Melissa Coade speaks to members of the Australian bar about their perspective on how innovation has transformed the advocate’s approach, from chambers to the courtroom.

A dedicated and growing conversation among lawyers in government and private practice about technology and the law has flourished, perhaps in part because the impact of technological innovation on business is apparent. Professional bodies representing Australian barristers have also responded, albeit in different ways and with a little more caution.

There have been fewer surveys conducted with members of the bar than members of the various state law societies. However, recent years have seen some of the Australia’s larger bar associations in New South Wales and Victoria establish committees focused on innovation and technology.

At the International Bar Association (IBA) conference held in Sydney last October, themes inextricably tied to technology and law dominated the program agenda. A few months before that congregation of practitioners, mainstream media was gripped by the concept of giving legal status to robots that was being considered by the European Union. A draft report presented to the EU’s lawmakers had suggested attaching civil liability to “smart autonomous robots” and creating a code of ethics for the manufacturers of such products. In 2016, a joint conference hosted by the Australian Bar Association (ABA) and Victorian Bar convened a panel of chief justices who spoke at length about technology and the courts.

Both at home and further afield, the advocates of the legal profession are thinking about where new innovations may take their vocation and its broader impact on justice. Here, leading barristers share their views on just how far these advances take the bar and how they have transformed the realities of day-to-day practice.

Time to transition

Taking his interview over the phone from Perth, Western Australian barrister Joshua Thomson SC spares 30 minutes to share his evolving experience with technology and practice. For most senior practitioners like Mr Thomson, setting aside the time to research, explore and self-teach the range of tech-offerings that are available to barristers can be difficult.

“I certainly see the way of the future as embracing technology as a tool. And I think that there is a long way to go in both legal firms and at the bar in making full use of the potential of technology,” Mr Thomson says.

“There is often a lag in trying to implement those things, just out of a fear of how it will work or because barristers are very much time-consumed with other things. They do not want to experience by dropping a few hours here in order to make up quite a lot of hours down the track if they can get technology working.”

For a busy sole practitioner, exploring the limits of a software program before committing to a new one, and then learning the ways of the alternative solution, takes patience. The trial and error required to make a strategic decision about what software to invest time in can also be a taxing process, Mr Thomson says. The silk shared his experience of moving from Microsoft OneNote to PDF Annotator (created by GRAHL software design) as an example of a process that required time to adjust to.

Previously the PDF alternatives to Microsoft OneNote had the problem of what Mr Thomson says a “clunky and haphazard” writing function. He says he had to wait for a new PDF product to come onto the market before making the decision to switch.

“It took a little bit of time for me to find a really good program like PDF Annotator, which allows me to write directly onto the screen, do links and to highlight and draw on it like it is a piece of paper,” Mr Thomson says.

“Until quite recently, I used the Microsoft OneNote program to store and utilise my electronic briefs because the experience was very similar to having a paper brief.

The difficulty about using One Note was that I had to transport all of the documents – the documents effectively had to be electronically printed into the software, and while there are techniques you can use to do that more quickly, it was a little time-consuming,” Mr Thomson says.

Mr Thompson joined the WA Bar in 2001, five years after graduating from the University of Oxford with a Bachelor of Civil Law, and six years after being admitted to practice. His main areas of practice, commercial disputes especially for insolvency, shipping law or building and construction matters, are document-intensive.

He says life as an advocate has become much more convenient now that the days of hauling bundles of paper to court are over.

“Certainly most commercial disputes have very large volumes of documents and it becomes very difficult to physically carry around,” Mr Thomson says.

“I recently did a trial or four weeks in Adelaide and that was done much easier by doing things electronically. I took my computers with me, as opposed to having to lug 17 volumes of 12 bundles backwards and forwards between Perth and Adelaide.”

Reducing his reliance on paper has also altered what was once the logistical juggling of taking suitcases filled with briefs back and forth between his chambers and home. Nowadays, transporting content is as seamless as packing away a laptop and leaving the office.

“I have moved from having an office, which is significantly cluttered with paper, to one where I try to have almost no paper at all.”

Speaking about the receptivity to technology more broadly and the election by lawyers to run electronic trials (e-trials), Alain Musikanth suggests old habits die hard. Like Mr Thomson, the barrister is a member of Francis Burt Chambers in Perth. Mr Musikanth also served as the 2017 president of the WA Law Society.

During his stewardship of the law society, Mr Musikanth commissioned a report into the future of the legal profession. The report identifies technology as one of the greatest challenges facing the legal profession, acknowledging that many lawyers do appreciate the opportunities of the tech revolution. It goes on to note that some practitioners, however, are “still hesitant about how the use of technology will fit within traditional models”.

When asked why he thinks a large number of parties have not chosen to proceed with e-trials, Mr Musikanth says he believes people, clients and their lawyers, are stuck in old ways. Notwithstanding the fact that an official survey of the legal profession is yet to have been conducted on the subject, he says that there is no surge of litigants in e-trials because parties are simply used to doing things the way they have always been done.

“That’s just my own view on it – they are afraid to try something different. It requires buy-in from the solicitors, it requires buy-in from the barristers and obviously from the clients,” he says.

Brief encounters

Mr Thomson says that he prefers for solicitors to brief him electronically. This is typically done by receiving the electronic brief on a USB or accessing documents via email or secure portal. In his view, the portals used to share documents with counsel are comparable platforms between firms.

“My way of using the portals is to access the documents and save them on my computer, and then a separate disk that I can use, as opposed to going back to the portal and re-accessing the documents. That is also because the links on to those portals often expire after a period of time,” he says.

According to Mr Musikanth, software designed specifically for barristers is limited. Other than the practice management package SILQ, which streamlines accounting and conflict check processes, new ways to brief barristers tend to be the main innovation of interest.

“I know that some barristers, one in particular, trying to use a cloud briefing system, where he gets briefed over the cloud. It is just another way of doing old things. Instead of people sending hard copy briefs or a USB, the solicitor can put stuff up on a secure server, which can then be downloaded,” Mr Musikanth says.

While the Perth barrister says that receiving briefs in digital format is his preference, he adds that realistically some solicitors will resist doing things digitally and insist on sending paper briefs.

“Some solicitors will insist on sending you 25 lever arch files, which you can’t really conveniently cart around with you. I think it is just a matter of people doing what works for them but being dedicated as to the benefits of having as little paper around as possible,” he says.

Courting the digital realm: Why more barristers don’t build software

Security issues concerning the use of cloud computing and electronic document and records management systems (EDRMS) to exchange confidential information is an important aspect of this evolving area. While the discussion of protecting client information from data breaches is a popular topic among solicitors and law firms, they are just as relevant to members at the bar and the software infrastructure at their disposal.

The WA Law Society has developed its own ethical and practice guidelines to address security issues concerning cloud computing and practitioners who use it. The guidelines note that professional conduct issues can arise for a practitioner, specifically when relying on cloud computing software, and they are unable to comply with the requirement of “competent and diligent” delivery of legal services or have difficulty doing so.

Other potential pitfalls tied up with cloud computing include circumstances where a lawyer cannot guarantee they have not shared confidential client information without relevant authorisation.

Where comparable, these ethical boundaries may account for why few barristers have actively entered the software development space. Mr Thomson points to groups such as the legal publishing team behind not-for-profit BarNet JADE as a project that has worked well. The platform provides searchable electronic access to legal decisions.

“I have often wondered whether there could be developed some specific software that would be useful for barristers and there is some great examples of people who have done that in a different context. The BarNet JADE team have done a very good job in terms of developing a database for case law and legislation which is extremely good,” Mr Thomson says.

“And there are also certain chambers in Melbourne where they do have their own platforms for the way in which you can brief barristers but that also increases risk. If chambers offer a software platform which goes down at a critical time, that could jeopardise a barrister. Or if it gets hacked into, that could jeopardise a barrister as well.”

“That would be a risk then that’s worn by the chambers providing the platform. Whereas, at the moment, each barrister makes their own decision and obtains the platform from a commercial provider. If you have somebody like Microsoft or another service providing the relevant facility, the platform is much less likely to go down and there is no particular set of barristers that are bankrolling the risk of other barristers in the chambers,” he says.

The WA silk also suggests that another reason fewer barristers are actively involving themselves in developing innovation solutions is the speed at which technology evolves. When asked if he considers it useful for legally qualified professionals and barristers to be involved in developing legal software, Mr Thomson offers a pragmatic response: it is useful but not essential.

“I do think it is helpful if lawyers can be involved in developing technology that is used by lawyers but I do not know if it’s absolutely essential,” Mr Thomson says.

“It seems to me that questions of confidentiality are certainly much global in all sorts of different areas of commerce and use of technology.”

Listless for change

Late last year, taLaw introduced an alternative briefing model to the legal market in New South Wales. BarristerSELECT offers a free central service for solicitors to lodge the requirements of their matter, which gets dispatched to a group of chambers in Sydney. The product leans on the knowledge of a dedicated clerk to find the best barrister for a particular matter but, crucially, touts itself as being a time-saver for instructing solicitors.

In a state like NSW, where there are in excess of 80 barristers’ chambers, taLaw CEO Stephen Foley says solicitors can spend hours ringing around to try and counsel who may be available for their client.

“We are giving this time back, as well as access to a wide range of chambers, with our intuitive online form that takes a maximum of five minutes to complete,” he says.

“Good lists or good chambers will have barristers’ clerks that know their barristers very well and know who’s most suitable for the job. For the solicitor and barrister, it’s a bit like a matchmaking service, but it’s the clerk that is the hub in the middle that is the trusted adviser. It’s in their interest only to put the right barristers forward, because if they don’t it reflects on their chambers, so we’re leveraging the clerk as the [focal] point in this system.”

Chambers are charged $165 per successful engagement organised through the BarristerSELECT service. Mr Foley refers to the chambers connected to the network as “progressive chambers”.

“What we mean by progressive chambers is chambers that are willing to take on technology, and take on this type of technology to find the right barristers,” he says.

More direct access to advocates

With models for briefing barristers differing slightly between Australia’s jurisdictions, the use of platforms such as BarristerSELECT to disrupt established briefing processes can be a sensitive topic. A member from the Victorian Bar told Lawyers Weekly that its innovation and technology committee has spoken about the option of working with a similar provider to help facilitate the process of briefing of counsel. It is understood that the possibility in Victoria is still in its embryonic stages.

In Queensland, Level Twenty Seven Chambers was the first group of barristers in the state to adopt the chambers clerk model in 2014. Since launching, Level Twenty Seven claims to be “the largest barristers’ chambers in Brisbane” operating from a fixed address.

Then Hemmant’s List entered the foray in the Sunshine State, taking the chambers clerk model online in 2016. At the time of the list launch, chair Geoffrey Diehm QC told Lawyers Weekly that the clerk-led, e-chambers took a “modern approach to an old game”.

One of the primary goals of Hemmant’s List is to better facilitate an equitable briefing regime and the way that matters are referred to counsel in Queensland.

“Our aim was to untie the list from any physical set of chambers, which much better facilitates our objective of getting a group of people of high quality but of diversity, because chambers are tied together by other considerations that might mean [such diversity] is harder to achieve,” Mr Diehm says.

“The list hopes to principally do two things: one aim is to provide solicitors and clients with the facility by which they can make informed choices about who they wish to brief for a particular matter.

“And then from the barrister’s perspective, it is an important service for providing professional development, where the clerk is able to assist the individual barristers in progressing their careers and developing their practice into the client that they hope to have,” he says.

Mr Thomson does not consider these new ways to connect solicitors with lawyers as a poisoned chalice for physical chambers. This is because the purpose of a chamber of barristers is to promote a culture of collaboration and support, and this need will not diminish with new and more efficient ways of briefing counsel. He suggests that it is going a step too far to suggest that these technologies and tools will lead to a future where only virtual chambers will exist.

“It is necessary for barristers to practice in a set of chambers, typically speaking. The purpose of chambers is not simply the paying of rent together but it is also to advise each other, to have professional interactions and to support each other ethically as well. I do not think those things are going to necessarily be provided electronically. But I do think that the electronic delivery of material will facilitate streamlining of the way chambers operate quite significantly,” Mr Thomson says.

Ranking lawyers with analytics

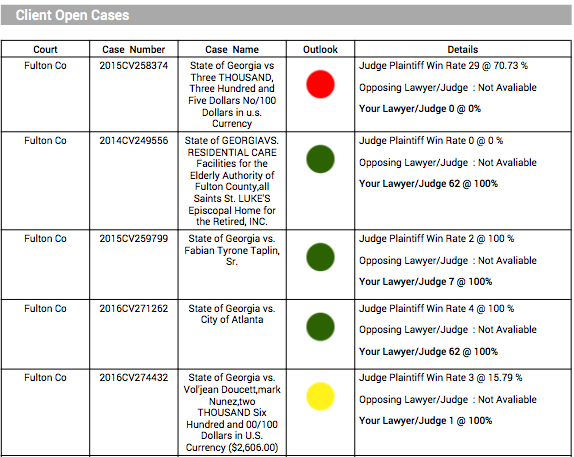

Just as Mr Thomson cycles through the ways technology has changed his practice, the silk stops abruptly and mentions a new product marketing itself as a tool for lawyers that also provides data to help litigants. Opening up the Litimetrics portal from his browser, he recites what information the so-called legal tech platform generates for the search entry ‘Joshua Thomson SC’.

“If I pay money it will tell me who my instructing firms primarily are, representative cases I have carried out and so forth,” he says.

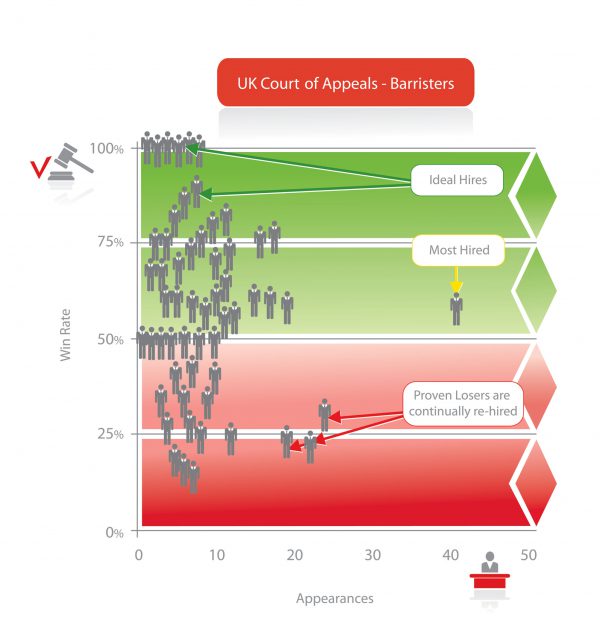

The engine claims to provide credible information to assist clients plan for litigation by summarising the experience of different legal practitioners in Australia. Using learning models based on recent advances in natural language processing, Litimetrics will mine and translate available data. The insights which can be accessed from the platform include information such as a practitioner’s main area of expertise, average case duration, success rates and settlement figures.

“It says ‘Joshua’s primary areas of practice appear to be constitutional law, corporations and associations, private international law, costs and contract…’ And it says that I was called to the bar 16 years ago.

“This is just another example of the way in which people are using technology to assess barristers and cases,” Mr Thomson says.

The Litimetrics’ website specifies that as a “provider of information about matters of public importance”, it will consider taking down profiles in exceptional circumstances only.

Similar data-driven platforms that offer performance metrics for lawyers, like US-based legal analytics firm Premonition, have already captured the full archive of court records in the Australian market. It is understood that the Victorian Bar is cautiously observing how these platforms evolve.

When asked about how much stock rankings of this kind should be given, Mr Thomson said advocates, especially senior counsel, are often engaged for the tactical advantages they can offer. He underscored the fact if a case was especially difficult, losing may not be a bad outcome

“If you have a senior counsel involved, they will make sure to take advantage of every point that might arise and you might actually get them to come up with a good outcome,” Mr Thomson says.

“That doesn’t mean that if they lose, they have run a bad case. It means that the case may have been a very difficult one in any event and the client’s trying to maximise the potential of a good outcome.”

Bench pressing for paperless trials

It took three years to complete WA’s new David Malcolm Justice Centre, located on the corner of Barrack Street and St George’s Terrace. Home to 33 storeys comprising a civil courthouse, judicial chambers for the WA Supreme Court, the Supreme Court registry and offices for the Attorney-General and Treasurer, the facility is now complete.

According to Mr Musikanth and Mr Thomson, the court is a leading example of state-of-the-art facilities which can accommodate e-trials and other electronic processes during court proceedings.

“The brand-new Supreme Court facilities in WA are very well fitted-out for electronic trials and/or the display of electronic materials,” Mr Thomson says.

Mr Musikanth adds that in WA, facilities to conduct e-trials have been around for over two decades. The improved fit-out in the Supreme Court building offers even more sophisticated technology to conduct paperless trials, he says.

“Certainly the facilities are there for any practitioners wishing to use them. There are enormous advantages to using them.

“Instead of going to court with your trolley, you make sure that everything is uploaded onto the system. You do not have a paper trial bundle, you have an electronic trial bundle, and everyone has access to the bundle on their screens,” he says.

Mr Thomson’s experience of how technology is used in the courtroom is varied. Overall, he reports his experience as a positive one. He says that in a recent matter before the Federal Court in Adelaide was able to conduct a case that involved using electronic spread sheets and A3-sized documents during cross examination. Modern facilities will also accommodate for split screens to project two different pages in the courtroom at once.

“You can identify the relevant spreadsheet, and electronically it is projected on to a screen. Then you can manoeuvre the witness through several cells in the spreadsheet so the cross examination can occur by reference to the particular cells in the spreadsheet.

“The judge is able to follow the cross examination, it’s recorded on the transcript by reference to the cell numbers and everyone can see it on the screen in front of them,” Mr Thomson says.

“Obviously it varies between different judges but I have had generally positive experiences in the courtroom,” he adds.

From 1 March 2018, there will be compulsory e-filing for documents relating to General Division civil matters that are lodged in the WA Supreme Court and district courts. The requirement will apply to solicitors on the record and government, with no confirmation as yet about whether the compulsory rule also applies to self-represented litigants.

“Making e-filing compulsory could end up encouraging e-trials,” Mr Muskanth says.

“Once that is in, it may have the effect of making people realise that it is actually quite convenient having everything set up electronically and maybe we should start using the electronic trial rather than printing all our paper out.”

In November, NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman announced that the Land and Environment Court would begin a trial of paperless hearings, with all evidence to be stored on USB and projected on to walls. Justice Brian Preston, chief judge of the NSW Land and Environment Court, said at the time that there was a strong likelihood paperless trials would become more common in lengthy civil matters.

“Paperless trials will only account for a minority of hearings in the Land and Environment Court this year, but they could quickly become the norm for lengthy civil matters as the legal profession adjusts to the technology and realises the benefits,” Justice Preston says.

By the end of 2017, five hearings had been scheduled in the NSW Land and Environment Court to consider electronic evidence and without using a single sheet of paper.