Legal analytics: Where are the data scientists?

Legal analytics: Where are the data scientists?

What is it that lawyers do?

“They help people navigate complexity and manage enterprise legal risk,” according to Daniel Katz, an expert on emerging legal technology and one of the speakers at a conference put on by LegalX and Thomson Reuters in Toronto this week.

A follow-up question to that is, how does one put a dollar figure on a lawyer’s work, other than relying on the billable hour? Unfortunately for clients, it’s the complex nature of legal services that makes it so hard to ascribe value to what lawyers do. For the unsophisticated client in particular, it’s almost impossible to separate the wheat from the chaff.

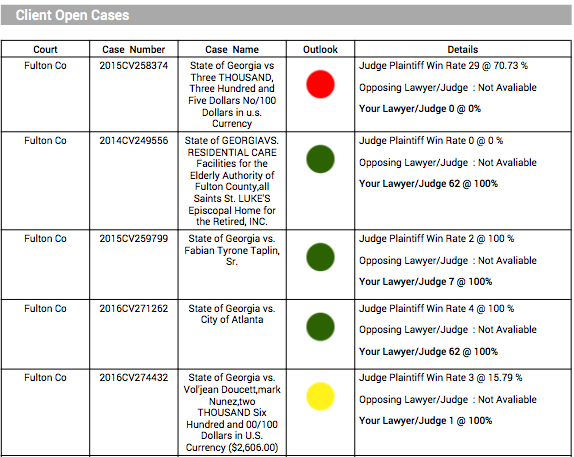

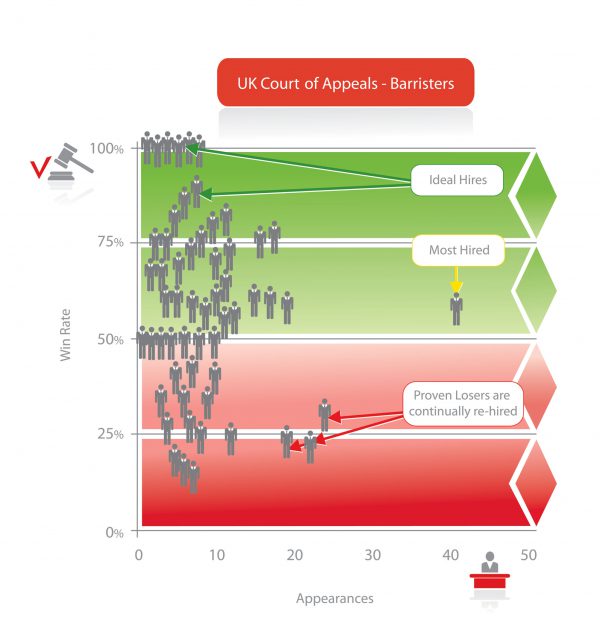

But in the age of data analytics, that is all quickly changing. There are several tools already available on the market that help companies control their legal spend. Last year, AIG launched a legal consulting company that harnesses the insurer’s own internal data to sell it to corporate clients to help them set competitive pricing for legal services. Increasingly, law departments are looking at past case performance to select law firms and lawyers, says Toby Unwin, co-founder of Premonition LLC, a Florida outfit that uses artificial intelligence to determine the effectiveness of trial lawyers.

If outsiders can measure the value of legal work, you’d think law firms would be scrambling to hire armies of data scientists to help them make sense of everything. By benchmarking their own lawyers against the industry, they could be proactive about costing their work.

But they are few and far between in law firms, says Jennifer Roberts, a senior strategic analyst at Intapp, which is curious considering how in demand data scientists are these days.

Part of the reason is traditional law firm hierarchy. Lawyers are typically reluctant to share ownership of initiatives with tech experts, data scientists and other professionals, says David Curle, director of market intelligence at Thomson Reuters Legal.

Fear of the truth is another likely barrier. A commitment to metrics is a tough sell in a profession with an in-built aversion to admitting error.

And for lawyers, who suffer from “numerophobia,” the very idea of going down the rabbit hole of data analytics can be daunting. Get over it, says Katz. “Embrace legal analytics to help you do your job better.”

Katz, an associate professor at Chicago Kent College of Law, is quick to remind lawyers that finance lies at the core of much of what they do. The value proposition for lawyers is in putting a price on risk. “A mediocre lawyer finds risk; a great lawyer helps you price risk,” says Katz. That ability to price risk will be valued all the more in the coming years as see large elements of the legal industry become “financialized.”

Curle makes a similar point. So far, he says, legal data analytics has mostly centered around litigation, primarily by shedding light on patterns about past litigation. “We need data to identify client risks before litigation,” he says.

It’s for these reasons that every organization in law needs to think about data as an asset and work on a data strategy, says Katz.

The first step, according to Curle is process mapping to allow for data analysis of how lawyers are performing work. He argues that innovation in law is as much about process change management and building partnerships with allied professionals – his preferred term for “non-lawyers” – as it is about technology.

Katz also views this step as critical to the legal industry’s ability to change. “Then you’ve got to clean up your own stuff,” Katz says, before you can design ways for the data to behave well.

This is where the argument circles back to the why firms need to get real about bringing in non-lawyer experts in-house to help them catch up in a discipline that is evolving quickly.

Law firms need to jump in or risk being left behind, and according to Curle that means giving them a stake in the firm’s success and treating them as equals. “Data scientists can go to a law firm,” he says. “Or they can go to a start-up where they can share in profits.”