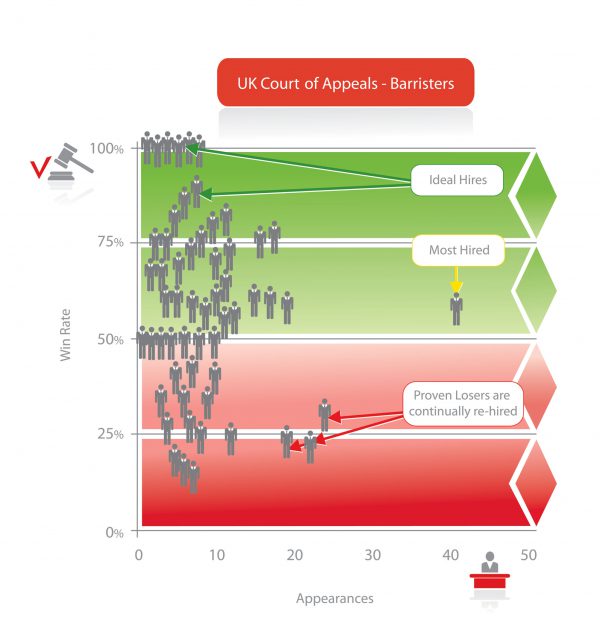

Either way, Unwin continued: “The old saying goes that ‘a good lawyer knows the law, but a great lawyer knows the judge.’ It’s true: we have found that the judge-attorney pairing is worth 30.7 percent of an outcome. That’s why we focus on discovering the attorneys that win. Winning matters.”

Winning matters? The Biglaw litigator in me immediately got defensive. “Well, what really constitutes a win?” I argued. “Many times, a beneficial settlement is a win for the client. Certain attorneys might take disproportionately harder cases, so their win rates might be a little low.” That’s why they play the games, I grunted silently.

“You’re an attorney, right?” Unwin seemed amused. “The only people that get uncomfortable about evaluating attorneys by wins are attorneys. Everyone else in the world agrees that they would want a lawyer that wins over one that does not. When attorneys try to tell us that winning isn’t important, we tell them that clients seem to like it.”

I still felt this was overly reductive, but after Unwin unpacked a little bit of Premonition’s scoring system, I could see that plenty of nuance was involved. Judgments were scored for the plaintiff, dismissals for the defendants, but motions and other non-dispositive proceedings are also scored.

What to do with this information? Unwin teased out the endless possibilities, apparently relishing my headspin. “Clients, of course, want to select an attorney on the basis of winning. But other users include insurers and re-insurers that can mitigate claims risk by hiring the right lawyers.”

Before I could play out the implications, Unwin forged ahead. “Other users include law firms that want to do marketing, proving that their firm’s lawyers win more than others. Or even attorney recruitment, to identify lateral hires that win. Some firms want to use our data to select good local counsel that wins disproportionately more in front of a specific judge.”

“There’s just so many ways to use this data.” I could think of a few more myself.

“It’s a staggeringly wide thing,” Unwin agreed. “Every few days, we think of something else we can do. We’re bringing transparency to the justice system.”

Warp Speed Ahead

Even at the pace these tools are advancing, they are just scratching the surface of what’s possible. My colleague at Thomson Reuters, the esteemed David Curle, agrees: “There are so many things it can be applied to, including legal spend, contract analysis, and information governance. Just predicting outcomes in cases is a limiting way to think of it.”

In the bestseller The Signal and the Noise, Nate Silver writes: “We have to view technology as what it always has been—a tool for the betterment of the human condition. We should neither worship at the altar of technology nor be frightened of it.” (291)

It is worth remembering that legal analytics, like all legal tech, exists to advance legal practice. With the help of new data and insights, good lawyers will continue to move the needle with innovative arguments. New precedents are set all the time, even in the face of overwhelming odds.

After all, that’s why they play the games.

Ed Sohn is a Senior Director at Thomson Reuters Legal Managed Services. After more than five years as a Biglaw litigation associate, Ed spent two years in New Delhi, India, overseeing and innovating legal process outsourcing services in litigation. Ed now focuses on delivering new e-discovery solutions with technology managed services. You can contact Ed about ediscovery, legal managed services, expat living in India, theology, chess, ST:TNG, or the Chicago Bulls at [email protected].