Could Your next Lawyer Be a Robot? Tech Firms Making Case for Artificial Intelligence

Could Your next Lawyer Be a Robot? Tech Firms Making Case for Artificial Intelligence

Originally published by, MiamiHerald.com – Author: Tarpley Hitt – April 18, 2018

Early in his career, Andrew Hall, an old-school Miami attorney whose Coconut Grove firm has sued governments from Cuba to Sudan, worked on a lawsuit that lasted three full years.

The case was cartoonishly complex. The Vietnam War was sputtering to an end and McDonnell Douglas Aircraft, then America’s largest manufacturer of jet airplanes, had defaulted on a contract involving the delivery of 99 jets to Eastern Airlines. There were over a million documents put into evidence and almost 300 witnesses. The massive operation employed so many lawyers, clerks and paralegals, they resembled a legal militia more than a legal team.

“We didn’t have a lot of computer tools available to us,” Hall said. “We ended up working in this huge warehouse with a couple hundred people sorting data all the time.”

That was in 1972. Half a century and an on-going technological revolution later, legal work is undergoing radical change.

“Today, using artificial intelligence, that case would probably involve a team of five lawyers and a couple experts,” Hall said. “The trial would last a third of the time. That’s artificial intelligence dealing with complex data.”

Andrew Hall, a Miami attorney with decades of experience, says artificial intelligence programs are already streamlining legal research work.

Andrew Hall, a Miami attorney with decades of experience, says artificial intelligence programs are already streamlining legal research work.Machine learning is already taking over the rote, replicable tasks of the legal industry — a trend that tech experts and entrepreneurs, including one start-up in Miami, expect will only expand. Flash forward a few more generations of A.I., and flesh-and-blood lawyers may face the same threat already costing legions of blue-collars workers their jobs: replacement by robot.

Human lawyers are wary of these advances. One former Florida public defender drafted a half-serious treatise on the subject, pushing “to dismiss claims that a chatbot can do an attorney’s job.” When asked, many South Florida attorneys will mount a spirited defense against the rise of the law machines. Like this one:

“A plaintiff is entitled to a jury of their peers. Robots are not their peers,” said Todd Levine, a litigator at the Miami firm Kluger, Kaplan, Silverman, Katzen & Levine. “By the same token, if the people are on the jury, they’re not going to listen to two Amazon Echos argues with each other about whose side makes more sense.”

Still, there is no debating that advances in artificial intelligence have already altered the button-downed world of law. If all available legal technology went into effect immediately, a paper from MIT says, automation could perform between 2.5 and 13 percent of lawyers’ work each year.

Hall’s airline contract case, for instance, would now be sped along with “electronic discovery” — a widely-used practice where mountains of legal files are digitized into databases searchable from a smart phone.

That MIT study was two years ago and legal tech start-ups from Los Angeles to London say the pace of change has only accelerated since.

One wave of legal tech comes straight from Miami. Recently, two British ex-pats launched a firm called Premonition Analytics out of an innocuous office building on Biscayne Boulevard.

The company logo for a Miami start-up firm that has developed an artificial intelligence program that sifts data bases to find lawyers for clients.

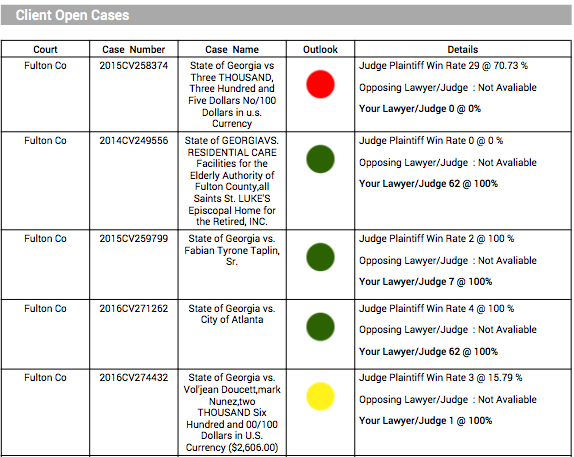

The founders, self-described “serial entrepreneurs” Guy Kurlandski and Toby Unwin, cringe at the term “legal tech,” preferring the more Orwellian “perception-reality arbitrage.” Whatever you call it, Premonition has amassed the largest legal database in the world, and designed an artificial intelligence program that aims to help clients find the lawyer best suited for their case.

“Sitting here in Miami-Dade, there are approximately 17,000 attorneys,” Kurlandski said. “It’s about 128,000 in the state. When you have a business to protect or a family to protect and you’ve been sued, how do you find the best defense attorney?”

The actual number is 105,990 statewide, and 15,872 in Miami-Dade as of March 1, but point taken––it’s hard to winnow down the options, to find the best attorney for your lawsuit, judge, and budget. It’s an AI service that maybe the industry could live with — a practical tool, and value, for lawyers and their clients.

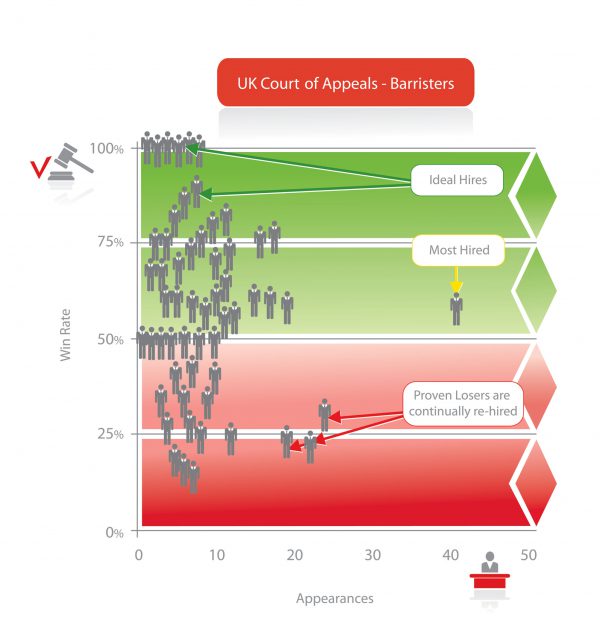

That’s Premonition’s pitch, and their solution boils down to something like legal Moneyball, where an AI evaluates lawyers based on their success rates for particular kinds of cases, in front of specific judges.

Guy Kurlandski, co-founder of Miami start-up Premonition Analytics, which has created an artificial intelligence program that aims to help clients find the lawyer best suited for their case.

Guy Kurlandski, co-founder of Miami start-up Premonition Analytics, which has created an artificial intelligence program that aims to help clients find the lawyer best suited for their case.“We train the AI to go through the dockets en masse,” Kurlandski said, “figure out the outcomes, and gather any information that would give us an indication of who was the winner and who was the loser.”

A lot of new legal technology works like Premonition––streamlining simple and predictable activities, like trying to find an attorney or the right piece of evidence. A start-up called Legalist, for example, crunches data to predict whether a case will win, and finances the legal expenses of anticipated winners. Another firm, Lex Machina, offers legal analytics aimed at helping attorneys formulate their arguments.

All those technologies operate as complements to human lawyers, but some tech developers are aiming to supplant them. Last spring, two companies––LISAand DoNotPay––rolled out competing models of what they each called the “world’s first robot lawyer.”

DoNotPay, which launched last year in the United States and in the U.K. the year prior, is a chatbot that poses users a series of questions and then automatically appeals their parking tickets. The bot has also assisted in banking charge contentions, airplane ticket refunds, landlord disputes, and asylum applications for refugees. In September, the chatbot added a feature that allowed users to sue Equifax, the credit monitoring firm which exposed 143 million Americans’ financial data last summer, for up to $25,000.

LISA, which acquired another legal AI called BillyBot last year, runs a similar program. After a few automated exchanges with clients, LISA drafts quick, free and legally binding non-disclosure agreements, or NDAs.

Bots like these could serve a substantial benefit for consumers, providing services that would normally require the expertise of a lawyer at little to no cost––like TurboTax for lawsuits. DoNotPay’s 20-year-old founder Joshua Browder, told NPR he wants to “level the playing field so anyone can have the same legal access under the law.”

Lawyers, you may guess, are not all thrilled by the progress. Premonition’s Kurlandski said many law firms are resistant to programs that will make their work more efficient.

“A lot of products in legal tech are good, and they get their tires kicked around, and everyone looks at it and talks about it,” Kurlandski said. “But there’s a reluctance to actually use it. The business of law is just not built around efficiency.”

And many legal professionals argue it could be a while, or never, before robots or legal tech programs take on the primary work of lawyers, which is less standardized and predictable.

“I honestly don’t see the reality of robot litigators striking us in the near future, maybe even at all,” said John Stewart, president-elect designate of the Florida Bar Association. “It’s never just technology that’s the solution. And it’s never just the lawyer that’s the solution. It’s the combination of the two.”

Robot litigators not only pose a substantial technological difficulty, but the potential displacement of human legal roles by machines would almost certainly veer into lawsuits and constitutional questions. Over the years, state and national bar associations have often fought the use of computerized legal advice. The tech firm Legal Zoom, for example, spent years battling state bar associations from North Carolina to Missouri over providing what the associations alleged was unauthorized legal consultation.

Even if artificial intelligence won’t replace lawyers wholesale, could it still affect the legal job market?

Litigators, judges, and big firm partners aren’t likely to feel heat from robots any time soon, but lower level staffers and recent law school graduates may find themselves competing with algorithms. A 2016 report from the consultant group McKinsey found that 22% of a lawyer’s tasks and 35% of a law clerk’s tasks could be automated. In 2017, JP Morgan began using a program called Contract Intelligence. Contract Intelligence, or COIN, can complete work which once took legal clerks 360,000 hours in a matter of seconds.

Still, Stewart suspects that these technologies won’t kill jobs, so much as change them. Last January, the Florida Bar Association added a technology component to their Continuing Legal Education program, making Florida the first state to require technology training of its lawyers. Stewart said the additional schooling will help Florida legal professionals keep up with automation.

“There’s a rule in Florida that says you have to be competent to practice law,” said Stewart, who practices in Vero Beach. “That sounds kind of simple, kind of silly. But we changed the comment on the law of competence, to include that a lawyer has to understand the benefits and risks associated with the technologies in their practice areas.”

Hall suspects legal jobs will evolve with technology, but won’t disappear.

“Human beings are very innovative. We’re going to find a way to get in trouble more often if you give us more time,” Hall said. “Anybody who thinks, oh my god, hundreds of thousands or millions of billable hours will disappear –– I bet they won’t. There are always more cases.”

Miami Herald Writer Tarpley Hitt can be reached at [email protected].