Anecdotes, Analytics and Finding the Best Lawyer

Anecdotes, Analytics and Finding the Best Lawyer

Anyone who tells you “winning isn’t important” usually doesn’t have any skin in the game, or is a member of the legal profession, and whilst lawyers won’t profess that approach too readily, we have direct experience that it’s the case within many law firms.

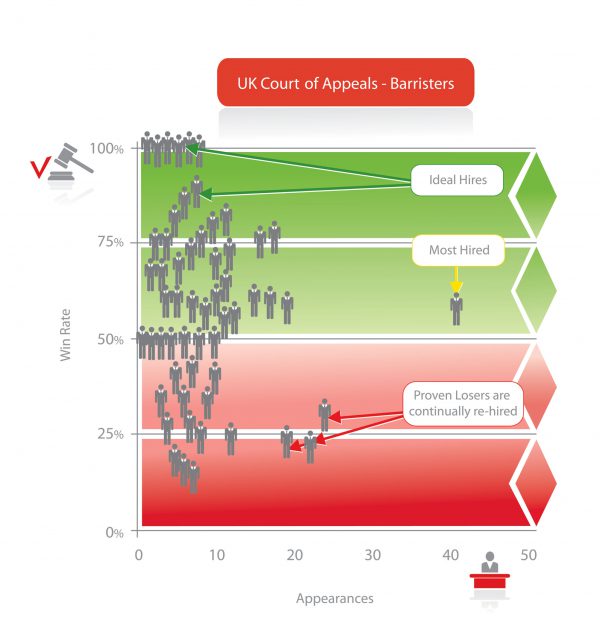

If many lawyers take an ambivalent view about winning, the consumer of legal services most certainly does not. With litigation, in particular, customers want to know they’re instructing the lawyers with the best possible win/lose case ratio.

Until recently it was almost impossible to select on performance and instead, instructing a lawyer was almost always based on word of mouth recommendations, peer reviews, market reputations. An obfuscated buying process which worked for the sellers but clearly, delivered very mixed value for the buyers.

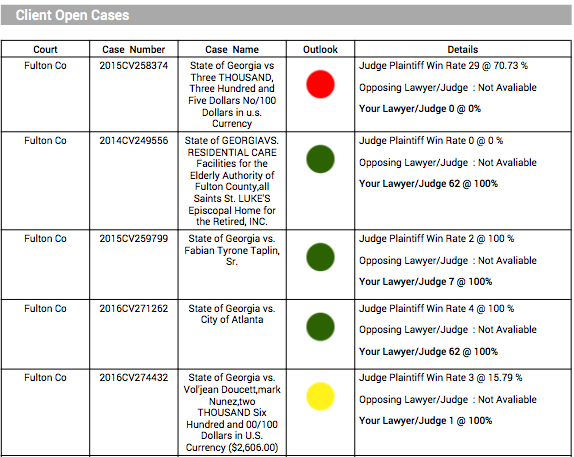

But with the advent of artificial intelligence-driven legal analytics, it’s become possible to calculate courtroom performance statistics, including:

• winning percentage (or win rate)

• average case duration

• average settlement payout

So where does that leave the traditional legal directories, who judge their recommended lawyers on the basis of peer review and market research but not, on data?

Our very own UK based director and experienced legal consultant, Ian Dodd, asked that very question in a provocative series of widely-read takedowns on LinkedIn:

“Essentially, you get some of your mates to say nice things about you (you’re not going to do otherwise, now, are you?). Then you pay (how much depends on how much of it you want to be in print) the directories to reproduce these nice things and come up with some artificial rankings in a host of different categories.

They’re artificial because they’re based on qualitative and subjective comments, the sources of which are not treated to any moderation or leveling to ensure each comment is weighted to equivalence.”

The response to this piece from lawyers and law firm marketers was, if anything, even more enlightening. While a few cited ways that firms made use of the directories (from evaluating the market standing of a prospective hire to using directory rankings to benchmark progress), no one was able to raise a compelling argument as to whether the information the directories provide has any basis in fact.

According to the picture drawn by the commentators, firms submit to the directories the way primitive people continued to perform rituals long after their meaning had been forgotten—no one knows what the ritual does, but no one wants to be the first to stop doing it lest they are struck dead by a bolt of lightning (or lose their healthy search ranking).

For consumers of legal services, legal analytics provide a much clearer picture. So long as you (or an analyst in your employ) knows the right questions to ask, the numbers are available to provide an answer. Key considerations might include:

• Areas of Specialization: It’s easy to claim expertise in high-demand specialties like drone law, but do they have a significant body of experience to back it up?

• Home Court Advantage: Sometimes familiarity breeds success. Which attorneys post the highest win-rates in the district where your case has been filed?

• Judge’s Favor: If you know the judge assigned to your case, analytics can reveal which lawyers they side with most often. Outliers have been found that have racked up 30+ consecutive wins in front of a certain judge. It may not be fair, but at least the unfairness is on your side.

Given the choice between idle chatter and a clean printout showing an attorney’s track record in court, most clients now elect to go with the empirical evidence legal analytics provide.

If you’d like to read more articles about these subjects then visit our main article on legal analytics.