Premonition for Law Enforcement

Premonition for Law Enforcement

Premonition is the closest thing there is to Minority Report.

It monitors courts in real time for persons of interest.

Its artificial intelligence system spots trends and outliers before human agents are aware.

Arik Arad, Former head of EL AL Security, Ben-Gurion International Airport, Israel

Last year in Toronto, undercover private investigators wearing hidden cameras entered a local health clinic they suspected was at the center of a long-running insurance fraud scheme.

The investigators had been hired by insurance company Aviva after the company was tipped off by one of its clients.

The undercover operatives posed as accident victims seeking advice, and the clinic staff were more than happy to oblige.

The damning video shows staff members coaching the PIs on how to play up phony injuries, and signing a bogus attendance log for future appointments that would never be fulfilled.

Thanks to the video, the Toronto police moved swiftly to shut the fraudulent operation down—but far too late to protect the insurer from losing untold thousands to past false claims.

What if there were a way to find the fraudsters before they struck?

Today’s police departments have an avid interest in technologies that help them stay ahead of criminals, including analytics-informed strategies for keeping communities safer. But for all the surveillance tech cops deploy on the streets, when it comes to goings-on in the courthouse, they’re practically blind.

Non-Federal court databases aren’t linked under a larger umbrella, which severely curtails law enforcement’s ability to easily locate information on past civil cases. If they don’t happen to know offhand where a case was tried, an officer must visit individual courthouses (or, at best, their online archives) one by one until they get lucky. (This may take time: there are 3,124 circuit courts in the US.)

Litigation analytics for law enforcement is changing that. Premonition’s Vigil system collects information from all of those courthouses into a single searchable database, making it easy to set alerts for case updates, entities and persons of interest. Many aAgencies can now use Vigil to search for insurance fraud red flags like those that might’ve given that Toronto clinic away: plaintiffs who file suit after suit, for example, or witnesses who seem to turn up in case after case.

This technology is so powerful that those searching for a comparison, like Arik Arad above, are forced to bypass real world comparisons—in favor of the science fictional.

Minority Report, and Predicting Crime Before it Happens

Steven Spielberg’s 2002 film Minority Report featured, among other things, spider robots with legs like linguine, two of America’s most acclaimed poets (twins Matthew and Michael Dickman) in mostly nude non-speaking roles and Tom Cruise having his eyeballs removed—yet the most interesting thing about the picture is none of the above. That honor goes to the concept of PreCrime.

In the future, the murder rate has fallen to zero thanks to a trio of psychics or Precogs (including the aforementioned naked poets), who are able to detect murderous intent before it comes to fruition. As in most adaptations from Philip K. Dick’s works (Blade Runner, A Scanner Darkly), this future is hardly utopian, but the idea of preventing crime rather than simply reacting to it remains deeply seductive to law enforcement and the public for obvious reasons.

Like the flying car, crime-predicting psychics will probably remain the express domain of science-fiction for the foreseeable future (no pun intended).

But new technology is allowing police to make certain elements of Minority Report’s PreCrime concept a reality, with all of the attendant possibilities and potential issues.

Do Police Use Analytics to Prevent Crime?

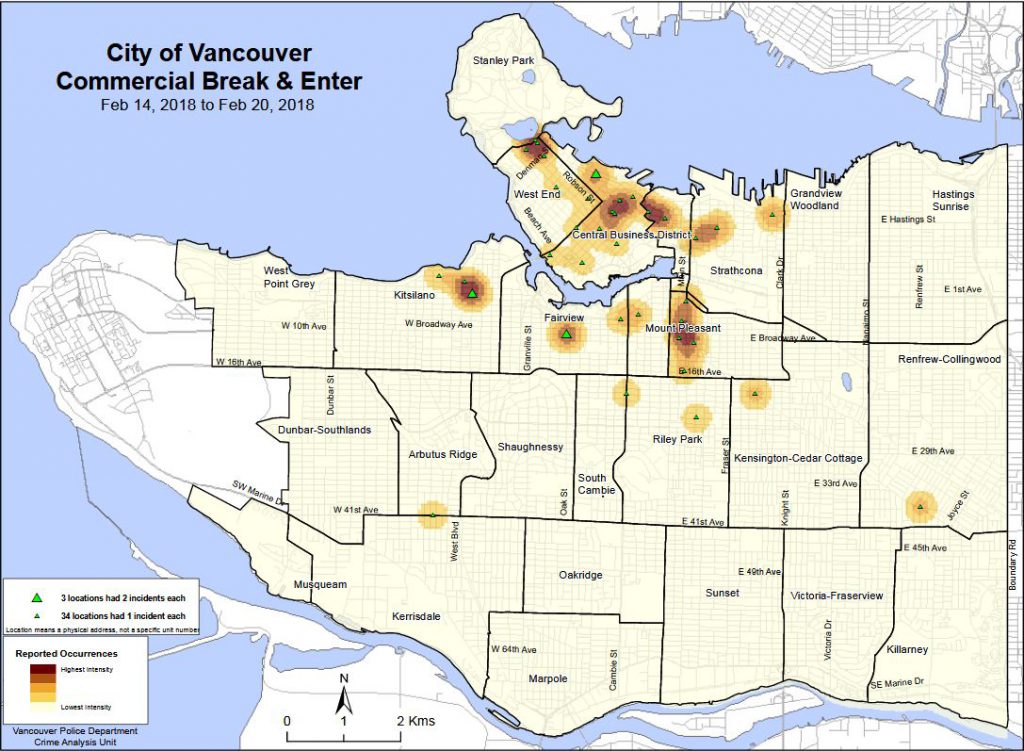

Police have been using analytics-related techniques to manage crime in various cities for decades, most notably the CompStat system developed by former NYPD Commissioner William Bratton and his Deputy Jack Maple. (Click the link to see CompStat in action, with NYC crime statistics broken down by week, month and year.) CompStat began when Maple started simply sticking different colored pins in a map of the city’s transit system to represent different types of crimes and where they were happening; over time, the approach was digitized, extensively augmented, and adopted citywide.

According to the NYPD, since CompStat was instated,

• New York City murders have fallen from 1,946 (five per day) in 1993 to 352 in 2015.

• Other major cities including Los Angeles, Baltimore, Washington D.C. and Vancouver have followed New York’s lead.

• NYC has introduced TrafficStat, which fulfills a similar role but for accidents on the road.

By understanding where crime is concentrated, police can make smarter decisions about where and how to deploy their resources to limit future offenses. This extends beyond posting squad cars on every street corner in a disadvantaged neighborhood. Experts have long recognized crime as a symptom of desperation—those communities where crime is heaviest are also those where the need for social services and economic development is most intense.

Police can and often do use the findings of analytics-esque tools like CompStat to help facilitate bringing help to these neighborhoods. While Minority Report thrills with a sequence where a jetpack-sporting Tom Cruise dive-bombs through a skylight to stop a murder just before it happens, the real face of crime prevention has more to do with identifying patterns that predict offenses.

(There are, it should be noted, a number of concerns about how misuse of CompStat-like programs is negatively affecting policing; see this story for an overview.)

Evidence-Based Policing

These strategies are part of a broader move toward evidence-based policing. Experimental criminologist Lawrence Sherman, often considered to be the founder of the approach, defined it as such in 1998:

Evidence-based policing is the use of the best available research on the outcomes of police work to implement guidelines and evaluate agencies, units, and officers. Put more simply, evidence-based policing uses research to guide practice and evaluate practitioners. It uses the best evidence to shape the best practice. It is a systematic effort to parse out and codify unsystematic “experience” as the basis for police work, refining it by ongoing systematic testing of hypotheses.

Many police departments are justifiably proud of the steps they’ve taken to improve their data collection, and to help citizens improve their access to this information; Canadian cities like Edmonton and Vancouver, for example, have made their crime maps accessible to the public.

If police are genuinely committed to making better strategic decisions by augmenting their information-gathering capacity (and the scale of the investments the forces discussed in this article have made suggests that commitment is real), it’s imperative they apply the same logic to another aspect of the justice system: the courts.

Law Enforcement and Legal Analytics

The science of legal analytics (or litigation analytics) is relatively new, but it has advanced rapidly over the past few years. Just as the concept of evidence-based policing was initially influenced by the development of evidence-based medicine, litigation analytics benefits from breakthroughs established in other fields: from the behavioral profiling of human resources analytics, to the web scraping (or crawling) techniques pioneered by the likes of Google to facilitate search, retrieval and analysis.

Premonition uses web crawlers to progressively scrape information added over time to courthouse archives, adding the information to its own constantly-updated database of litigation records. The firm’s database is recognized as the world’s largest, encompassing millions of cases. The company employs an artificial intelligence to sort the cases so that they are easily searchable by:

• plaintiff

• defendant

• judge

• lawyer

• jurisdiction and more.

This eliminates the need for detectives to schlep from courthouse to courthouse to track down the results of civil cases. It also makes it easy to keep up to date on what a person of interest is up to in the courtroom; by setting an alert for new records involving a given name, it’s easier for police to “follow the money,” or to confirm a suspect’s background.

Litigation analytics experts work with law enforcement agencies to identify suspicious activity. As in the insurance fraud example discussed earlier, algorithms can be “taught” to pick out claims that have a higher likelihood of being fraudulent; courtroom records are in the public domain, meaning that police can use these tools during their preliminary investigations without requiring a warrant.

When the NYPD has a CompStat meeting, it looks like this:

Among the Command and Control Center’s high-tech capabilities is its computerized “pin mapping” which displays crime, arrest and quality of life data in a host of visual formats including comparative charts, graphs and tables. Through the use of geographic mapping software and other computer technology, for example, the CompStat database can be accessed and a precinct map depicting virtually any combination of crime and/or arrest locations, crime “hot spots” and other relevant information can be instantly projected on the Center’s large video projection screens.

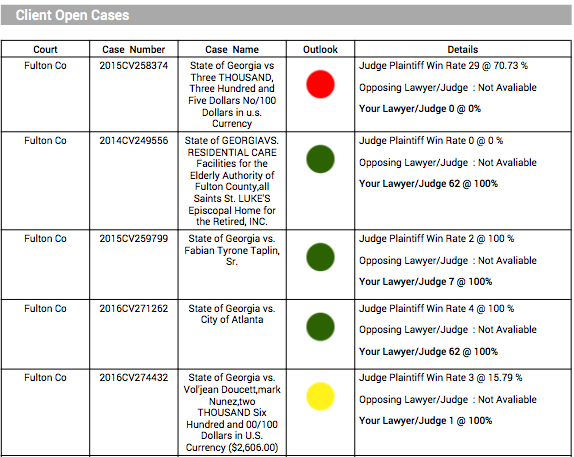

Premonition’s case reports are not dissimilar; they can be used to pull up various charts and graphs depicting key information about past or ongoing cases, and even to make predictions about their outcomes.

Legal Analytics for Prosecutors

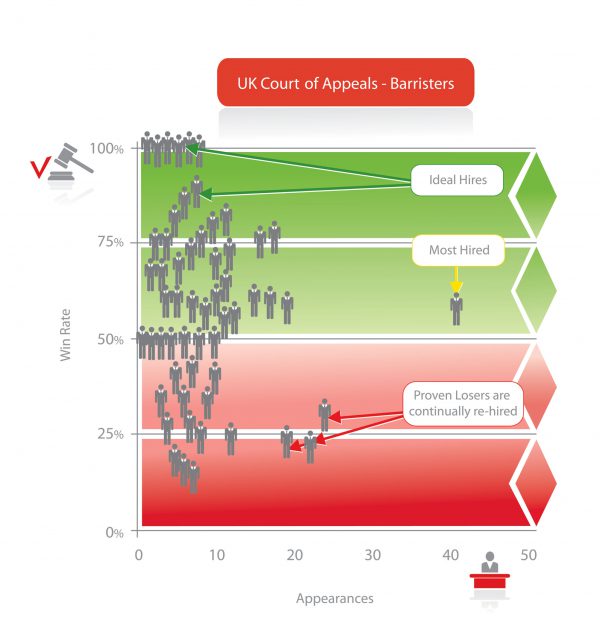

The latter point is of special interest for prosecutors. Choosing whether to press charges, offer plea bargains and pursue appeals is at the district attorney’s discretion. These decisions have important implications for community safety, costs to an overburdened system and even the DA’s own career. Rather than relying on hunches, prosecutors can use litigation analytics to handicap their odds of securing a conviction based on the track record of the judges assigned to their cases and the lawyer for the defense, as well as overall trends for various offenses in their jurisdiction.

Analytics may hold great potential for speeding up the pretrial phase for urban criminal courts, where defendants unable to make bail are often held for weeks or even months before even being formally charged with a crime. By standardizing procedures for less serious crimes and thereby reducing wait times, prosecutors can use analytics to lessen the impact of detention on vulnerable populations.

Predicting the Future of Law Enforcement

Already, virtually no aspect of society is free of the influence of big data, and it doesn’t take a state of the art artificial intelligence to predict that law enforcement will be no different. It’s up to leaders in the law enforcement community to recognize that implementing these techniques is a major challenge which offers great potential benefits.

Analytics will not replace the wisdom of judges, the creativity of lawyers or the instincts of investigators, nor will it free the public from the responsibility to hold its protectors accountable. But it does offer the possibility of a safer and more efficiently-managed future, and greater justice for all.