In Discussion With … Professor Gillian Hadfield, University of Southern California

In Discussion With … Professor Gillian Hadfield, University of Southern California

We were thrilled at the Premonition Podcast to be joined by Professor Gillian Hadfield, author of “Rules for a Flat World : How to reinvent Law”.

Gillian is an eminent legal academic and thought leader. She is both Professor of Law and Economics at The University of Southern California.

This article is taken from the transcript of that podcast conversation, where we discuss Rules for a Flat World, Global Legal Hackathons, Definitions of Quality in Law and the Future of Metric Based Hiring.

The Premonition Podcast

Andrew Weaver: It’s a great pleasure and privilege to welcome to The Premonition Podcast, Professor Gillian Hadfield.

Gillian Hadfield: Hi there

Andrew Weaver: Are you in downtown Los Angeles at the moment?

Gillian H.: I am indeed, I am indeed.

Andrew Weaver: The wonders of Skype. Now, I’ve just been watching a programme about Magna Carta, over here in England, and that leads me nicely into the fact that Gillian, you published a book last year called Rules for a Flat World, which, if I’m right in describing, was about why humans invented law, and how to reinvent law for a complex global economy. Give me a little background to why you did the book, the ambition of it, and perhaps also a reflection now we’re a year on as to the reaction. Things that have evolved since you wrote the book?

Gillian H.: The book is a product of thinking about how well our legal systems are or are not working over a long period of time, which actually has its roots in personal experiences in family law. Too expensive, not really addressing problems, creating more problems than it seemed to solve, which really snowballed into talking to general counsel in our biggest companies, and people trying to promote economic development around the globe. The thing I discovered through that process was that everybody really had a similar set of complaints about how well our legal systems work. They’re too expensive, they’re too complex, and really, fundamentally, not solving the problems that we need. I started thinking about these problems, my training is as an economist, thinking about, okay, this is a really fundamental piece of the way societies and fundamentally economies work, so what’s going on? Why are they not working very well?

That set up a line of research, and at the end of all that, what I end up with is wow, we’re at a really important time in the history of human societies. Things are rapidly changing and this fundamental, what I call legal infrastructure, is really not working very well. We need to be working fast to change that. I’d been talking to lawyers about that for a long time and the book was really born from the feeling that it was really important to get this message out to all the people in the world, people, businesses, governments, and so on, that depend on the quality of our legal infrastructure to say, hey folks, something really important is going on here. We all need to be focused on this. Part of the message was, don’t wait for lawyers to fix it because if there’s not pressure from the people who use law to change it, it’s probably not going to change, at least, certainly not fast enough.

Andrew Weaver: The book covers the fact that this is not just about legal tech, not about AI and Blockchain, this is also about the people that don’t actually have any access, which essentially is pretty much still half the world.

Gillian H.: That’s correct. It really runs the gamut, it’s from the ordinary person with a housing problem or a family or eviction problem through our large corporations, global corporations. In the advanced world, the poor and developing world, it just cuts across the board. You’d asked me about how things have developed over the time since I’d written it. You know, I was very tentative to try and to say part of the story in the book is to present sort of the evolution of law. Where has law evolved from? From our earliest societies. It’s just fundamental, that human societies need rules that people rely on and trust to organise their relationships. Those have to become more complex as societies become more complex.

I didn’t want it to be just about the latest, greatest, what’s happening in tech right now, but I will say that that’s probably the biggest change since the book was finished in draught in 2016 and then released the end of 2016 to 2017. I’ve got a few paragraphs about Blockchain, that’s moving much faster than I expected. There’s a paragraph or two about Brexit and the election of Trump, obviously, that’s just been transformative and I think that has its roots as well in struggles with technology and groups. How do they feel about … Are they represented in a way in which rules are made. So, I’d say that all of that, but that’s part of just being in this very, very fast moving environment. The basic message is still the same. Maybe I’m a little bit more optimistic we’ll get there sooner. There’s certainly more interest than there has been, historically.

Andrew Weaver: Well, that’s great. I think one of the interesting points … I mean, there’s so much we could talk about that your book covers. One of the points I found quite interesting, was the issue, the challenges around the world and there are many and varied, obviously, that we all know about instantly. Fundamentally, the legal infrastructure isn’t right, you know? We’ve got a major problem with all of those challenges and I think it was a really interesting point, although on a wider perspective. Because this, you know, Premonition is very much a legal tech company and this chat is going to be about legal tech, but for those of you interested in the wider perspective of law and how law matters, there is a wider perspective in the book that Gillian covers.

Just going back then to legal tech a little bit, Gillian, again, interested in your perspective on what drives it? Now, I think you have a view, don’t you, about the fact that clearly there needs to be diversity, there needs to be outsiders coming in, it needs to be about market energy. Just package in a few moments, if you would, your thoughts about what drives innovation and legal tech?

Gillian H.: I think the most important thing to recognise about innovation and legal tech is it’s happening in an environment that currently you might say has very little oxygen. Law is generally a very closed system, and I think that’s a critical reason we haven’t seen the level or rate of innovation to date that we absolutely need. Lawyers have structured a system that’s largely a monopoly to participate in. This is not true in the UK, but it is Canada and the US, and other parts of the world. You can’t get outside investment in legal tech initiatives. And, even in places that are more open, there’s a way in which law is seen as, you know, that’s what the lawyers do. The rest of us are kind of … We’ll do the deal, we’ll design the company, we’ll come up with the policy and we’ll throw it over the transom for the lawyers to do that magical stuff using whereas and heretofore and so on and so forth.

I do think that has meant that what we’ve largely got so far, is we’ve got efforts to build legal technology where there’s clearly money right now, so that a lot of that has been focused on this really tiny sliver. It’s a huge fraction of the actual revenues in the legal system … legal industry right now, but it’s really a tiny sliver of total legal work or potential demand. And, that’s the high-end corporate stuff that’s done by big law firms. I’d say the other thing that worries me about where legal tech is currently, is a lot of it is, understandably, focused on making the phenomenally complex world that lawyers have created, easier for lawyers to handle.

I love the fact that we’ve got AI that’s now able to review documents, tell you what’s in that NDA, manage documents. The real thing we should be aiming for is, why do we need a four page, seven page, ten page non-disclosure agreement that you need a machine to accurately read? I’m not sure that makes sense, or E-discovery, processing millions of documents, the fundamental question is why do we need millions of documents to resolve a dispute?

Andrew Weaver: Well, one of the things you said there, reminded me of Richard Susskind’s, one of my favourite Richard Susskind’s line was “It’s very difficult to go into a room full of millionaires and ask for them to change their business model.” So, it generally has to be outsiders, but also going to pick up on the question of why, because this was raised in an earlier Premonition Podcast, with Richard Tromans, here in the UK.

There’s a bit of an obsession with legal tech about who’s doing it and what’s being done and how it’s going to improve the lawyers’ lot, but there’s very rarely a question about why. I think also perhaps a question about what’s the impact for the consumer of legal services. What’s your view about those issues?

Gillian H.: Well, I think that’s the fundamental reason I say that yes we have more bubbling up in legal tech today, but I’m not yet seeing the kinds of transformational innovations that I think we need and can have. Those are the ones that make the legal world easier to navigate and more available to people than companies, than what we have now. The why is, why do you need law? You need law in order for people in communities, for people in businesses, for people around the globe to be able to work together, live together, move forward with investments, and joint ventures and so on. It’s not just to process documents and assess liability. I think there’s tremendous value there.

So, a really important thing I heard when I was preparing for the book, doing research for the book, went and talked to general counsel a number of, you know, big companies I was talking to. People at Cisco and at Google, I spoke with Kent Walker at Google. It was probably around in 2007, now it seems like ancient history, but I was just asking, what are the main issues you’re dealing with in terms of innovation, and how the legal system works and … It really emphasised, one, I have no way of figuring out what deals aren’t getting done because of what I’m dealing … you know, the documents involved, the delay involved, I can’t tell what’s happening in that sphere. I’ve a very hard time finding lawyers who understand I don’t want the 50-page legal memo. I need the advice that today, because I’m getting off the plane tomorrow to talk to a partner.

The capacity to help people navigate the legal system, I don’t see enough effort on that. I don’t see, how do we make it easier for people in businesses to evaluate their options. Run the scenarios, really understand what the difference is between taking that strategy and this strategy. I think there’s tremendous opportunity there that we’re not yet addressing and that’s largely because lawyers have not, I think, really taken to heart that that’s what their clients need and they’re looking for.

Andrew Weaver: Well, I’m going to come back to that point in a moment, Gillian, and the issue of quality. How people perceive quality in legal services in terms of the suppliers and the buyers. But just a quick point on transformational innovations, you were involved, I think, in the recent global legal hacks.

Gillian H.: Yes.

Andrew Weaver: An exciting weekend? Things that came out of that that you’re amazed by?

Gillian H.: I think what was so inspiring about the global legal hack fund was just the very fact that there were 40 groups in 40 cities, I think 21 countries around the world. That’s phenomenal to have that kind of energy on this topic and focused on this. When you scrolled through, and you see it’s in Johannesburg and Monash University in Australia, Ukraine, Los Angeles, London, Toronto. It was really very inspiring to do that, and to see the number of young people involved was really quite striking as well.

I put out a set of … I started tweeting a few weeks before the hackathon to say, let’s really start thinking, what are the problems worth solving here? I’ve watched a lot of these kinds of hackathons, or innovation challenges in law over the years, and I think it’s really important we focus on, what are the problems worth solving? Those ended up as the Hadfield Challenges, and got distributed. And the point there was, to say look, let’s not focus on how to make the really complex stuff more readable to lawyers. When people start thinking about innovation, the first thing they think about doing is, how can we process all of the material lawyers are producing that’s so hard to keep track of. Or how can we predict what lawyers and judges and existing systems are gonna do?

It’s all important, but you really have to peel down below the layer of that to say, what you’re really looking for is not going to be helpful to most, even small businesses, or even bigger businesses, to know what are all the terms in my contract. What they need to know is, how am gonna make sure my idea doesn’t get stolen? How can I be sure that my engineers are gonna be able to work on this project? How can I be sure that it’s worth the resources to commit to what the other side is looking for in this deal? Or evaluate liability, what are my alternatives?

I was really trying to prompt people to look below the surface of how to make our existing, overly complex, overly expensive system, and not just say, well let’s make that at least easier to read, and instead say no, can we produce something that’s more user-friendly, more effective. I always hold up my iPhone at some point to people, and say, look, this thing does really complex stuff, but the reason we love it is because it’s so intuitive to use, and that’s what I want for law.

Andrew Weaver: Did anything emerge from those hacks that particularly stood out for you?

Gillian H.: Well I saw some great stuff in the Los Angeles one. I was closely affiliated with that one of course. We had people working on a team, actually our winning team was students of mine who worked on developing expungement app for people in California who are now eligible to expunge marijuana records, which is a critical important thing to do for employment, for scholarships, for lots of reasons. Another team with a student of mine on it, that was working on actually developing for personal injury attorneys as a first use case, an online crowd sourcing substitute for focus grouping mock trials to evaluate cases and move into settlement, with a lovely ambition of taking that to much broader dispute resolution purposes. ‘Cause for a lot of people all they really need in their smaller disputes, is they just want a resolution. They want to be able to say, I got through a process, reasonable process, and I was in the right or I was in the wrong, and to be able to just evaluate that.

Another fantastic project, another USC student, with a contracting platform, a micro-contracting platform for, again, their initial use case was thinking about people in the creative industry. So lovely attention to, how do you produce something for a group of people where you don’t want to use the word contract, you don’t want to use terms of service, you just want to come up with a way for creative people to have something much more reliable and to actually get them out of the complexities of the state legal system.

So I saw some really terrific things emerging. I haven’t even had a chance to pour through all of them yet. I think they’re still organising them to go over the list, but I’m really looking forward to seeing the whole collection.

Andrew Weaver: There’s a great example of market energy at its best, isn’t it? People putting those kind of innovative ideas, and hopefully some of them will get funded and get some traction.

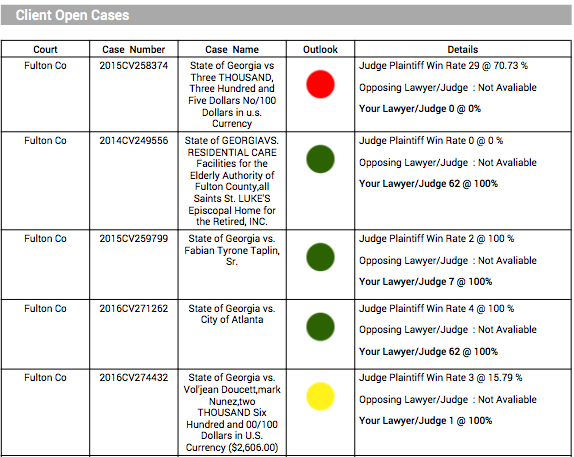

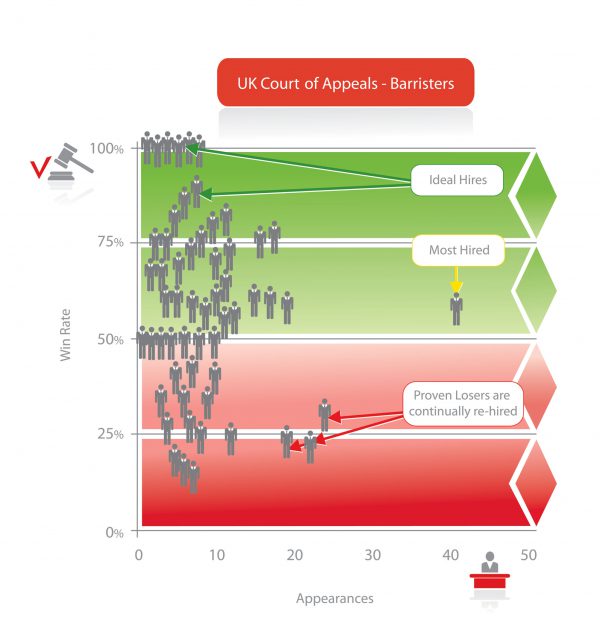

I’m gonna get into, if a may, to a couple of points that are particularly close to our hearts here at Premonition, and that’s the issue of quality. What I would call, what quality means to the suppliers, the lawyers in particular, and perhaps what quality should mean, to the market. From Premonition’s basis, we come from the position that we think there are some fantastic lawyers out there, but it’s sometimes very difficult to isolate who they might or might not be. Our platform is based on win/loss ratios. Give me a little explanation, because I know you’ve covered this on other forums, about the issue of quality and how it’s perhaps … Your challenge to lawyers is perhaps misunderstood about what that means.

Gillian H.: Yeah, so, lawyers don’t like it if you say we’ve got a problem with quality in the legal industry, because it sounds like you’re saying they don’t understand the things they’ve studied and worked at for a very long time. How to read cases, analyse cases, conduct litigation, draught a contract and so on.

In fact, I’d say, when we think about quality in that way, this is actually a well known difficulty. People will talk about it’s the gold plating problem. That lawyers are … They’re wonderfully smart and committed people and they are driven to do an excellent job. Identify every possible risk, evaluate all possible litigations strategies, think about all the things that might happen. The difficulty with that, I think it’s important to remember, as an economist talking, quality is about doing what the person who’s come to you for service needs you to do. And quality is the match between what they’re looking for and what they need and what you are supplying.

We also use quality more generally in other industries, to talk about differentiated quality. So, it’s true. The high-end BMW is a higher quality car than the Honda Civic or the Neo, or whatever. When we think about quality we’re thinking about how well are you serving a market, in fact a differentiated market. If we think about quality as the ability to write a perfect, from an academic perspective, brief or argument, then it’s like saying the whole world … You could only buy the top-end vehicle, and we’re not going to make those Fords, the lower-end Ford or whatever, I know Ford makes some very high-end cars as well. And we’re not gonna build buses. It’s important to remember quality is ultimately about what works, what produces value for the person who needs and buys these services.

Andrew Weaver: Looking at it from an economic perspective rather than an intellectual or cerebral perspective?

Gillian H.: Yes.

Andrew Weaver: But AI is what fascinates us in particular and I know that we have some common ground here, because you judged a AI versus lawyer challenge, as did we in the UK with a case prediction challenge, which found out to be more in favour of AI than lawyers. And you had a similar experience with NDAs recently.

Gillian H.: Yes, yes. So I had some input into the design of this study, this was done by LawGeex in Israel. This is an AI trained on NDAs as an initial use case. Presented a set of NDAs that hadn’t been seen before to the AI and then to a group of 20 lawyers, and compared the accuracy of the lawyers and the AIs. The overall result was the average lawyer was catching about 85% of the elements of the NDA, and the AI was getting about 95%. This is just saying yes, there is a non-compete in this document. Yes, there is an arbitration clause in this document. It’s not going further than that yet. So as good or better. But of course, massive time difference in how long it takes to accomplish that objective.

I think importantly, the humans were given their best shot at it in a set up like this, because in the real world, humans aren’t told, sit quietly in that room for as long as you like and do nothing except identify the provisions in this contract. Really nobody should be getting less than 100% on that, probably.

In the real world it’s part of a busy day, it’s sinking to the bottom, it’s taking two weeks before you get to it in the first place. There’s a quick scan on the bus home or something. I actually am hoping we’ll be able to, at some point, to run the testing in the wild. And watch, and laugh.

Andrew Weaver: I’d only saw the one over here, but it was run by a CaseCrunch and Premonition was one of the technical judges. The conclusion of it was that the accuracy rate with the AI was about 86% and the lawyers was about 62%. So there was quite a sharp difference between the two. From your perspective in the study you did, what do you see as the implications of those results and where it might go next?

Gillian H.: There’s a lot of things that come from it. One is, I think we’re a very short time away from, the best practise would be that you would have a machine read it, just to do this kind of identification. Precisely for the fact that you’re gonna get the same result every time, it’s gonna be reliably done. So I can imagine that becoming best practise pretty quickly.

I think it’s a demonstration also of, wow, you need a machine to read this stuff. Does that make sense? Because the whole function of a contract is to coordinate human beings and organisations in their activities. If they don’t understand what’s in their contract … If we piled so much complexity into our documents that you need a machine to reliably keep track of it, maybe that’s not performing the function.

I’d love to see the next step in AI, to figure out what you really need in there. Connect that up with, again, this is something I remember from Kent Walker telling me when I was interviewing him, he said, look we’ve signed millions of these things, and again, this is back in 2007. He said, in my 10 years at this I’ve yet to see a case where the result turned on the language of a non-disclosure agreement. So if that’s the case, we’re spending tonnes and tonnes and tonnes, and now developing AI, expensive AI to do something, and saying, but what real effect is it having? Is it really improving the capacity for people who want to share ideas and build businesses together, to do that. So I’d love to see it head in that direction. It’s not gonna put lawyers out of business, but maybe it’ll make us better at it.

Andrew Weaver: Maybe push them back towards doing biz market reasoning, which is what you want to pay for the value, but anyway.

I’m gonna ask you a final question. It’s a little bit Premonition based I guess. We’re finding a lot of interest coming from sectors like the insurance industry. They’re automating their claim and case analysis. They’re beginning to automate their lawyer shortness. How do think the market will manage the move from, what I can tell, relationship-based hiring to more metric-based hiring?

Gillian H.: I certainly think we’re headed in the direction of more metric-based hiring. I think we should be heading in that generally. We don’t have enough insight into transparency of … Come back to that word quality, outcomes, value, in law. I think this is a critical problem and you can see this throughout, whether it’s … That’s a reason we haven’t had enough innovation within, forget tech, let’s figure out a better way to serve our clients because there’s not enough transparency into the results and metrics. Certainly within the large legal departments, the shift to metrics has been pretty significant.

Same thing’s true with legal education and figuring out, how do we better train, certify, oversee, the people who are ultimately providing legal work and products. I do think that the fact that we are getting so much closer to being able to say, this is what works, and this doesn’t. This is worth it, and this is not. Very quickly you’re gonna say, do we have better case outcomes today with e-discovery and millions of documents, than we had in a world with paper where it was relatively limited what you could capture. I don’t think we’ve probably improved the quality of our dispute resolution. We’ve significantly increase the cost, but we probably have not increased the value that we’re producing.

I’d love to get more and more data out there about what our lawyers are able to do, what they’re doing, what they’re not doing, what they could do better, what clients really value, what makes a difference.

Andrew Weaver: Well on that grand note, from our perspective Gillian, I want to thank you again for giving us your time. Such an esteemed guest for our little fledgling podcast. I’m completely thrilled to have had you talk to us.

Gillian H.: Delighted to. Thanks so much, I really enjoyed it.