Rise of the Robolawyers

Rise of the Robolawyers

How legal representation could come to resemble TurboTax

Near the end of Shakespeare’s Henry VI, Part 2, Dick the Butcher offers a simple plan to create chaos and help his band of outsiders ascend to the throne: “Let’s kill all the lawyers.” Though far from the Bard’s most beautiful turn of phrase, it is nonetheless one of his most enduring. All these years later, the law is still America’s most hated profession and one of the least trusted, whether you go by scientific studies or informal opinion polls.

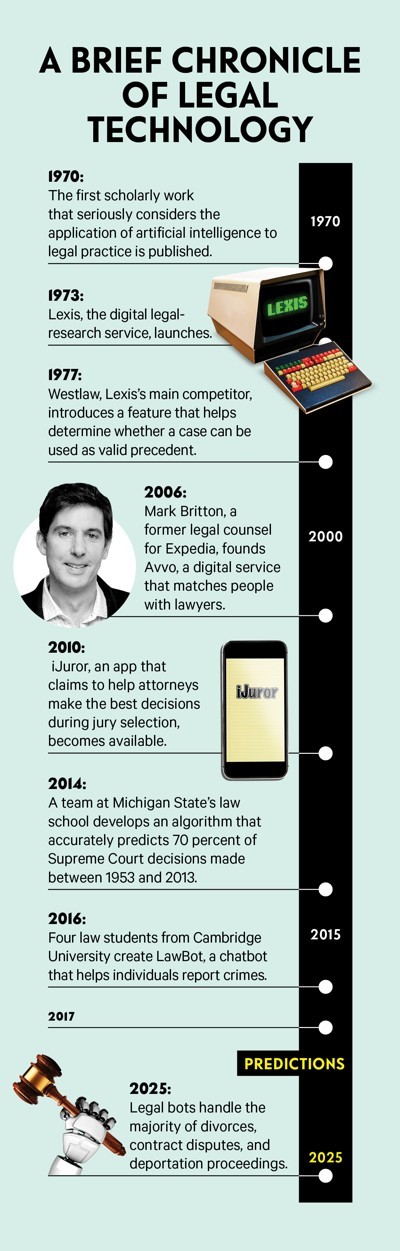

Thankfully, no one’s out there systematically murdering lawyers. But advances in artificial intelligence may diminish their role in the legal system or even, in some cases, replace them altogether. Here’s what we stand to gain—and what we should fear—from these technologies.

Handicapping Lawsuits

For years, artificial intelligence has been automating tasks—like combing through mountains of legal documents and highlighting keywords—that were once rites of passage for junior attorneys. The bots may soon function as quasi-employees. In the past year, more than 10 major law firms have “hired” Ross, a robotic attorney powered in part by IBM’s Watson artificial intelligence, to perform legal research. Ross is designed to approximate the experience of working with a human lawyer: It can understand questions asked in normal English and provide specific, analytic answers.

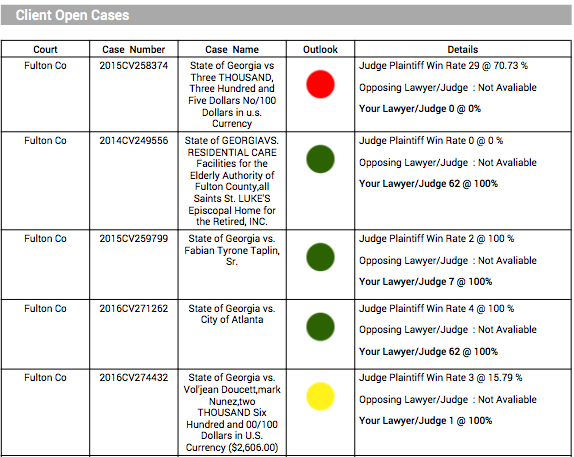

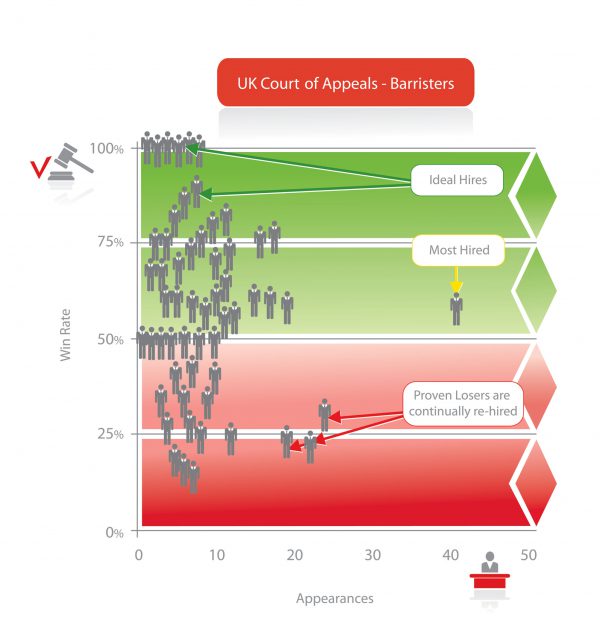

Beyond helping prepare cases, AI could also predict how they’ll hold up in court. Lex Machina, a company owned by LexisNexis, offers what it calls “moneyball lawyering.” It applies natural-language processing to millions of court decisions to find trends that can be used to a law firm’s advantage. For instance, the software can determine which judges tend to favor plaintiffs, summarize the legal strategies of opposing lawyers based on their case histories, and determine the arguments most likely to convince specific judges. A Miami-based company called Premonition goes one step further and promises to predict the winner of a case before it even goes to court, based on statistical analyses of verdicts in similar cases. “Which attorneys win before which judges? Premonition knows,” the company says.

If you can predict the winners and losers of court cases, why not bet on them? A Silicon Valley start-up called Legalist offers “commercial litigation financing,” meaning it will pay a lawsuit’s fees and expenses if its algorithm determines that you have a good chance of winning, in exchange for a portion of any judgment in your favor. Critics fear that AI will be used to game the legal system by third-party investors hoping to make a buck.

Chatbot Lawyers

Technologies like Ross and Lex Machina are intended to assist lawyers, but AI has also begun to replace them—at least in very straightforward areas of law. The most successful robolawyer yet was developed by a British teenager named Joshua Browder. Called DoNotPay, it’s a free parking-ticket-fighting chatbot that asks a series of questions about your case—Were the signs clearly marked? Were you parked illegally because of a medical emergency?—and generates a letter that can be filed with the appropriate agency. So far, the bot has helped more than 215,000 people beat traffic and parking tickets in London, New York, and Seattle. Browder recently added new functions—DoNotPay can now help people demand compensation from airlines for delayed flights and file paperwork for government housing assistance—and more are on the way.

DoNotPay is just the beginning. Until we see a major, society-changing breakthrough in artificial intelligence, robolawyers won’t dispute the finer points of copyright law or write elegant legal briefs. But chatbots could be very useful in certain types of law. Deportation, bankruptcy, and divorce disputes, for instance, typically require navigating lengthy and confusing statutes that have been interpreted in thousands of previous decisions. Chatbots could eventually analyze most every possible exception, loophole, and historical case to determine the best path forward.

DoNotPay is just the beginning. Until we see a major, society-changing breakthrough in artificial intelligence, robolawyers won’t dispute the finer points of copyright law or write elegant legal briefs. But chatbots could be very useful in certain types of law. Deportation, bankruptcy, and divorce disputes, for instance, typically require navigating lengthy and confusing statutes that have been interpreted in thousands of previous decisions. Chatbots could eventually analyze most every possible exception, loophole, and historical case to determine the best path forward.

As AI develops, robolawyers could help address the vast unmet legal needs of the poor. Roland Vogl, the executive director of the Stanford Program in Law, Science, and Technology, says bots will become the main entry point into the legal system. “Every legal-aid group has to turn people away because there isn’t time to process all of the cases,” he says. “We’ll see cases that get navigated through an artificially intelligent computer system, and lawyers will only get involved when it’s really necessary.” A good analogy is TurboTax: If your taxes are straightforward, you use TurboTax; if they’re not, you get an accountant. The same will happen with law.

Minority Report

We’ll probably never see a court-appointed robolawyer for a criminal case, but algorithms are changing how judges mete out punishments. In many states, judges use software called compas to help with setting bail and deciding whether to grant parole. The software uses information from a survey with more than 100 questions—covering things like a defendant’s gender, age, criminal history, and personal relationships—to predict whether he or she is a flight risk or likely to re-offend. The use of such software is troubling: Northpointe, the company that created compas, won’t make its algorithm public, which means defense attorneys can’t bring informed challenges against judges’ decisions. And a study by ProPublica found that compas appears to have a strong bias against black defendants.

Forecasting crime based on questionnaires could come to seem quaint. Criminologists are intrigued by the possibility of using genetics to predict criminal behavior, though even studying the subject presents ethical dilemmas. Meanwhile, brain scans are already being used in court to determine which violent criminals are likely to re-offend. We may be headed toward a future when our bodies alone can be used against us in the criminal-justice system—even before we fully understand the biases that could be hiding in these technologies.

An Explosion of Lawsuits

Eventually, we may not need lawyers, judges, or even courtrooms to settle civil disputes. Ronald Collins, a professor at the University of Washington School of Law, has outlined a system for landlord–tenant disagreements. Because in many instances the facts are uncontested—whether you paid your rent on time, whether your landlord fixed the thermostat—and the legal codes are well defined, a good number of cases can be filed, tried, and adjudicated by software. Using an app or a chatbot, each party would complete a questionnaire about the facts of the case and submit digital evidence.

“Rather than hiring a lawyer and having your case sit on a docket for five weeks, you can have an email of adjudication in five minutes,” Collins told me. He believes the execution of wills, contracts, and divorces could likely be automated without significantly changing the outcome in the majority of cases.

There is a possible downside to lowering barriers to legal services, however: a future in which litigious types can dash off a few lawsuits while standing in line for a latte. Paul Ford, a programmer and writer, explores this idea of “nanolaw” in a short science-fiction story published on his website—lawsuits become a daily annoyance, popping up on your phone to be litigated with a few swipes of the finger.

Or we might see a completely automated and ever-present legal system that runs on sensors and pre-agreed-upon contracts. A company called Clause is creating “intelligent contracts” that can detect when a set of prearranged conditions are met (or broken). Though Clause deals primarily with industrial clients, other companies could soon bring the technology to consumers. For example, if you agree with your landlord to keep the temperature in your house between 68 and 72 degrees and you crank the thermostat to 74, an intelligent contract might automatically deduct a penalty from your bank account.

Experts say these contracts will increase in complexity. Perhaps one day, self-driving-car accident disputes will be resolved with checks of the vehicle’s logs and programming. Your grievance against the local pizza joint’s guarantee of a hot delivery in 10 minutes will be checked by a GPS sensor and a smart thermometer. Divorce papers will be prepared when your iPhone detects, through location tracking and text-message scanning, that you’ve been unfaithful. Your will could be executed as soon as your Fitbit detects that you’re dead.

Hey, anything to avoid talking to a lawyer.

Source: The Atlantic