Shopping Smart for Legal Services

Shopping Smart for Legal Services

With some lawyers billing > $1,500 ph, is it possible to get (and measure) value for money?

The market for legal services can be murky one, whether you’re a general counsel for a Fortune 500 company or a regular schlub shopping around for a divorce attorney.

Word of mouth remains the usual method for clients to find representation, but how do you meaningfully compare lawyers when all you have to work with is a (likely questionable) recommendation and an hourly rate?

The economic downturn has pushed down or frozen the rates of many lawyers, with many corporate legal departments finding ways to reduce their reliance on outside firms, but prices for a few highly specialized fields continue to soar. Top attorneys can command prices in excess of $1,500 per hour for their expertise in mergers and acquisitions, tax, restructuring and antitrust cases where millions hang in the balance.

As such, general counsels often report feeling as though their hands are tied when it comes to making these decisions—a critical loss can cast an unflattering light on prior efforts to curb spending on representation.

It’s worth taking a minute to look at the factors that determine how much lawyers cost:

1. Billing method and pricing structure

2. The size and prestige of the law firm

3. The area of law, or the type of legal work being done

4. The experience level of the lawyer

5. The location where the legal services are being performed (Source: LawKick)

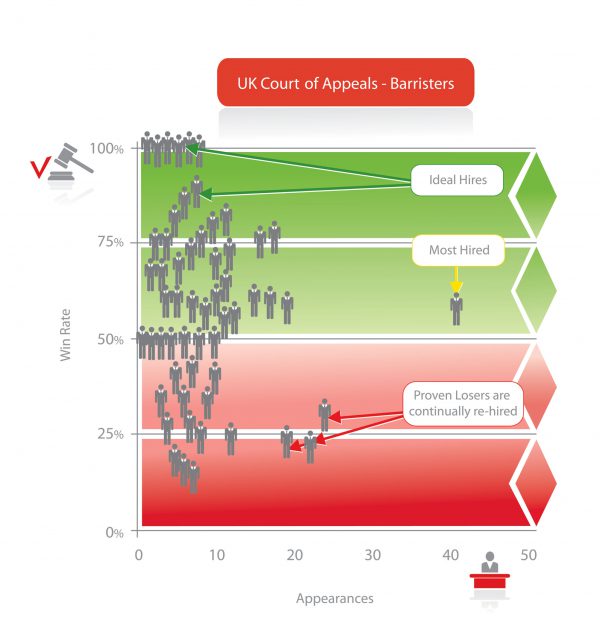

Sharp-eyed readers will note that none of these factors directly address the question of how effective an attorney is at actually winning cases. Yes, prestige and experience suggest a winning pedigree, but they are both clearer indicators of a perception of quality than proof of such. Tom Brady and Jay Cutler, for example, are both “experienced” football players. The reason you’d prefer to have Brady over Cutler as your starting quarterback has little to do with the number of years he’s been in the league. Not only that, but prestige in one practice area doesn’t mean a lawyer’s skills apply to others. Tom Brady may throw a football well, but if he’s playing center on an NBA team he’s going to get dunked on all night.

What’s missing from this equation is, well, equations. To stretch the Brady versus Cutler comparison just one small step further, you don’t have to have watched a single NFL game to know that Brady is better at his job than Cutler because you can look at their statistics: completion percentage, yards per game, touchdowns and, of course, wins. Without these metrics, the outlook becomes murkier: suppose someone who knows nothing about football happens to watch the two go head to head, and on that particular day Cutler’s team steamrolls Brady’s. Maybe Cutler’s played the game of his life; maybe Brady was hurt; maybe factors completely unrelated to either man’s performance determined the outcome. How is the inexpert viewer to know? And, if asked which quarterback they think is better, which name do you think they would say?

Leaving football behind, at last, the flaws in the present system for choosing representatives become clear. If there is no empirical standard for measuring a lawyer’s quality, it’s difficult for even an expert to say definitively which of two attorneys charging the same rate is a better selection for the case at hand. Those on top tend to stay on top, whether they deserve it or not, while clients pay out the nose for an unknown quantity.

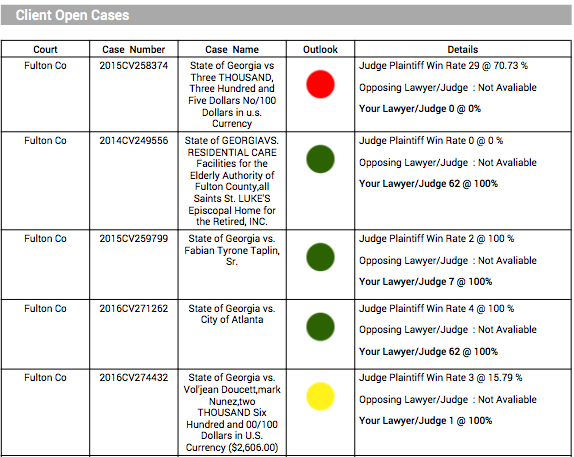

But what would happen if some clients did have access to those missing statistics?

All of the data required to create detailed performance metrics for attorneys is openly available in public courtroom records for anyone to see, as it has been for decades, even centuries. The major impediment has been the sheer volume of information one has to go through to assemble useable metrics. Over the past five to seven years, however, so-called Big Data techniques that rely on machine learning have made it possible to parse vast archives of information in a matter of seconds, and the technology is starting to crossover to the legal industry.

There are however opportunities to start applying analytics to exploit inefficiencies in the market.

By identifying, for example, a litigator with an extremely strong track record who bills significantly less than better-known lawyers in the same field, general counsel have more leverage in negotiating rates—and better odds of getting the best person for the job.

Over time, legal analytics will become part of the standard landscape for finding, assessing and instructing lawyers and the market (including those high rollers) will have to correct and reflect the wide availability of accurate performance statistics.

In the meantime, smart shoppers can access Premonition powered Litigas website, which provides free referrals based on lawyers win rates – it’s a powerful step towards a more transparent way of instructing a lawyer.