Can big data really pick out the best lawyers?

Can big data really pick out the best lawyers?

Can big data really pick out the best lawyers?

30 July 2015

By Chloe Smith

Topics: The Bar,Courts business

The use of analytics and big data may transform the way lawyers are instructed, but it’s not perfect.

The use of big data can have its place in helping counsels chose which lawyers to instruct, but data alone will never be able to reflect all the factors that really determines what makes a good lawyer.

Big data has long been heralded as something companies can wield to improve their operations and make better, more informed decisions. And with a US startup which describes itself as the ‘Moneyball’ of legal analytics, big data is being taken to the legal profession.

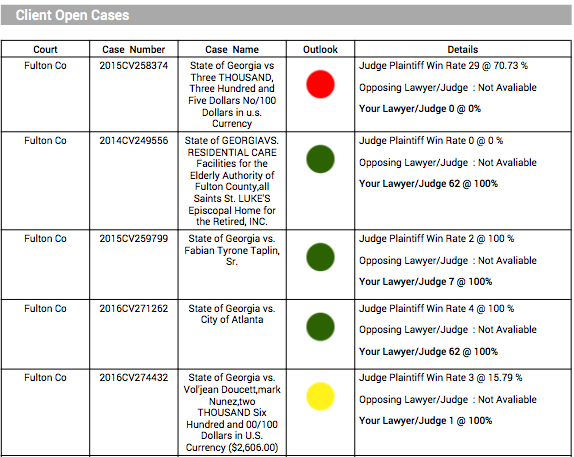

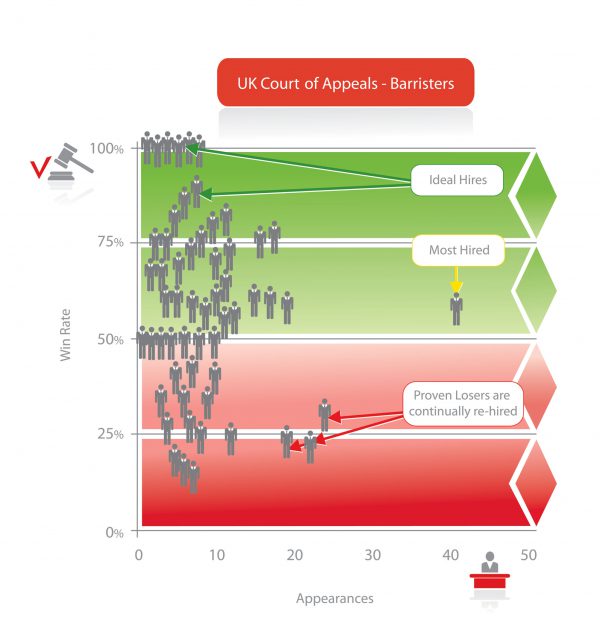

The analytics company Premonition has released a report which names the top High Court legal performers based on win rates, claiming that under the current system often the underperforming barristers are the most likely to get rehired.

The data does paint a different picture than in some of the legal directories. While some of the chambers Premonition ranks highly are the names that often appear top in the legal directories, some of the others, such as Monckton, which came second in the study, do not normally appear among the list of the highest ranked overall sets. Meanwhile, the two sets of chambers and partners ranked as top in 2014, 39 Essex Street and Kings Chambers, are not mentioned in the list of the top-seven sets named by Premonition.

But the rankings used by Premonition fails to take into account the different specialisms each chambers might have. A chambers that has been ranked highly for overall performance in the High Court might not have the best barristers to help on a big commercial dispute or in a complex intellectual property issue.

And although the primary role of a barrister is to ensure their clients are more likely to win, this alone is not all that matters when it comes to instructing a lawyer. Often their ability to get on with the client and whether they are a cultural fit with the firm can be just as important.

In a session on managing the underperforming barrister at the Institute of Barristers’ Clerks conference I attended last month, one of the primary reasons clerks gave for a barrister not being rehired was that they did not engage with the solicitor instructing them.

While this sort of data could have its place in helping companies decide who the top lawyers are, all the data in the world will not be able to stand in for the experience needed to understand what makes the best lawyer to instruct for a particular case.

And as my colleague pointed out, data can be deceiving. When Liverpool relied in part on big data to decide on their next transfer, it told them that Andy Carroll was worth £35m. Two years later they sold him to West Ham for £15m.