What Solo and Small Firms Should Know About Artificial Intelligence

What Solo and Small Firms Should Know About Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is emerging in legal practice, from legal research to predictive analysis. But what is it, and what does it mean for solo and small-firm practitioners?

Feb. 1, 2017 – Here’s the good news: robot lawyers are not taking over, despite emerging applications for artificial intelligence (AI) in the legal sphere. But paying attention to “machine learning” techniques that are developing in the legal industry may reveal new opportunities for competitive advantage, legal technology experts say.

“People are talking about robot lawyers, or robots taking over for lawyers. I don’t think we are anywhere close to that at all,” says Jared Correia, founder and CEO of Boston-based Red Cave Consulting, which provides business management and technology advice to lawyers and law firms. He also co-hosts a podcast called the “Legal Toolkit.”

But Correia notes that AI comes in different forms, and lawyers should be on the lookout for AI developments that might add value to their practices in the near future.

“Companies are developing products that allow lawyers to practice at the top of their law license, that is, to do the very creative things that provide the most value to clients – building strategies, running cases, and figuring out thorny questions of law,” he says.

“The real question is whether AI products will be available to solo and small firms on a useable scale, and whether attorneys will be able to identify the value,” Correia says.

Correia says the form of AI that is currently evolving in the legal industry is commonly known as “machine learning,” a subset of AI that allows users to automate rote processes or structure large data sets through algorithms that can learn over time.

While large law firms are currently testing and exploring these emerging applications in law, Correia hopes AI will eventually become usable and cost-effective for solo and small firm attorneys. “This is where the future is headed,” he says.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The terms “artificial intelligence” and “machine learning” are often used interchangeably, but it may be more accurate to consider machine learning as a subset of, or a precursor to, artificial intelligence. “Cognitive computing” and “intelligent automation” are also used to describe this technology, which took the legal world by storm recently but is not new.

A group of scientists first began studying “artificial intelligence” in the 1950s. The goal was to begin research on the computer simulation of human thinking – to create computer algorithms that mimic the processes our brains use to synthesize information.

To this day, however, modern AI algorithms “have been unable to replicate most human intellectual abilities.”1 Cognitive thinking, especially the abstract reasoning and critical analysis that lawyers do, creates significant challenges for computer scientists.

But as one commentator notes, “AI technology can still have an impact even given the technological inability to match human-level reasoning.”2 That is, machine learning techniques don’t require a simulation of human cognition. Data is all that’s needed.

Consider language translation. The Google Translate application allows users to input a phrase and obtain a relatively if not highly accurate translation in a different language. The computer doesn’t “know” different languages, but the translation is still possible.

“[T]he algorithms that produce the automated translations do not have any deep conception of the words that they are translating, nor are they programmed to understand the meaning and context of the language in the way a human translator might,” wrote Colorado Law School Professor Harry Surden in a 2014 article.

“Rather, these algorithms are able to use statistical proxies extracted from large amounts of previously translated documents to produce useful translations without actually engaging in the deeper substance of the language,” Surden wrote.

The same is true for algorithms that detect spam email. As more data points become available, algorithms can begin to identify the common threads or patterns of spam: key words, country of origin, or whether you have previously corresponded with the sender.

A human can understand a spam email’s context and substance to make the spam classification, but that process would be time-consuming: the algorithm can do it instantly through detection of patterns and correlations within the email data.

And as more data becomes available, experts can teach the computer to interpret the data as new patterns and commonalities emerge. That is, the algorithm can be taught to institute rules, cluster patterns, and organize massive amounts of unstructured data.

This is happening in the medical field, where machines analyze vast amounts of medical data to uncover what a doctor might miss. “Artificial intelligence – essentially the complex algorithms that analyze this data – can be a tool to take full advantage of electronic medical records, transforming them from mere e-filing cabinets into full-fledged doctors’ aides that can deliver clinically relevant, high-quality data in real time.”

Machine Learning in Law Practice

Think about the various tasks that lawyers perform, and how machine learning could play a part. From legal research to contract drafting, from e-discovery to predictive analysis, machine learning could use legal data to inform the work of lawyers.

And that’s already happening. ROSS Intelligence, powered by IBM’s Watson (the supercomputer that won Jeopardy) is being used to automate basic legal research.

“ROSS will do the basic research tasks for you,” Correia said. “My assumption is that it works with basic level searches and gets you to a point where you have a research trail. Then you can dive in later on and do more complex searches.”

A recent article from Law.com described a ROSS demonstration at Milwaukee-based von Briesen & Roper S.C., one of a number of large law firms currently using ROSS for bankruptcy law research. A VP of strategic partnerships at ROSS typed a question: “When can student loans be discharged in bankruptcy in Arizona?”

“The system retrieved passages from several rulings that most nearly summarized their holdings,” noted Law.com’s Susan Beck. “The results showed that courts use a three-part test that looks at whether the loan has become an undue hardship.”

William Caraher, chief information officer at Von Briesen – and a 2016 recipient of the State Bar’s Wisconsin Legal Innovator award – told Law.com that ROSS seems to produce better results than a traditional legal research platform that requires keyword or Boolean searches for best results, despite a natural language option.

A benchmark report, as noted by legal tech blogger Robert Ambrogi, found that ROSS “outperforms Westlaw and Lexis Nexis in finding relevant authorities, in user satisfaction and confidence, and in research efficiency, and is virtually certain to deliver a positive return on investment.” But a follow-up reporting noted ROSS’s current limitations.

A principal analyst that helped benchmark ROSS as an effective product indicated that ROSS “only provides options for specialized research areas (such as bankruptcy), which means assessing it as a replacement for Westlaw or Lexis is premature.”

And Beck’s article notes that both Thomson Reuters (which owns Westlaw) and LexisNexis have been “integrating aspects of artificial intelligence into their products for years (although not using Watson), and have more powerful products on the horizon.”

Fastcase, which partners with the State Bar of Wisconsin to provide online legal research as a member benefit, added “Bad Law Bot” as an Authority Check feature in 2013. It uses AI algorithms to find negative citation history “then flags those cases that have negative citation history and provides you with links to those cases.”

“The flags you see in Lexis and Westlaw are generated by attorneys they hire to determine whether a case is good or bad law,” Correia says. “Bad Law Bot uses algorithms for that, allowing them to save costs and compete with other companies.”

Other AI Applications

While legal research is a major area of AI innovation, machine learning and other forms of AI are emerging, including predictive coding, which “uses natural language and machine learning techniques against the gigantic data sets of e-discovery.”

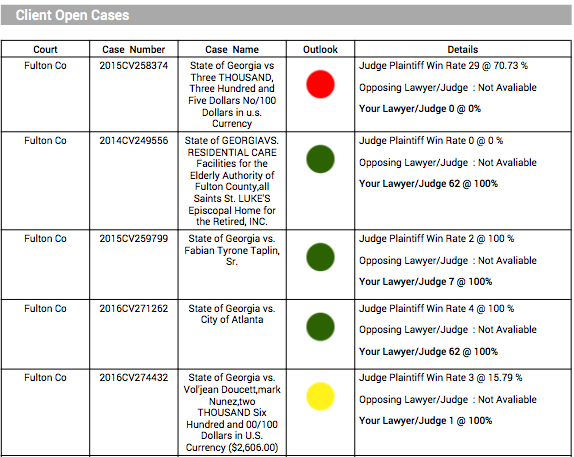

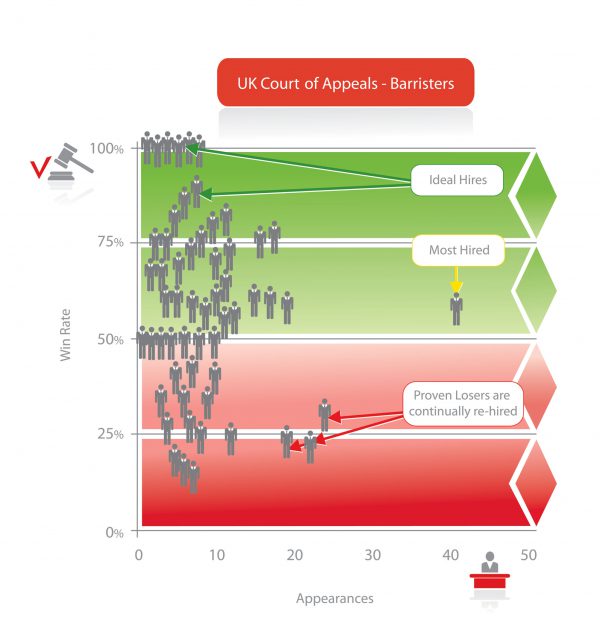

Other companies are focused on predictive outcomes. Premonition mines data to “find out which attorneys win before which judges.” Lex Machina “mines litigation data, revealing insights never before available about judges, lawyers, parties, and the subjects of the cases themselves, culled from millions of pages of litigation information.”

Neota Logic uses AI to power expert systems that help companies manage compliance with laws and regulations. Other companies use AI to help manage contracts – from contract review to contract drafting, from contract classification to contract interpretation.

Harry Surden, the law professor in Colorado, said attorneys could potentially use machine learning to “highlight useful unknown information that exists within their current data but which is obscured due to complexity,” such as the probability of an early settlement when the defendant is a hospital compared with other defendants.

“This is the type of relationship that a machine learning algorithm might detect, and which may be relevant to legal practice, but might be subtle enough that it might escape notice absent data analysis,” Surden wrote in his 2014 article.

Forecasting the AI Impact

Tison Rhine, the practice management advisor for Practice 411™ – the State Bar of Wisconsin’s Law Office Management Assistance Program – agrees that AI will play a role in driving efficiencies in law practice and law office management. But he notes that the verdict is still out on how AI will impact traditional legal business models.

“AI is still in the nascent stages, especially in its applications to law practice,” Rhine says. “For many lawyers, it may take some time to see the value in what is described as AI, things like machine learning, cognitive computing, and natural language processing.”

Rhine says that when lawyers do see the value in AI products, they may be tempted to use them to churn out high volumes of simple legal tasks in an effort to compete with low-cost alternatives, especially bread and butter legal products they have always provided.

“Thinking about how tax software – software that is not even AI – has impacted the accounting industry, this may be a competition that most attorneys can’t win,” he says. “But truly intelligent AI, which does not require humans to supply the context necessary for critical thinking and problem solving, still appears to be quite distant in our future.”

For now, Rhine says, human lawyers should think of AI processes as high-value helpers, not the competition.

Conclusion

According to both Correia and Rhine, there is no doubt that AI will continue to infiltrate the legal sphere and AI tools will increasingly allow lawyers to practice law at a higher level in the near future. But solo and small-firm lawyers may be slower to adopt it.

“In 10 years from now, we will probably see 15 or 20 percent of solo and small firms using AI, which is about the adoption I’ve seen for case management software over the last decade,” says Correia, a former law practice management advisor for the state of Massachusetts. “Change will happen once lawyers start to see their competitors effectively using AI and billing more for higher-level services.”

“Time will tell,” says Rhine. “Either way, whether through adoption or adaptation, lawyers in all types of practice settings should be prepared for it. AI and the improved and alternative legal services it will enable, is happening.”

Source: wisbar.org