Why Is Legal Technology So Bad?

Why Is Legal Technology So Bad?

“That’s a great idea, it will save Attorneys hours every case and save several thousand dollars for the clients. No one will buy it.”

“What do you mean no one will buy it?”

“Attorneys get paid by the hour, if you save them time, you cost them money. They’ll never buy it. They’ll say they’re interested and might buy if you can make a few changes, but they’ll never buy. If you want them to use that system, you’ll have to get the Courts to mandate it.”

The legal tech entrepreneur I was talking to paused, then told me he hadn’t made a single sale. He called me back 2 weeks later to thank me. He’d done a press release aimed at the Courthouses and had just had an enquiry from the Canadian Court system. His idea to automate document production and deposition scheduling was a good one. It just needed a receptive audience, and law firms weren’t it.

What other industry is there where becoming more efficient actually costs money?

Where innovation is actually disincentivized?

Is this the only reason legal tech is so backward?

More importantly, what can we do about it?

Legal technology has the lowest venture capital investment rate of any industry. Legal technology is at least 15 years behind the technology industry in general. Last week, during our marathon slog of cataloguing every Courthouse in America, we found a Courthouse in Georgia where the Clerk posts schedules on their website in WordPerfect format. You cannot make this stuff up. Documents prepared in software that was obsolete 20 years ago—a format practically no one can read and practically no effort needed to change to Word—yet this antiquated nonsense has lingered since the last century.

Data

There are fifteen million civil lawsuits filed in America—41,000 a day. America has 95% of the world’s litigation stemming from only 5% of the world’s population. America, being essentially the only democracy to lack a “loser pays” rule, means there is essentially no downside to bringing cases with little or no merit. For plaintiff’s counsel, the courts are like casinos where, if you lose, you’re only out your time. The one and only upside from this disgraceful scenario is that there is an awful lot of data to analyze.

The problem is that it’s not in one place. The Federal system has less than 2% of litigation, and, though a reasonable number of states have integrated court systems, the norm is a county-by-county arrangement and none of the states are linked. One could be forgiven for thinking it was a Government operation. The major legal publishers have focused traditionally on appeals cases. The problem is that these represent less than 1% of litigation. 97% of cases rest at the circuit and county level and have been essentially ignored by the major publishers.

Why? “Federal courts were easy. State courts were not,” said Amy Hrehovcik in “10 Things I Learned While Falling in Love with “Big” Data.”1 She details her time at Thomson Reuters attempting to acquire state court data. Someone would print out some case data, schlep it to the other side of the courthouse, where someone else would scan it back in again, enter some fields manually, and then upload it to their database. They’d measure it with stop watches to get it “efficient” though. It’s a huge amount of effort to do across the country 41,000 times a day. Not surprisingly, they couldn’t get anywhere close to a national system. Our Artificial intelligence can handle the same activity in less than a second, whilst reading and understanding the case, too.

Automation and machine learning are why a start up from nowhere has been able to cover over 70% of US free cases in less than a year. With data comes transparency, and transparency, as we shall see, is where every positive change in law will begin.

Buyers Aren’t Users

The purchaser of legal technology is rarely the person who actually uses it. Why is this a problem? Imagine you’re going to buy someone his or her first car. You might buy them a 5-year-old Honda. It’s affordable, reliable, and meets travel needs. It won’t go from 0 to 60 in 3.2 seconds or get parked next to the valet stand, but it’s all they need. Now, imagine it’s a car for you to drive, too. You’ll likely buy a Mercedes. It will be new and come with a warranty. You’re going to be the one using it, so the soft factors—and all of the small details that make driving a Mercedes great—come into play.

Ravel Law has recently come out with a new citation system. It’s pretty and clever, likely the best one on the market. The “Mercedes” of citation systems. If I were doing legal research, it’s what I’d want to use. I wonder if it will be a big seller though. LexisNexis and Westlaw have marketing clout that’s hard to beat. As “no one got fired for buying IBM,” buying their citation systems is a safe, conservative move. Law firms are all about safety and conservatism. If you don’t have to use the system yourself, the fact that it may be nicer to use is irrelevant. Users don’t decide, and decision makers don’t use. Why bother innovating if there’s no incentive to? If you’ve used citations systems, this is painfully obvious. They’re basically 1980s technology. Terrible and expensive. Why? Because they can be. Where are clients going to go?

The Hourly Rate

If there’s one thing that’s been picked to death in law, it’s the hourly rate. Its demise has been predicted for decades, yet still it lingers like the last guest at a party. What’s the point of being efficient if your opponent is paid to drag things out? There’s the age-old argument that you don’t know what’s going to happen in litigation, so you can’t really estimate the costs. This is a lie we tell ourselves. Let’s take a look at an average civil lawsuit billing.

The client visits a lawyer. The lawyer assures the client they know what they’re doing. The lawyer says the case should be finished for around $25,000 and takes this as a retainer. Then, he spends the next 40 minutes issue spotting to the client’s irritation. Over the next month or so the $25K retainer is depleted rapidly. The client worries it may run out and calls the attorney to ask. “Don’t worry, the beginning is the expensive bit, where we do the most work,” the client is told. A few weeks later, the lawyer calls the client 1 http://premonition.ai/10-things-i-learned-while-falling-in-love-with-big-data/ and tells him that he misrepresented the complexities of the case and that it will actually be closer to $50,000 in total cost. The client is, obviously, annoyed, but realizes that swapping attorneys will lose his sunk costs of getting the lawyer knowledgeable on the case. So, he sends over another $25,000, which is chewed up by frivolous back-and-forth motions, accomplishing little.

At the $50,000 mark, the client receives another request for funds to “get through depositions”. “Don’t worry, we’re almost at the winning line,” he’s told. He grudgingly parts with another $30,000 “to finish the case.” The case actually finishes $20,000 after that at $100,000. If he “wins”, there’s a good chance he won’t be able to collect enough to pay his legal bills, and, if he’s the defendant, he won’t get his legal fees back.

Is the lawyer not aware the case is likely to run to $100,000 when he quotes $25,000? After all, he’s done dozens before. Of course he is. Is he merely being optimistic? No, he’s lying. Why? Because he has to. If he doesn’t, the client will go to an attorney down the street who tells him what he wants to hear. It’s a race to the bottom. One could argue the client is being naive and gets what he deserves. Most clients are unsophisticated purchasers of legal services. Even General Counsel, themselves former litigators, are woefully ignorant of likely costs and outcomes. Our United Kingdom litigation study, the country’s largest ever, found that corporate selection of law firms was 18% worse than random. Why do people make such bad choices in hiring and managing attorneys? Because they lack the data. They lack transparency.

Transparency

I have stated before that every major change for the good in law will come from transparency. Peter Diamandis said, “Most evil is done in the dark.” People do bad things, deliver bad service, break their promises for one reason and one reason only: they can get away with it. No one sees and no one notices. Imagine the same scenario where there is a sign in front of the lawyer’s office saying, “Lawsuit: $100,000.” He can’t claim it’s only $25,000 anymore. If the same sign sits outside his competitors’ offices, then they can’t lie anymore, so now he doesn’t have to either. The client goes into the lawsuit with his eyes open or maybe he decides it’s not worth it and gets on with his life.

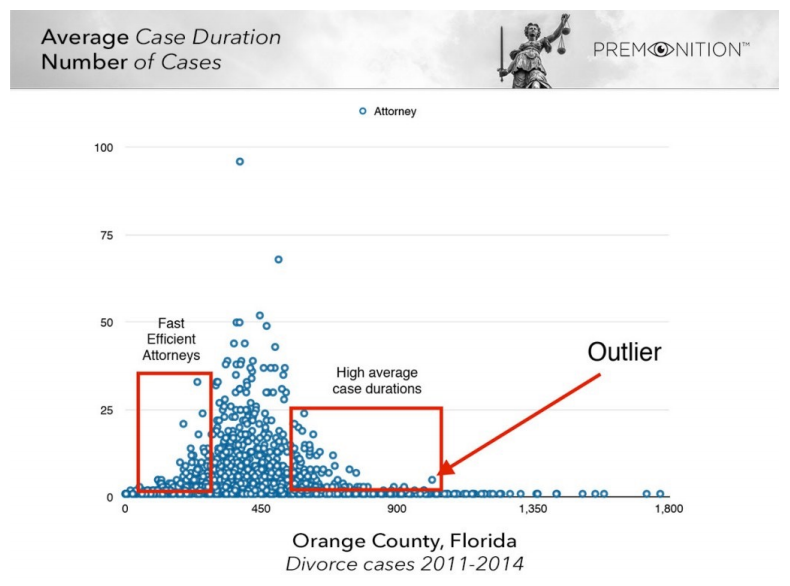

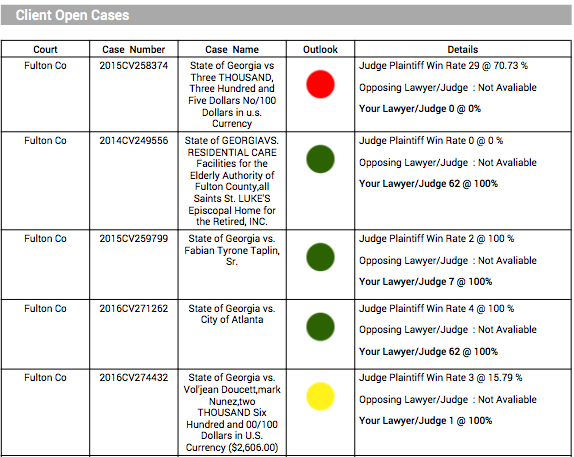

Let’s add to the sign. Take a look at the chart below.

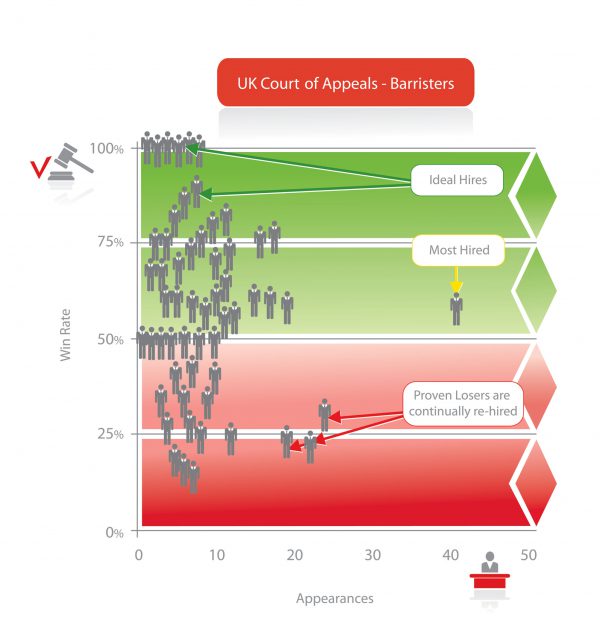

Imagine the outlier on this chart has “Average case duration: 1,000+ days” on his sign. How many people will use him? None. He can’t repeatedly take advantage of clients because they can finally see him for the clock runner he is. The market becomes efficient; it regulates itself because of performance transparency. How much would you pay for an attorney in the left-hand box? Many consumers would happily pay double the going rate because they’re getting a fast, quality service. For the attorneys who currently “suffer” by limiting their billing and doing a fast job, the increase in the number of clients contacting them, and the increased amounts they’re willing to pay, will more than offset their “losses” from not dragging out litigation.

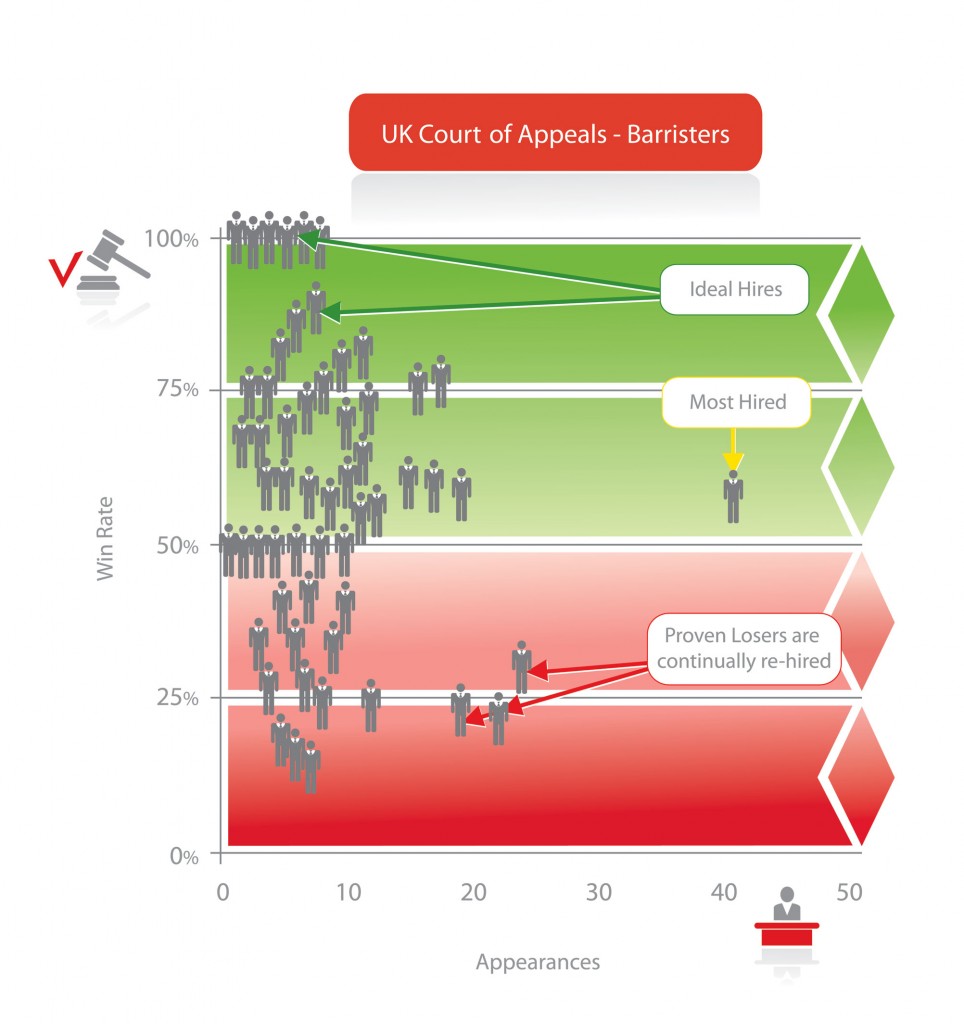

Let’s add one final item to the sign: Performance.

You’re better off representing yourself than hiring the proven losers identified here, because pro se litigants typically average 44% win rates (though your mileage varies significantly from judge to judge). Where does this information lead us?

An Efficient Market

When consumers can compare their litigators by price, case duration, and performance, magical things start to happen.

• The worst performers find something else to do.

• Litigators can’t run the clock anymore.

• Not everyone can be number one, or even top 10. Lawyers that don’t have top win rates can still be competitive. How? By being faster, or cheaper, than their better performing peers. Sixty days quicker might be worth 6% in performance.

Study after study has shown that consumers actually not only prefer flat-fee pricing, but will happily pay more for it. Lawyers offering $120,000 flat-fee litigation—potentially costing $80,000 more if it goes to trial—might actually find themselves not only competitive, but attracting more clients when consumers can see a $25,000 case estimates for the nonsense they are. What’s happened here? The lawyer has just made 20% more money for no extra work. Even more so, he now actually has an incentive to be efficient.

Let’s take this a step further. The attorney who’s just discovered he can make more money by charging flat fees breaks the billing down into stages: $10,000 to onboard and send out/respond to the complaint; $10,000 for document production and setting disposition dates; $10,000 for document review; $20,000 for motions; $30,000 for depositions; then $20,000 for settlement discussions, or $80,000 if it’s going to trial.

Now, he has a serious incentive to be efficient. Let’s say he subcontracts client on boarding to a team in India. Some of the best people in the country research and draft pleadings for $2,000. He puts $8,000 in his pocket and has all the extra hours free to bill another client on another matter. He finds out opposing counsel is also on a flat-fee arrangement. “Let’s use this new service that automatically manages document production and scheduling, it only costs $500 a case,” he suggests. They both make an immediate $9,500 profit and spend the time saved marketing and seeing potential clients. Even if opposing counsel is on the clock, time spent filing motions is going to be less. Why? Because he’s only going to file something if it’s absolutely necessary to the case. Maybe he does the depositions himself, or maybe he sub-contracts them to another attorney in town who specializes in them. It’s likely going to be someone who has the ability to extract the most information in the least amount of time. At the very least, fishing expeditions will stop. Why? They don’t pay. Settlement negotiations are faster because it costs to drag them on. A one-hour settlement is a $20,000 hour. That’s decent money and far surpasses what he’d make on an hourly model.

Now that cases take up much less of his time, he can do more of them. Many more. A model like this scales. He can stamp the process out thousands of times over. Before he was limited to 2,000 to 2,500 hours a year. Now, he has no limit. His earnings aren’t capped, and he has every incentive to be efficient. He can be a little cheaper than his competitors and a little bit faster. This is a rising tide—everyone benefits—and it all starts with transparency.

Finally Technology Can Have A Place in Law

How do you become efficient quickly? The same way as every other industry. Technology and lots of it. Technology to do everything technology can possibly do. You’ve got a bot that can draft a motion? Let’s talk. Software that can transcribe depositions in real-time? Let’s buy a license. Not waiting for a transcript will save me 30 days off my case durations. The eDiscovery document crawlers can now read a deposition transcript and highlight the lies? Let me get my checkbook. Transparency brings about an efficient market, and an efficient market begets efficiency. Efficiency begets good service and fair pricing. Finally, will people stop hating lawyers? Perhaps too much to ask.

By Toby Unwin, Chief Innovation Officer, Premonition LLC

in University of Arkansas at Little Rock, Law Review