“If I Had Asked People What They Wanted, They Would Have Said Faster Horses”: Specialty Courts & Hope for Innovative Attorneys

Originally Published: Michigan State Legal Forum. . Author, Jay Lonick

In the past five years, prospective lawyers have endured a “non-stop litany of negative stories about the dismal job market.”[1]Doubts and speculation about the viability of investing in a legal education, however, have led to significant improvements in efficiency and profitability. One of the newest shifts has been the pressure for lawyers to specialize in fields of practice to encourage expertise and more predictable client outcomes. In response, lawyers should expect more state legislatures to recognize this trend by supporting the specialization of the places where lawyers do business: the courts. My purpose in this post is to use Michigan’s specialized business courts as an example of how soon-to-be attorneys can benefit from innovation aimed at the judiciary. In part two of this post, Clint Westbrook provides an example of private-sector change in the legal marketplace to show how the trend toward using data, lean thinking, and predictive legal practice is already underway.

In 2012, Michigan took a major step toward greater legal efficiency and predictability by passing the The Michigan Business Court Act (MBCA). Chapter 80 defines a “business or commercial dispute” as any action in which all parties are business enterprises, or an action where at least one party is a business and the other parties are past or present owners, managers, or shareholders (and a variety of similar relationships). Second,

“commercial disputes” under the MBCA involve claims arising out of information technology, internal affairs of businesses and the rights of participants, and actions “arising out of contractual agreements or other business dealings.” Further, § 8035 requires that the dispute have an amount in controversy over $25,000, a relatively low bar. The MBCA doesn’t clarify whether a party must be a “business enterprise” and claim a “commercial dispute,” so potential for case overload is possible. However, results so far have been positive.

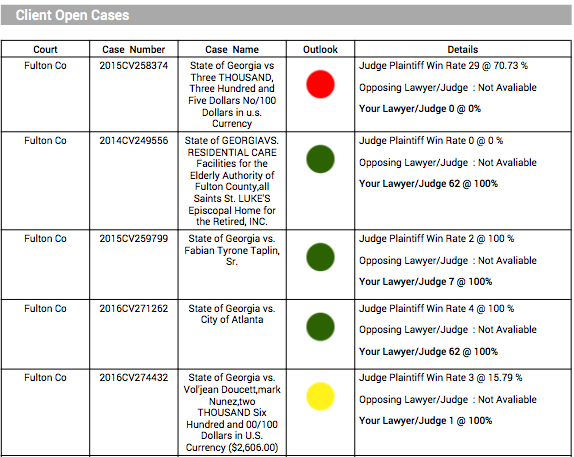

Detroit attorney Jason Shinn stated that “the common focus businesses will find is on early settlement” due in part to the more data that business courts provide, which encourages cost-effective resolution.[2] One option parties have is the “Business Related Opinions Look Up” option, which allows users to search keywords in cases a particular “business judge” has decided. In addition, the MBCA also requires eFiling and online publication of decisions, allowing case analysis to improve at the outset because data serves as a tool for lawyers to assess the viability of claims and defenses. Early results show the business court transition has been smooth based on its efficient case management. In 2013, 2,012 cases were filed in business courts in Kent, Macomb, Oakland, and Wayne counties. Of those, 1,049 were closed and the average time for case resolution was 118 days.

A main goal of the MBCA was to provide the judiciary greater access to technology, a problem that made dealing with courts inefficient in the past. Michigan is not alone: according to the National Center for State Courts, twenty-two states have adopted some form of specialty “business courts” to resolve commercial disputes and internal management and control issues. In evaluating the future of business courts, it would be remiss to not discuss Delaware, which is well recognized as the leader in business-court evolution. In 2010, Delaware also expanded its Chancery Court jurisdiction—which for 200 years had focused on mostly equitable issues—to commercial and technology-based claims when the court created its “Complex Commercial Litigation Docket.” Furthermore, Hong Kong, Saudi Arabia, France, Thailand, Turkey, and dozens of other countries have used business courts for many years. It appears that this trend is not isolated; it shows economic awareness and a response to the growing disapproval for uncertain results in the courtroom. As a result, there is likely to be a demand for tech-savvy lawyers who can capitalize on this trend.

Law school may not be the safe career bet it once was, but that doesn’t mean all value is lost. Like a stock that has fallen drastically, at a certain point, it becomes undervalued and worth investing in again. Some have suggested that law school is near the point of reinvestment. However, attending law school at a time when schools are beginning to compete for students is missing the point. The real key for new lawyers is in understanding how to navigate the new legal landscape.

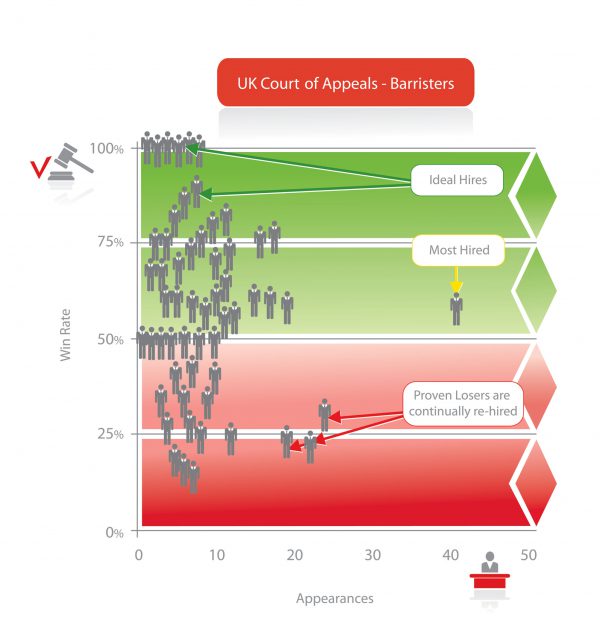

One example of this change is the growth in legal businesses that are dedicated to predictive analytics of win rates, trends and biases, and other statistics to create “a very, very unfair advantage in litigation.”[3] PremonitionLaw, a rapidly growing litigation database is one of those businesses. Dan Kinnear, an advisor and board member at Premonition described the consequences of BigData and decision-making in the practice of law. Kinnear tweeted: “Sometime pretty soon, it won’t be enough to say ‘I think’ without also saying ‘The data indicates and I think.’ Modern law means data.” If Kinnear is right, more lawyers will gravitate toward the use of predictive analytics, and the courts will adjust too.

Business courts provide an example where the courts appear to be ahead of—or at least alongside—the curve. Therefore, new attorneys must learn to leverage data because the legal industry appears to be trending up, but only for those who invest in skills that build cars while many others are still trying to find “faster horses.”

[1] Gary Munneke, Race to the Finish Line: Legal Education, Jobs and the Stuff Dreams are Made of, 84-FEB N.Y. St. B. J. 10 (2012).

[2] Jason Shinn, Michigan Experiments with Business Courts, Mich. Employment Law Advisor (Aug. 20, 2014) (describing his experience in the Metro Detroit Business Courts on non-compete, breach of contract, and other disputes).

[3] See @dkinnear, Twitter, (Mar. 17, 2015).