Fascinating Interview with Premonition CEO, Guy Kurlandski

Fascinating Interview with Premonition CEO, Guy Kurlandski

Our CEO Guy Kurlandski was recently involved in a fascinating podcast discussion about Premonition, Litigation Analytics and the enormous impact they are having on lawyer transparency, insurance risk assessment and potentially stock market movements.

The podcast is available here but, you can read an edited transcript of the interview below;

Andrew Weaver: My relationship with Premonition started at the end of 2015 when I recorded a podcast with Toby [Co-founder). Those were the very, very early days. A lot hashappened since then. Just give us a quick catch-up over the last 18 months. The progress you’ve made?

Guy Kurlandski: We’d been working at it for about 18 months previously, both Toby and myself. And funding the project ourselves, and the business. At that point we did a seed round. We raised some capital. The ambition was to put some towards developing the system further, and some towards marketing. We got a little bit carried away with developing the system, I must say, and kept building on the scale and size of the database that we draw from.

Originally, we never realised we’d actually have to build the database in the first place. We always assumed if we can build the machine learning application, and the AI, around what we need to get the results we want, we’ll be able to lease it. To licence it from one of the big players in the market, only to find that they don’t have enough data, and it’s not aggregated, and it’s not clean enough for our purpose. Not that it’s not available to us, it’s just, they don’t actually have it. So that became a big task in and of itself.

So today we’re sitting on the world’s largest litigation dataset. It’s very good to have that under our control, effectively. And we’ve been doing some licenced deals with some other companies that we thought we might be leasing the data from, ironically.

And then we’ve been developing all sorts of systems from the data, and that’s really where it starts getting very interesting. So we can ask some very specific questions.

Andrew Weaver: I saw you on another broadcast commenting that there are 17,000 lawyers in Dade county, alone, which is astonishing. 17,000 is the number of season ticket holders of my team at Nottingham Forest, it’s a fair amount of people.

Guy Kurlandski: It is.

Andrew Weaver: But within that 17,000, you can drill down into actual performance rather than necessarily anecdote and opinion about that particular lawyer.

Guy Kurlandski: There are a lot of lawyers in America. There’s something in the region of 1.25 million lawyers in America. There are other countries with a lot of lawyers, too. We’ve been approached by various businesses and companies in Brazil, and we’re trying to put a JV together for the Brazilian market. Brazil has a million lawyers, and an awful lot of cases. In fact, they’ve got about approximately one hundred million open cases at any point of time in Brazil. So that’s quite a daunting project, but at the same time, quite exciting. The value of each individual case there is much lower.

And so, the US is where both Toby and myself are living. You’re quite right. We’re British. We’re not used to the system, here. When we first moved here, it took a little bit of getting used to. You can be having what you would perceive to be a very small misunderstanding that, by European standards, or British standards, would be, “Let’s go have a cup of tea and work this out.” You haven’t even reached the point where you’re going to say, “Let’s call my lawyer and get him to write a letter.” You jump to that “Let’s have a cup of tea and work this out,” and you’re served. It’s really quite crazy from that point of view.

And then there’s a secondary market because of the “loser pays” rules in America, where you have a lot of lawyers that are geared toward contingency-type cases. They’re pulling cases from the average man on the street, let’s call it, where they see an opportunity to sue a wealthy business because the risk is so low. So what they’ll do, is they might file 100, 200, 300 cases a year, knowing that some will stick, and in some cases the insurance companies will just pay them off because of the nuisance factor. Otherwise, they’d be court-ordered, effectively, to defend themselves, and that could cost an awful lot of money.

Andrew Weaver: The volume and the litigious nature of the States may be far in excess of what we experience in the UK. But one consistency is the lack of transparency, which is at the core of what Premonition are doing.

What’s been the reaction from the legal community in terms of your arrival on the scene?

Guy Kurlandski: Well I didn’t fully answer your question, and I’m going to go back to that one. So, 1.25 million lawyers. 120,000, give or take, in the state of Florida. I’m based in Miami, and Miami is a city in a county called Miami-Dade. The county has, obviously, a much bigger population than just the city itself.

Now, Miami-Dade is part of the tri-county area. So it’s the most populous part of Florida, the Three Counties. Palm Beach, Broward, and Miami-Dade. But just imagine … Just in Miami-Dade, there are 170,000 attorneys, as you quite rightly said. And it doesn’t matter how well-informed you may think you are, doesn’t matter if you’ve been working in the legal industry for years. You can’t possibly know or second guess the relationships between attorneys and judges. And I’m not talking about the personal relationships, or anything shady. Just the relationships. How they resonate. How they operate in that judge’s courtroom.

It’s very opaque. I mean, the best we have until we came along was peer review, where you’re relying on someone’s opinion. And often systems that can be bought or manipulated, offer award schemes, and … I’m not going to name them, exactly. But there’re all sorts of books and products out there. “500 Top Attorneys”, “Very Super Attorneys”. And you go to these laywers’ offices and everything’s a perception, right? You go to the white-shoe firms, they’ve got nicer offices. And they’re in big towers, and they have beautiful artwork, and they take you for nice lunches. Doesn’t mean you’re getting the right attorney for your case. And time and time that’s been proven.

In fact, our data’s shown, through personal examples that both Toby and me have had, that sometimes the thing that is perceived to be good information to make a judgement actually can fire totally against you. I.e., “Oh, look at that. That attorney must be good. He works in a reputable firm with a good reputation, and he lives next door to the judge. Let’s hire him.” Whereas, in actual fact, they really don’t like each other, and it shows in the courtroom. But it can be completely the other way. They really do like each other. And not only do they live next door to each other, they attorney’s married to the judge’s daughter, and they still get on, and go every weekend and play golf together. But just with that reason, that they’re worried someone might be looking, the judge always rules against his son-in-law.

Having information is dangerous if you don’t have all the information, because you can make assumptions that seem very obvious. And when you’ve got so much at stake … I can’t understand how anyone can make those assumptions when there is a better way. And I believe we’ve built a better way, and that is we look at all the cases, and we look at all the data.

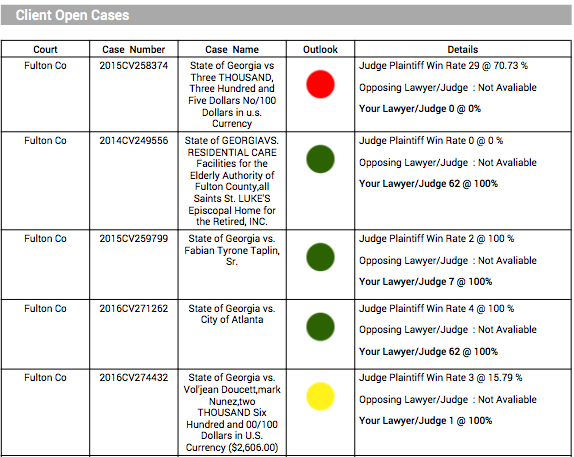

So we can actually … We don’t have to go and look at at attorney and say, “Will this attorney be any good in front of that judge,” which we can do. But we can rather engineer it differently. We can say, “Right. I’ve got a specific type of case, and I know … I’m in the defence position, and it’s going in front of this judge on the circuit.” But that type of case, who has the best performance? Who has the best? Who gets it done in the shortest time frames, et cetera, et cetera?

And work it out, as I say, in reverse. Pick out a list of the top five and top ten. And I always think about it … You said at the beginning of the podcast you’re a simple man. I always like to think … I’m a simple man, too. I don’t like to overcomplicate things where it’s not necessary. So my perspective is it’s a bit like GPS. If I put coordinates in my GPS, an address, and it takes me to a house, and there’s one doorbell, it’s really easy. But if it takes me to an apartment building, because that’s the address, and I still need to look on the list for the name of the person I’m going to see, I’ll manage perfectly well. That’s really what we’re offering.

It’s like a GPS system. It’s going to get you to the building. The one thing you know is there’ll be five or ten apartments in the building, and they’re all top performers. Now you can do the rest of the due diligence, yourself. Go find out if there’re any conflicts. Can you hire that person? Are the attorneys people you could work with? What are their rates? But does it matter if you pick number three, or seven? Not really. And I think a client can make their own assumptions on that premise. In some cases, number one will be such an outlier that … Well, if there’s no conflict, but you don’t like them and they’re quite expensive, it might still be worth hiring them. But that’s a personal choice. But imagine you’re down to ten from 17,000.

Andrew Weaver: It’s powerful stuff and an interesting point you raised, there, is a lot of people will say, “I like to have chemistry with a lawyer, and I like to be able to get on with them.” And, of course, you’re not eliminating that. That’s a crucial part of selection. But now, alongside that, importantly, you’re actually finding out whether they’re any good. And I think that’s where it’s powerful.

The other area I like is that classic situation where you are with a firm, and they say, “Well, sorry, but Mr. Smith can’t do it however, Mr. Bloggs is tremendously available.” But there’s a reason he’s available, he may not be any good.

But, again, the ability to dissect within a firm who is good and bad is very powerful, particularly for volume instructors of lawyers, I would’ve thought.

Guy Kurlandski: Yes. Very much so. I mean, that goes on very often. It’s sold very much as a relationship business. And, I mean, personally, I’ve got relationships with my family and with my friends, and I have attorneys who are in that second group. Actually, in both groups. Family and friends. Doesn’t mean I’m going to instruct them.

Andrew Weaver: Not now you’ve got the data.

Guy Kurlandski: No. And it doesn’t mean that they’re not good attorneys. But they might not be the right attorney. See, I can have that comfort. I’ve got a good friend, who actually happens to live next door to me. And he is a good attorney. But he’s not a good attorney for everything, and he’s not a good attorney for everyone. So the natural thing to do, if I had a legal problem, would be to knock on his door and say, “I’ve got a legal problem. Help me.” That’s what most people do. I wouldn’t do that. I’m going to run the data, and … If it fits. But, otherwise, no. And you’re quite right. That’s why I don’t get too stuck on that whole “You need to have a good relationship” thing. Yes, you have to have a working relationship. you’re sick and you need surgery, you don’t have to love your surgeon. You just need to know your surgeon can fix you.

Andrew Weaver: That’s for sure. You don’t need to go play golf with him. But going back to the question about any the pushback from lawyers and from the legal community. What’s been the reaction?

Guy Kurlandski: So, I have to say, at the very beginning, Toby and me sort of sat down, said, “This is going to be really powerful. We’re going to have a lot of pushback. There’re going to be some people that are really, really upset with us. We’re in America, so we’re going to get sued a lot.” In reality, we have had pushback, but it hasn’t been anywhere near as aggressive as we imagined. I think, partially … This is an assumption, and I don’t like making assumptions. But it’s somewhat of an educated assumption. I think that, partially, it’s because our data is real. It’s pulled from public data. We’re not manipulating it. We don’t let anybody influence it. You can’t buy better data. And the attorneys that maybe don’t like it are very aware of that. So it’s very hard to argue against really, clearly, the truth.

I just want to say, this is like you’re caught speeding. And the cop pulled you over. And he’d say, “you were doing 90 miles an hour.” “No I wasn’t.” But he holds up a radar gun. You can’t argue. There’s the radar gun. You could be a bit facetious and start saying, “Well, it’s not calibrated.” But, chances are, it’s calibrated. It shows a speed, that’s what you were doing. So we’re getting less kickback from that perspective. But remember, we didn’t build this tool, Andrew, for the lawyers. We built this tool for the clients of the lawyers.

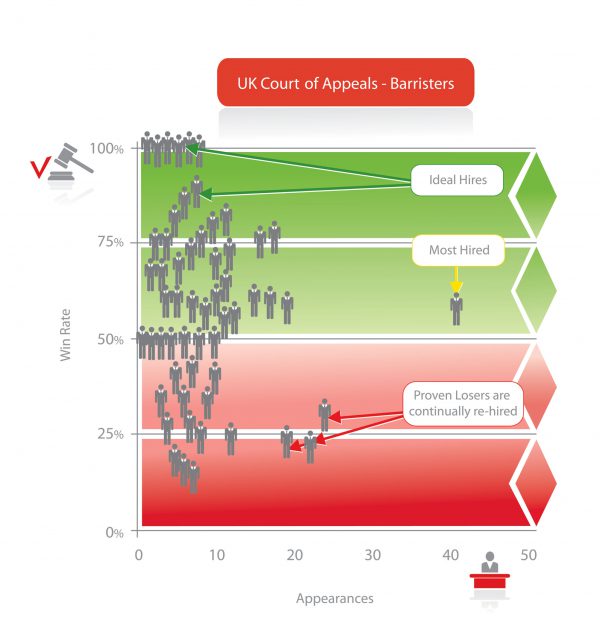

Andrew Weaver: Not wearing a lawyer’s hat, but maybe giving one of the arguments that they might come back with is saying, “Well, I only take on tricky cases. Judging me on my win and loss rate is pointless, because I actually go for the really difficult ones, and therefore my percentage is always going to be lower.” How do you respond to that?

Guy Kurlandski: Well, again, we break down the complexity of the cases by the information we have. And quite often, that is contained within the type of court the case is being held in, and the type of case it is. So a good example is Queen’s Counsel in the UK. We have the UK data. Queen’s Counsel, in the high court. We’re looking at all the barristers in there. And all the cases are complex cases. That’s why they’re there. The answer’s quite simply in there. You’ve got cab-rank rule, well, let’s add that into play in the UK. So, are can they really argue to the fact that they’ve only taken the hardest cases? No, they’re taking cases that go into that court system, and they need to take them in order because of the cab-rank rule. I don’t think that really plays.

The other thing is, this is en masse. So if you look at an attorney that’s doing complex business cases in the US in a certain federal court, they’re all hard. And you can compare them to their peers. In some cases, you can even compare them very, very well, because they involve contractual matters that are very similar for the same client in different courts.

Andrew Weaver: And you are spreading around the world at quite a rate. India, Canada, Australia, Holland, UK, US. And you just mentioned potentially Brazil or South America?

Guy Kurlandski: Brazil, potentially. European high courts. Maybe … I mean, we’re talking, as well, with the Ukraine. We’re talking with Colombia, as well.

Andrew Weaver: Have there been noticeable cultural different reactions to it? Or is it pretty consistently the same response?

Guy Kurlandski: Maybe a little bit. I think it depends, it really … Yeah. You’re quite right. It depends on the country. We haven’t got far enough with India to see any pushback from law firms. We have a lot of support from a law firm, and actually from the ex-Chief Justice of India, Ram Jethmalani. Brazil, Colombia, likewise. Their legal industry seems to like it very much, because they’re the people that are actually inviting us in.

Which is quite interesting. Because they want to see more transparency and reform. They’re desperate for it. The US … I mean, you get some pushback at the end of the day, but we’re also finding use and purpose within the law firms, too. As I say, though, that’s not our primary market. We’ve never built this to be another tool that the 1.2 million lawyers will use, though they will, I’m sure, in due course. It’s rather the other 350 million people that are their clients.

Andrew Weaver: I noticed that something like 19 out of 25 global law firms use Premonition as part of the hiring process, which makes sense. But that’s an interesting use of the process by law firms.

Guy Kurlandski: It is. We had a sort of big take up by a recruitment element. They were looking at it when they were looking at placing higher level attorneys into big law firms.

I think if a partnership is looking for another attorney to join their group, generally it’s because someone has left, unfortunately, retired or passed. And there’s a hole. So they’ll be looking for a specific purpose for that person. And that will grow.

Andrew Weaver: Talking about growing and broadening the offer. The world of insurance. The world of risk-assessment. Must be a growth area for you. Are you making movements in that space?

Guy Kurlandski: Very, very much so. For us, that’s our biggest market. We’ll start at the beginning, the obvious reason, is that most people, certainly in the states, have some sort of insurance policy that will pay for a case, if they get sued. They have some sort of liability somewhere along the way. So the majority of cases in the US are actually paid for by insurance companies. And very often, the insurance companies are partly responsible for actually hiring the attorneys to represent, or agreeing on the attorneys that are hired. That’s a big market for us.

The obvious is that, in a claims department in an insurance company, they look at the total cost of the case. So whereas we have attorneys that are looking at things from a more philosophical point of view, insurance companies are looking at things from an actuarial point of view. It’s dollars and cents. So they have systems in place. There are two large companies that provide the bulk of the insurance world with numbers, if you like, when that case comes in. So they’ll have a case. They’ll look at all sorts of parameters and profiles about zip code, the parties involves, the average payout, et cetera. And they’ll assign a number to it, not forgetting the “loser pays” rule.

So if they, for want of a better term, an ambulance-chaser attorney sues a store group for a slip and fall in the store, they’ll be looking at all of those parameters, but they do need to defend themselves at this point. So they might say, “Right. Well, it’s going to cost X, but it’s going to cost something to defend ourselves. We can get out of this in that zip code based on the demographics, and all the other variables at best. Let’s try and get out of it before we run the case.”

So it’s very much driven by numbers. Now, in that, they don’t actually have a specific number for the specific attorney being appointed to the case. In some cases, it’s more sophisticated, in some cases less. But as a general rule of thumb, they’ll just say, “Right. In that county, we generally pay out for that case $35,000. Let’s try and offer them $25,000 to go away.” Or whatever the case may be.

If we can come in and say, “Right,” because you’re giving it to this insurance defence firm, and it’s a big firm. There’s 600 attorneys in there. But the odds of the right attorney running the case is very low, so you’re getting this average outcome, if you run it, of 40%. And, actually, if we specified that attorneys could run that case and get you 80% success rate, this could change the total number equation completely. There’s a really nice part to that. If the total cost of cases, when claims go in, goes down, insurance premiums can go down. And we all benefit from that one.

Andrew Weaver: I’m going to take you into the future, partly because you got me excited before we started recording, and I actually had to stop you from going too deep into this subject, because it’s fascinating. Stock market predictions. The impact of this kind of data, potentially, on stock market movements. Just go through it, if you wouldn’t mind, again. Just a little bit of your thinking on this and the impact it could have.

Guy Kurlandski: This was one of those little wild ones that sort of popped up, because we’ve got this huge database, right? What other piece of interesting data can we cut out of it? And we’re always coming up with new ideas. So there are lots of companies out there, and data, data company, and various things, running data to try and help the financial market. But the realisation that the data we have, they don’t have, made us think about, “Well, what can we do with our data?” And what was noticeable is that when you look on quarterly returns of companies and their annuals on the stock exchange, very rarely is there a lot of information about pending litigation. Both the plaintiff and defendant.

Now, it’s not true that there isn’t a lot of information about cases. It depends on the case. But there’s very little often in those reports. Now, the second part is that … If it’s a big type of company that’s having a massive IP case, a pharmaceutical, or Apple vs. Samsung, or whatever it might be. And it’s a massive IP case. It could be worth hundreds of millions of dollars. Well, we all know we can read a thousand opinions by day’s end. The case was filed. They’re talking about it. You can’t actually get away from reading about it. And generally, the opinions … There’s some validity in those opinions, let’s say. And that’s one area.

But there are many, many companies that have small litigation matters, or relatively small litigation matters, two, three hundred thousand to a million five in size. The smaller cases that are just sort of flowing under the radar. No one’s paying attention to them, individually. We found there’s certain companies that have lots of employment issues. Union-based companies. Companies with lots of staff, where there’s lots situations. All sorts of things, where they may have, because of the scale of the companies and the size of America, they may have, literally, 500, 1,000, 2,000, we’re even seen, open cases. When you have 2,000 open cases and the average value of the case is $500,000 to $1,000,000, it can make a really significant difference to the numbers of the business.

Now, you can generally assume that they’re going to come through in reasonably the same speed and form. So maybe they take, on average, three years to pass through, and they’re at 80 cases, or 200 cases, whatever it might be a month. But it doesn’t work like that. What happens is that you’ll get troughs. More cases, and you’ll get troughs of cases closing. And that’s what we can look at. So we can start looking at businesses that have these smaller cases that no one else really valued into the market. And what we can do is, we can stat making predictions based on case durations. Based on who is running the case. Which firm? Which attorney? The case type? In front of what judge? That judge generally operates for that case type in that court. How quickly the attorney operates. And we can look at their historical outcome rate, and we can do it en masse.

Now, what that means in round terms, is we might see a spike or a trough coming the next quarter, the quarter after that. And that’s a really powerful piece of information. We’ve tested it. We got .7 correlation, which is a very high correlation. And we’re actually running a small incubator fund, now, too, so put it to the next level, and take it to the next level, before we market the data to the financial world. Though we’re ready now. I believe we’re ready. We’ve got enough cases to prove the model really works.

Is it viable on its own? Probably not. But it can be used in conjunction with the other data pillars that traders would be using. And it could be really valuable. So they may see that this share has a very positive outlook for the next year, and we might have some information that shows … Then, well, actually, by the end of the year, there’s a really negative amount of cases coming in. Or vice versa. I think it’s very valuable.

Andrew Weaver: You mentioned an incubator fund. Is that up and running?

Guy Kurlandski: That’s up and running. We’re placing some trade. It’s one of those things, again, going back to your line, my line too. I’m a simple man. I wouldn’t expect somebody to do something I wouldn’t be willing to do myself. And that applies to our business, as well. So we put our money where out mouth is. We felt we need to actually put some money into a fund and actually run our data and make some actual share purchases based upon our data, and see what happens. So that if we go out to that bigger world of traders, and hedge funds, and various guys, and say, “This is really interesting data. Do you want to buy it?” We can actually say, “And here’s our track record for the last X amount of time,” and “We’ve made trades, and this is what we’ve done. This is what we’ve achieved.”

Andrew Weaver: Your vision for Premonition, three to five year’s time … Where would you like it to be? What would you like it to be doing and achieving, sort of thing?

Guy Kurlandski: Three to five year’s time, I’d like to see that we are a very instrumental player in the way the majority of attorneys are being hired. I think it makes for a fairer place. A transparent world, and not an opaque world. And there’s so many benefits that come from that. So the insurance world will benefit. Businesses will benefit from the use of making informed decisions. In some cases, small mom and pop businesses are hiring an attorney that charges them an awful amount of money. And for no reason, they lose everything they have and everything they’ve worked for, just because they have the wrong representation. This needs to change. So I hope that in three to five years, we go from being a business that’s being piloted and used by bigger businesses and insurance companies to being a very mainstream, “You have a legal problem, you run the data through Premonition before you do anything.”

Andrew Weaver: And Litigas.com is the first step towards that?

Guy Kurlandski: Litigas is consumer-facing, and we have Premonition tool that’s B2B facing. And they are law firms that rely upon the Premonition data to assign the attorneys. So you don’t have to then come to Premonition to get the information, you go to the law firms. So if you are that mom and pop store, you go to the law firm of Litigas, and they will ensure that you have a top ten attorney for your case.

Andrew Weaver: Well, I shall put those links on the podcast. It sounds like a no-brainer to me, Guy, and for two simple men, I think, and I hope we’ve explained the Premonition proposition fairly well. Thank you so much for joining us.

Guy Kurlandski: If it can’t be explained simply, there’s normally a problem or something wrong with the theory.

Andrew Weaver: Opaque is what the lawyers have liked and thrived on for generations. Thanks for joining us.